Rosebud (1954)

A variation of the 1950s The Adventures of Superman catchphrase is, “Faster than a speeding bullet! More powerful than a locomotive! Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound! Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No-it’s fake news.” William Randolph Hearst was the master of tabloid journalism, but the life of his granddaughter rivaled even his most sensational headlines.

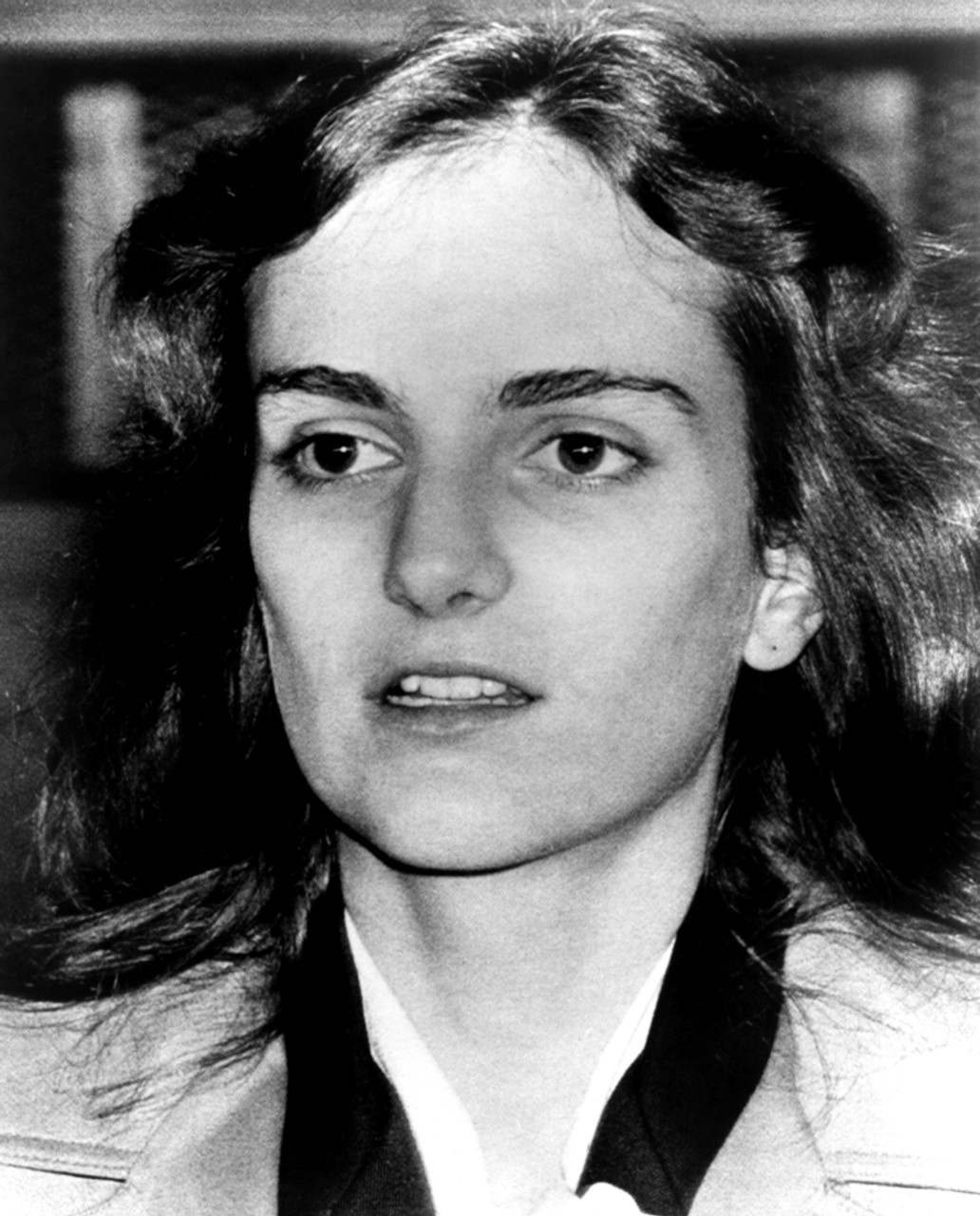

Patricia Campbell Hearst was born the third of five daughters in Hillsborough, San Mateo, one of America’s priciest enclaves. Although the mansion was magnificent, it did not compare to her grandfather’s castle in San Simeon, California’s Versailles, perched atop La Cuesta Encanta, the Enchanted Hill. The heiress attended a series of Catholic schools and, to the dismay of her parents, their beautiful debutante daughter fell in love with her math tutor, Steven Weed. When he left for a graduate position in philosophy at the University of California, (of which her mother was regent), the two moved in together, and Patty enrolled at Berkeley as an art history major. She showed scant interest in the great causes of the day: America’s involvement in Vietnam was crouching its way to an ignominious close, the Watergate scandal that brought Nixon to his knees was swirling through Washington, the Black Panthers were flexing their muscles. Berkeley was a hotbed of student rebellion, but Patty, groomed for a life of luxury and leisure, remained aloof to the radicalism. Her apathy soon underwent a radical metamorphosis.

