Crown Jewels (opened in 1949)

Crown Jewels

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man

in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” – Jane Austen

Jane Austen’s House

Winchester Rd, Chawton, United Kingdom

Jane Austen’s nephew observed of his aunt, “Of events her life was singularly barren, few changes and no great crisis ever broke the smooth current of its course.” Although Jane may have had a seemingly placid existence, she never left England; she nevertheless had her share of sunshine, of storm.

T.G.I.M. (1962)

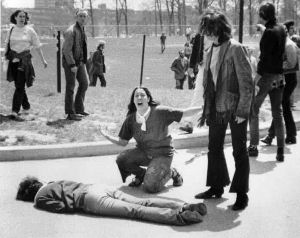

The Kent State Pietá (1970)

The Comedy is Over (1948)

The Italian opera Pagliacci revolves around Canio, the clown; what gives the lie to his smile is his tears over his wife’s adultery. Insane with jealousy, he murders both his faithless partner and her lover. Life imitated art in an Italian soap opera in a crime of fashion.

Anything But (1912)

“I would rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe.” Louisa May Alcott

Orchard House, 399 Lexington Road, Concord Massachusetts.

Some of America’s greatest authors, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau, slumber in Sleepy Hollow, a Concord Cemetery. Another notable grave belongs to the mother of young adult fiction, Louisa May Alcott. If, in Spoon River Anthology fashion, Louisa spoke from the afterlife, her story would involve her family, immortalized in her novel, Little Women..

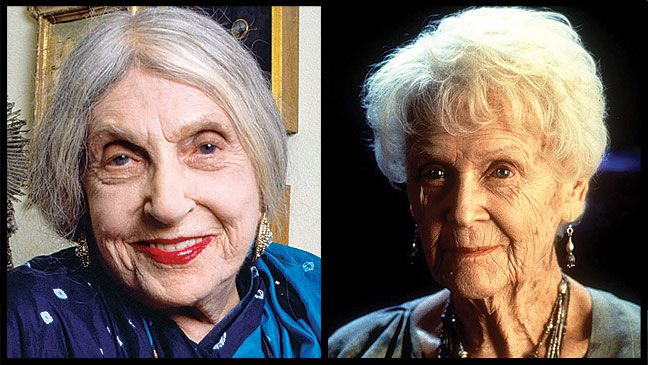

The Next Morning (2005)

“My life is full of mistakes. They’re like pebbles that make a good road.” Beatrice Wood

8585 Ojai-Santa Paula Rd.

Ojai, California 93023

In medieval Florence, Beatrice Portinari served as Dante Alighieri’s guide in his masterpiece, The Divine Comedy. In 20th century California, Beatrice Wood inspired a pivotal character in James Cameron’s blockbuster, Titanic.

A Joy Forever (1766)

.jpeg)

