Fearless

The act of running weaves throughout the film Forrest Gump: when the bullies chase Forrest he runs; when the Viet Cong fire at Forrest he runs; when Jenny breaks his heart he runs. The same phenomena dominated the days of Kathrine Switzer, the first woman to complete the all-male Boston Marathon as an official entrant.

The Boston Athletic Association (BAA) founded the famous race in 1897 the year after the revival of the Olympic Games in Greece. The legendary event has its precedent in the legend that in 490 B.C. Pheidippides ran from Marathon to his native Athens (a distance of approximately twenty-five miles,) to announce his city had won the Battle of Marathon, then died from exhaustion on the floor of the Greek Assembly. In the modern era, the BAA made its event to coincide with Patriots’ Day, a New England holiday celebrated on the anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Since the first Marathon commemorated the historic run of a messenger, the Boston Marathon commemorated the historic midnight ride of Paul Revere.

Kathrine Virginia Switzer was born in 1946 in Amberg, Germany, when her pregnant mother, Virginia, went overseas to join her husband, Homer, a U.S. Army major. What marred their reunion were scenes from a devastated post-war Germany. In the hospital, the anxious new father filled out the birth certificate and omitted the “e” in the middle of Katherine. Little did he imagine the error would impact his daughter’s life and alter an American athletic institution.

Three years later, the Switzers returned to Fairfax County, Virginia, where Kathrine attended Madison High School. After informing her father she wanted to be a cheerleader, he responded, “You shouldn’t be on the sidelines cheering for other people. People should cheer for you.” Heeding his advice, Kathrine became a member of the girls’ field hockey team. To get in shape, she took daily runs despite warnings it would result in big legs and a moustache. Smitten, to borrow Forrest’s words, “From that day on, if she was goin’ somewhere, she was running!” She also worked on the school newspaper because of the dearth of coverage of girls’ sports, a fact Switzer sought to change. Because her name was always misspelled, she decided to use the byline K.V. Switzer, an idea she patterned on idols J.D. Salinger, T. S. Eliot, and e.e. cummings.

As a journalism major at Syracuse University, Kathrine bypassed the sorority route and trained on the men’s cross-country team as there was no women’s equivalent; her roommates snidely referred to her as Road Runner. A perk of membership was football player, Big Tom Miller, a 235 pound nationally ranked hammer thrower and Olympic hopeful with whom she began to go steady. The twenty-year-old was likewise enthralled with Coach Arnie Briggs who had participated fifteen times in the Mecca for runners: the Boston Marathon. One afternoon Arnie and Kathrine were running-despite blizzard conditions-as he regaled her with his racing adventures. He was taken aback when she told him something-the physical equivalent of an avalanche: she wanted to do more than hear about the race. His response, “No dame ever ran the Boston Marathon.” He repeated the zeitgeist that if they did something that arduous, it would turn a female’s features into a man’s; a doctor had previously informed her that to undertake such a feat, her uterus would fall out. Unable to dissuade her, Arnie grudgingly agreed that if she managed to run 26 miles, he would escort her to Boston. Weeks before the event, Kathrine completed a 31-mile practice run while an overly exerted Arnie fainted in her arms. A damper on the big day was Tom’s reaction; he said he would be joining her because if a girl could do it, he could do it as well.

Because of the frigid temperature on the day of the race, Kathrine had to forego wearing her burgundy top and shorts and donned a bulky men’s gray sweatshirt that Arnie had salvaged from the locker room at Syracuse University. Four miles later, no longer cold, she tossed her sweatshirt, a fact that alerted reporters there was a woman participant- something that did-not-sit-well with official, Jock Semple. He jumped off the press truck, screamed at Switzer, and ripped the corner of her bib. Tom threw a block that knocked Semple out of the way: photojournalists snapped pictures of the incident, and it became the American Revolutionary equivalent of the shot heard around the world. As the truck carrying the journalists followed, the reporters shouted, “What are you trying to prove?” “When are you going to quit?” A random man shouted, “You should be back in the kitchen making dinner for your husband.” Then Semple went by on another vehicle, yelling in his Scottish brogue, “You are ere een beeeeeggg trouble!” Over the next twenty-four miles, Switzer feared officials had contacted the police to drag her off the course. By Heartbreak Hill, the infamous incline that tortuously signifies the final six miles of the Marathon, Switzer had become an accidental activist, determined to cross the finish line, even if she did so on hands and knees.