In February 1974, Steven opened the door to a girl who said she had car problems and needed to use his phone. The next moment two armed men forced their way in, blindfolded Patty, and repeatedly beat her fiancé with a wine bottle. The intruders forced the traumatized teen, clad in a blue housecoat, into the trunk of their car. When the news broke, the press gave it as much attention as they had the Lindbergh baby kidnapping. The amalgam of money and mayhem proved irresistible copy.

The Symbionese Liberation Army, contemporary Robin Hoods who had pledged to steal from the rich to give to the poor, was behind the abduction. The SLA took their name from “symbiosis;” their ideology derived from a mix of black power and Maoism. The disappearance of the Hearst heiress received round-the-clock coverage, but the network news, unsure how to handle a gang of terrorist hippies, made the SLA counterculture superstars by broadcasting every rant about capitalist pigs and imperialist warmongers. To add to this bouillabaisse, the SLA used a communal toothbrush, practiced free love and had as its anthem, “Death to the fascist insect that preys on the life of the people.” Randolph Apperson Hearst, the billionaire editor of The San Francisco Examiner, the cornerstone of his famous father’s newspaper, frantically waited for the amount of his daughter’s ransom.

The kidnapping by the certifiable radicals was sensational enough, but what followed raised the bar on bizarre. The SLA released a tape to the media in which Patty claimed the people she was with were her comrades and fellow soldiers. The recording ended by calling her wealthy parents pigs. In early April another tape bore the message, “I have been given a choice of being released or joining the forces of the Symbionese Liberation Army, and fighting for my freedom and the freedom of all oppressed people. I have chosen to stay and fight.” The heiress made a further announcement where she relinquished her name and was now going by the name Tania in honor of the martyred lover, Tamara “Tania” Bunke, of Che Guevarra. The homegrown terrorists also sent a photograph of Hearst standing in front of a flag of the SLA’s seven-headed cobra insignia.

The Symbionese Liberation Army, in lieu of money, wanted to hold Hearst hostage and swap her for two jailed group members charged with murder-an idea then-Governor Ronald Reagan immediately rejected. They also instructed Patty’s father to fund a multi-million-dollar food program for welfare recipients. Although the family complied, implementation proved to be a disaster. Hearst hired people to distribute cans and produce that they threw from moving trucks that resulted in rioting as people fought over the handouts. The media went into an even greater orgy in April- when Tania got her gun-and participated in an SLA robbery of Hibernia Bank-one owned by the father of her former friend. Patty appeared in the jerky frames of a surveillance video, beret on her head, M1 carbine in hand, shouting demands at terrorized tellers. The photograph became one of the most iconic of the decade. The picture also made the erstwhile sympathetic media change its perspective, and the press-as did the public-thirsted for the rich kid’s blood. A month later, Tania engaged in spraying a Los Angeles sporting goods store with automatic fire as her cohorts robbed the premises. Clues led the police to a house where the group’s core members were hiding; after a two-hour siege, six terrorists were dead. Jubilant LAPD cops joked SLA stood for “So Long Assholes.” For sixteen months, the remaining gang remained on the run, surviving by their wits and petty theft. The police finally arrested Patty in San Francisco after a tip-off. The nation watched with bated breath who would emerge from the fray: Patty the heiress or Tania the radical. The answer came when, before stepping into the police vehicle, the Hearst heiress gave a clenched-fist salute; in custody, she stated her occupation as an urban guerilla.

For the trial- as closely followed as Charles Manson’s that had captivated the country seven years earlier- the Hearst family hired F. Lee Bailey, future star attorney of O. J. Simpson’s Dream Team. He portrayed Patty as a victim rather than as a victimizer and prominent psychiatrists testified that Patty suffered from Stockholm Syndrome. He related when she had first arrived at a Daly City safe house, her captors had locked her in a closet for fifty-seven days and only released her to subject her to rape and indoctrination. The defendant swore she could no more have escaped her captors than a monkey could have escaped its organ grinder. In contrast, the prosecutor painted her as a rebel in search of a cause and had found it with the homegrown hippie terrorists. The country held its collective breath as the jury deliberated whether Hearst was a crime victim or an heiress turncoat.