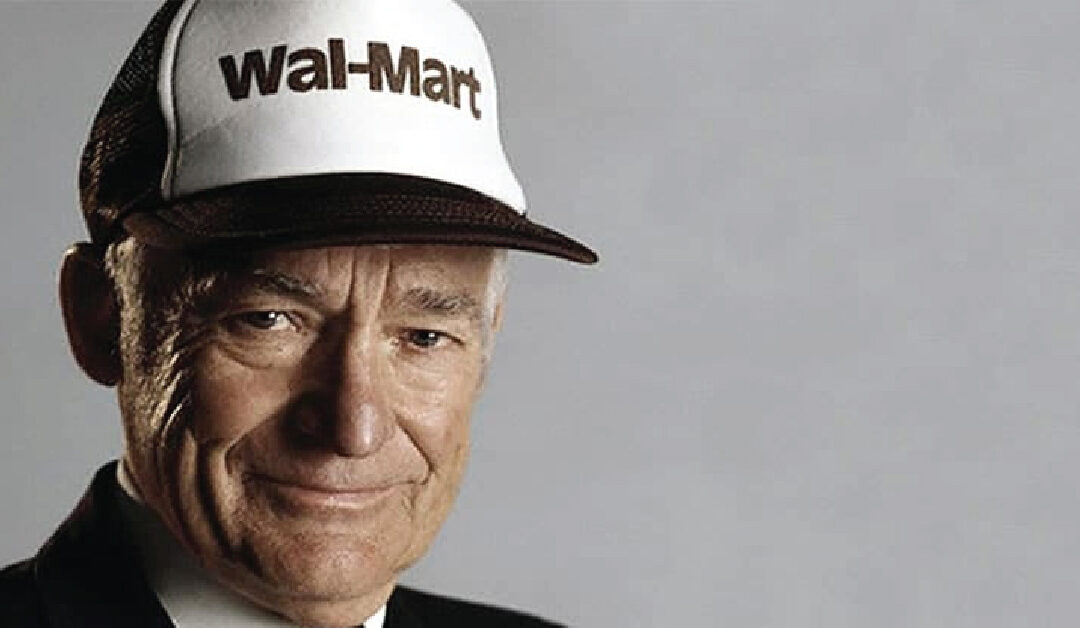

The staccato bark, “Going, going, gone!” followed by the banging of a hammer, signifies the sale of a coveted object to the highest bidder. Christie’s has conducted awe-inspiring auctions, many which would have astounded its founder, James Christie.

Huff and Puff (2005)

The press barons of yore were alpha males whose giant shadows shaped the way the world received its news: Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, Harold Ross. In the 21st century this glass ceiling was shattered by an infusion of estrogen when a Greek Colossus bestrode the shores of media.

Is There Still Sex? (1994)

Before the four female Musketeers of Sex and the City went on the hunt for men, money, and Manolos in Manhattan, there was the real-life party girl, Candace Bushnell, the inspiration for Carrie Bradshaw.

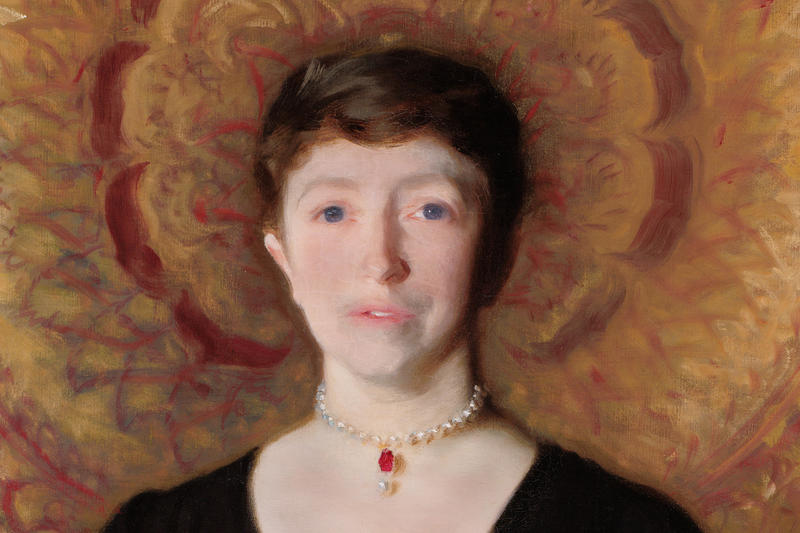

The Truth (1903)

“C’est mon Plaisir” “It is my pleasure.” Isabella Stewart Gardiner

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

25 Evans Way, Boston, Massachusetts

Gods behaving badly is exemplified in Titian’s 16th century painting, “The Rape of Europa.” The canvass reveals Zeus, in the form of a bull, ravishing the maiden. The masterpiece served as the crown jewel in Isabella Gardner’s art gallery, the scene of a violation that involved the art world’s greatest whodunit.

The Female of the Species (1898)

.jpg)

Five Stone Lions (1883)

Doxerl and Johonzel

Tikkun Olam (1980)

Now Abideth Faith, Hope and Love (1912)

Hai-yah! (1974)

The Pink Queen Bee (1963)

America's Sweetheart (1959)

.jpeg)

Moment of a Lifetime (2010)

“And the Oscar for Best Director goes to Victor Fleming for Gone with the Wind; and the Oscar for Best Director goes to John Ford for The Grapes of Wrath; and the Oscar for Best Director goes to Steven Spielberg for Schindler’s List.” The fact that the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences has always gifted the coveted statue to men makes one wonder if there is-to borrow the title of Elia Kazan’s film for which he won best director-a Gentleman’s Agreement. If institutionalized sexism is indeed the norm, the Academy breached it after eight decades when Kathryn Bigelow made a rip in Hollywood’s seemingly shatterproof celluloid ceiling when she won the Academy Award for Best Director. .

Madame Butterfly