Switzer completed the race in four hours and twenty minutes, having left Tom behind. At the finish line, a journalist sneered, “Are you a suffragette?” Retribution was swift: Semple disqualified Kathrine and expelled her from the AAU. She received hate mail and negative press reports. Journalist Jack McCarthy wrote she had posed an unnecessary problem for the race organization and that if he “didn’t abhor women golfers so much, woman marathoners would be number one on his list.” Will Cloney stated in the Sunday New York Times, “If that were my daughter, I’d spank her.” She ignored the negativity and realized her real race lay ahead: the fight for female acceptance.

Flak flew at Semper on the romantic front as well. Tom fumed her “jogging” had resulted in his attack, an action that would shadow his future. After their wedding, he explained that as he was the serious athlete, their focus had to be his entry in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. As it transpired, Tom actually helped his wife become a better runner; she was so anxious to avoid him she sprung out of bed every morning at 5:30 AM to train. One evening, after returning from marriage counseling alone-hubby refused to attend-when Tom did not look up from his show, Kathrine-not having an Olympic hammer in hand, used her high leather boot to smash the television screen. Although she never reconciled with Tom, in 1973 she reunited with a mellowed Jock who told her, “Come on, lass. Let’s get ourselves a wee bit of publicity,” and planted a kiss on her cheek.

In order to distance herself from a marriage that could not make it to the finish line, Kathrine headed to Munich for its Olympic Games as a sports journalist for the New York Daily News. What began as a dream working vacation morphed into a waking nightmare when members of Black September, Palestinian terrorists, released their homicidal hatred by murdering six Israeli athletes and six coaches.

During the ancient Olympics, wars were suspended to concentrate on the art of athleticism. Pierre de Coubertin reinstituted the Games to institute a spirit of international brotherhood and created the Olympic flag of five interlocking rings to represent the five continents. Four decades after the devastation at Munich, Kathrine was a broadcaster at the Boston Marathon and had just returned to her hotel room when she heard a bomb detonate. She believed it was a gas explosion until a second blast. She wanted to help the victims when her third husband, Roger Robinson, a British-born world class runner, informed her the hotel was on lockdown. A pressure cooker packed with nails had been planted at the race’s finish line that resulted in three deaths and injured 260.