A popular television series of the 70s was Happy Days, but its name did not presage Patty’s fate. Mainstream America wanted her to pay, and she was more unpopular than the Zodiac Killer who was on the loose. The jury took a day to decide on a verdict of guilty, and the judge meted out a sentence of seven years. Her co-defense attorney later recalled, “She was a victim of a cruel kidnapping. She was a victim of the American people who despised her because she represented the radical nature of young people at the time. She was the victim of the rich, who thought of her as impudent and disrespectful, and a victim of the left and the poor who saw her as a spoiled little rich girl.” The Hearst family was enraged at what they believed was a travesty of justice; her sisters referred to her imprisonment as a second kidnapping. Her supporters felt Patty-except for her name and fortune- had been a typical teenager who had endured five years of torment followed by a three-ring-circus-trial. Like Paul Simon’s Julio, Patty’s image stared back from the cover of Newsweek; in her case, she appeared several times.

At the medium-security prison in Pleasanton, California, the heir to a dinosaur-sized trust fund of twenty-five million dollars worked as a waitress for two cents an hour and, as she quipped, “The tips are lousy.” One of her fellow inmates was Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme of the Manson family infamy though Hearst reserved a dubious slot as the prison’s most celebrated inmate. However, when Squeaky escaped and attempted to assassinate President Gerald Ford, she garnered top prison billing upon recapture. The saga of Patricia Campbell Hearst came to an official close when President Jimmy Carter curtailed her prison sentence after twenty-two months; later President Bill Clinton granted her a full pardon. The two reprieves may have accrued from having a family who could pull powerful strings. The presence of more than a hundred reporters and photographers, armed military police, and a hovering helicopter that gathered at her release testified interest in her had not waned.

Patricia Campbell Hearst has donned many guises: pampered daughter of privilege, Berkeley student, urban guerilla, Pleasanton prisoner; the common denominator amongst all these reincarnations was her ability to survive, a resilience of which Grandfather Hearst would have approved. And what helped her do so post-incarceration was the steadfast support of Bernard Shaw, a divorced former police officer. They had met in 1976 at San Francisco’s Top of the Mark restaurant the day after Hearst departed prison on 1.5 million dollars bail. Shaw was one of twenty bodyguards hired by the Hearst family. After the United States Supreme Court refused to hear her appeal and she had returned to her cell, Shaw drove sixty miles from his home four times a week to visit. On Valentine’s Day in 1978, they were married in a brief but well-publicized Episcopal ceremony at a naval based in San Francisco Bay. Shaw had insisted it take place in a military compound out of fear of kooks. Her parents predicted such a short shelf life for the union they merely gave a Sears vacuum-cleaner for a present. The marriage proved happy, and they had daughters, Gillian and Lydia Hearst-Shaw. Of meeting the woman he called the love of his life, Bernard stated, “I remember I thought she was awfully small. And I thought she was cute. She had a real nice smile.” He also proved her protector, ensuring she wore a bullet-proof vest when she walked from prison a free woman though forever a captive of infamy. Shaw was the opposite of Weed, who, in a nod to his name, had turned on his former girlfriend when the mega-sized s*** hit the fan.

With the passage of forty decades, Patricia Hearst-Shaw has donned another face, one of society matron. The role had almost been derailed-when she became the ultimate girl interrupted. Today the East Coast heiress, with her carefully coiffed highlighted hair, bears little resemblance to the willowy, black-bereted-gun-toting Tania. Her only foray into the outrageous occurred at a Thierry Mugler fashion show in Paris when she strode down the runway in giant shoes and performed a striptease. Another sighting in the spotlight was when she acted in the musical Cry Baby with Johnny Depp. Other than that, the newspaper heiress has largely stayed out of sight describing herself as “just a boring old small-town mom,” not surprising for someone who had garnered far more than her fifteen minutes of infamy. Few echoes of the past followed her to Wilton, Connecticut, an old-moneyed town of large houses where neighbors included Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones and actor Paul Newman. The nod to yesterday is the home has a state-of-the-art alarm system and guard dogs. But what permeates the security is the indelible shadow cast by the SLA that will never completely disappear, as will questions over whether Tania was in actuality Patty’s violent alter ego or merely a brainwashed pawn. In either contingency, it is safe to assume that the designer-dressed matron represents everything Tania hated.

Currently, a widow with adult daughters, whom it is safe to say, she never admonished with the words, “When I was your age…” she breeds “Frenchies-” a more voguish version of the traditional English bulldog, a breed that she presented at the Westminster Kennel Club show at Madison Square Gardens. On that occasion, the verdict went her way when her puppy, Diva, took home a prize and offered the public a glimpse of what had happened to a post-urban-guerilla bank-robber-heiress.

There are still no easy answers in the curious case as to how Hearst metamorphosed from carrying a carbine to holding a grooming brush, but as Patty knows, the past, like a bulldog’s jaw, never lets go. The truth as to her role in the Symbionese Liberation Army provides a link to her grandfather’s celluloid alter-ego-Charles Foster Kane dying word lay behind his mystery and can represent his granddaughter’s own: “Rosebud.”