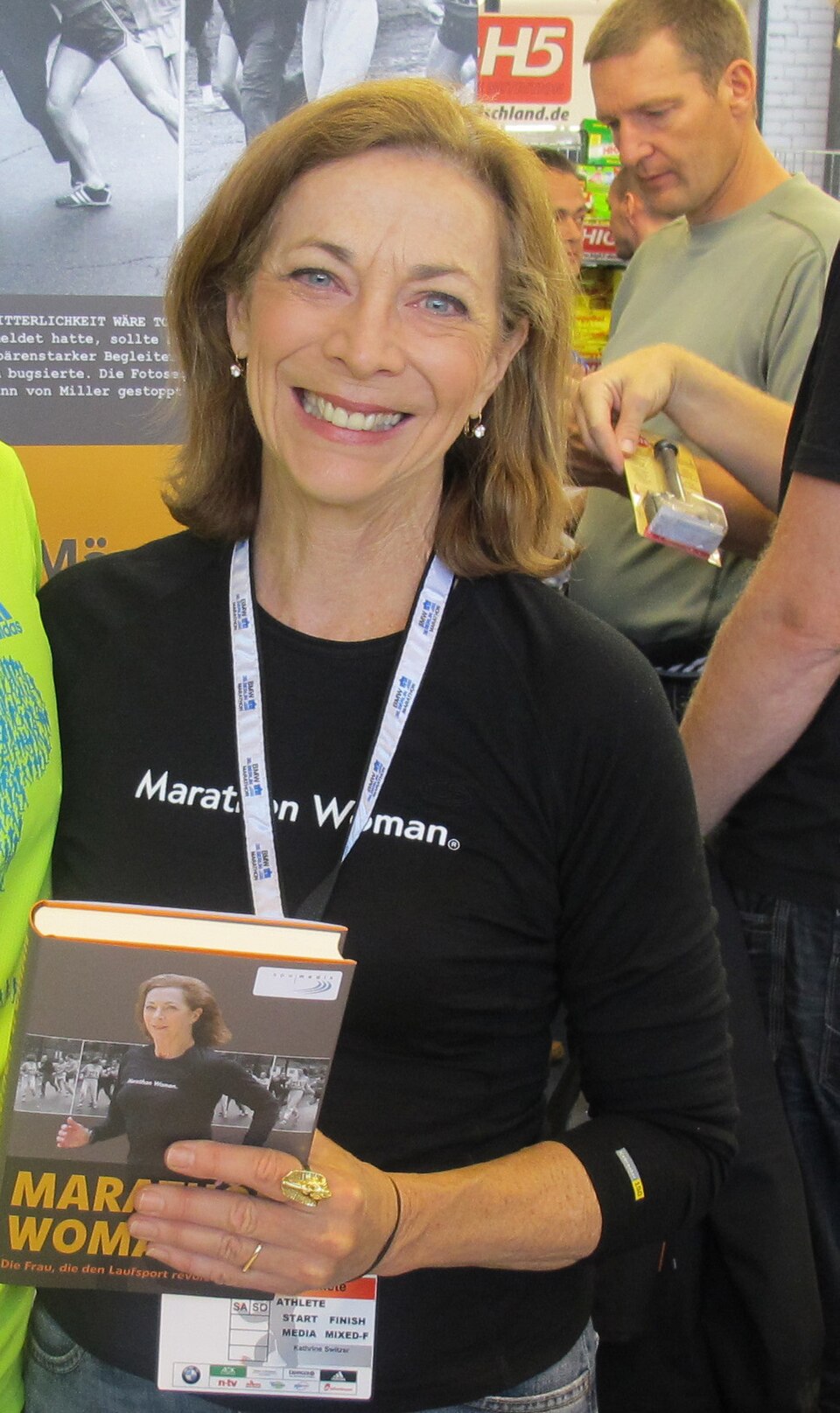

Fifty years after her first Boston Marathon, the seventy-year-young Kathrine ran the route once more where she finished the race just under twenty-five minutes slower than her earlier time of four hours and forty-four minutes. In the vein of Bob Dylan’s “The times there are a changing,” approximately one million fans cheered her on and photographers and television cameras captured her victory at the finish line. Rather than having her bib torn off, officials chose her to fire the starting gun. Switzer wore her original bib number of half a century before-which the organizers retired as a mark of honor. In her memoir, Marathon Woman, Kathrine stated that her experience had mimicked the social revolution of the sixties and that she was proud of her activism. Women were officially allowed to compete in the Boston Marathon in 1972, a watershed event Kathrine felt was the equivalent of the suffragettes obtaining the vote. Of that landmark decision, she stated, “In 1967, few would have believed that marathon running would someday attract millions of women, become a glamor event in the Olympics and on the streets of major cities, help transform views of women’s physical ability and help redefine their economic roles in traditional cultures.” Currently, 58 percent of marathon runners in the United States are women. Kathrine is thankful to Jock for one of the most galvanizing photos in women’s rights history.

To date, Kathrine has entered more than thirty marathons, winning in New York in 1974 and has worked as a television commentator and as a contributor to Runner’s World magazine. She founded a women’s running club, threw out the first pitch at a Boston Red Sox game, and arranged for the Golden Gate to be closed in the San Francisco Marathon. In 2011, the National Women’s Hall of Fame inducted her as a member. Of her legacy, Switzer said that it came as no surprise that females continued to embrace the “sense of empowerment” that came with the territory. “We have come a light year, really. But we have a long way to go.” Kathrine was referring to the fact that female sports figures still encounter gender discrimination as it relates to pay and publicity. In tribute to the one who had done so much, her bib number is often worn by women on their arms when they race; others have it emblazoned as a tattoo. The most endearing gesture for Switzer was four young girls who had her number written on their cheeks or foreheads who held up signs that read, “Go Kathrine Switzer! Equality for all of us!”

Great events hinge on minor ones; had it not been for the freezing 1967 temperature, Switzer would not have become one of the historic figures in America’s most famous race. Had she not needed a thick sweatshirt, there might not have been a marathon for women at the 1984 Olympics. Because of the convergence of the chill of a Boston afternoon and the overzealous Jock Semple, thousands of women realized they could run twenty-six miles-without growing a moustache, without losing their reproductive abilities.

The Renaissance woman founded a non-profit organization that uses running to empower women around the world. She christened it after women’s indomitable spirit and the number on her bib on the fateful day that altered the course of her life: Fearless 261.