A Stone Angel

Larry Flynt, whose pornographic empire forever arm-wrestled the First Amendment, railed, “The church has had its hand on our crotch for more than 2,000 years.” A tireless crusader also fought for sexual autonomy, but her ends were salvation, not debasement.

In reaction to Donald Trump’s campaign against Planned Parenthood, protests erupted: to defend or to defund the century-old organization. If the woman who had stirred up this storm had been present, she would no doubt have been pleased; she made a career out of drawing attention to herself on behalf of her Holy Grail.

Margaret Louise was born into a hardscrabble life in 1879 in Corning, New York, the daughter of Irish immigrants. Her father, Michael Hennessy Higgins, was a mason who chiseled monuments on tombstones by day and drank by night. Her mother, Anne, underwent 18 pregnancies and bore 11 children in 22 years; she passed away at 49 from tuberculosis. Determined not to follow in her mother’s worn-down footsteps, Margaret left to New York City where she became active in theatre. She aspired to become an actress but had a change of heart when she discovered this career choice would entail having to divulge her leg measurements.

In 1902 Margaret married William Sanger, an architect by profession and socialist by passion, hell-bent in rebelling against his conservative Jewish family. Their Greenwich Village home was filled to overflowing with their three children and the greatest rabble-raisers of the era such as Emma Goldman. The militant feminism of the Russian-Jewish Emma resonated with the Irish-Catholic Margaret, and they shared the philosophy that women had to be emancipated from the reproductive consequences of intercourse. In contrast, the power players believed the only acceptable form of birth control was abstinence. “Can they not use celibacy?” demanded Anthony Comstock, leader of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, “Or must they sink to the level of beasts?” His proudest boast was he had destroyed hundreds of tons of “lewd and lascivious material” including 60,000 “obscene rubber articles,” otherwise known as condoms.

Sanger’s sexually radical thinking was reinforced through her nursing position in the Lower East slums of Manhattan. She took umbrage with the Book of Genesis that exhorted the descendants of Adam and Eve “to be fruitful and multiply;” the tenements manifested the only result of the biblical injunction was broodmare mothers and neglected children. Many of her patients-old at 35-resorted to self-induced abortions, risking death to end pregnancies they could not avoid. In an era when buying a single condom was criminalized in thirty states, and priests warned parishioners preventing contraception was an entry ticket to Hell, Old Wives tales “to do the trick” proliferated through the slum grapevine.

On a stifling July day in 1912, Margaret was assisting Sadie Sachs who had attempted to terminate her fourth pregnancy. She begged the doctor for information on how to prevent a fifth; the response: “Tell ‘Jake’ to sleep on the roof.” When Sadie passed away six months later during a second self-induced abortion, Sanger decided her life’s crusade was to end ‘involuntary motherhood.’ She became a self-appointed evangelist, her pulpit: sex separated from procreation. She was prepared to step into the boxing-ring, knowing full well her opponents would be powerful: the Catholic Church, the American government, and public opinion.

Although the movies of the era were silent, Ms. Sanger was not, and she published the periodical, “The Woman Rebel.” The term “birth control” first appeared on these pages, under the slogan: No Gods; No Masters. She also wrote a sex education column, “What Every Girl Should Know,” for a left-wing newspaper, delivered through the mail. When Comstock banned her editorial on venereal disease, the paper ran an empty space with the title, “What Every Girl Should Know: Nothing, by Order of the U.S. Post Office.” Comstock had enough of the thorn in his side and indicted Margaret for decimating obscenity; her argument she was exercising her First Amendment rights fell on deaf ears. On the eve of her trial, faced with a prison term of 45 years, she fled to Europe. Before her escape, she distributed 100,000 copies of “Family Limitation”; she wrote friend Upton Sinclair that Comstock now would have something “to really indict me on.”

William Sanger was left with the care of the children, not sweetened by the news his wife, in England, had begun beds a trois or a quatre and had embarked on affairs with novelist H. G. Wells and psychologist Havelock Ellis. A further sling from the marital quiver arrived when an undercover vice officer went to the Sanger home and represented himself to William as an impoverished father and purchased “Family Limitation.” At Willliam’s trial he admitted he had broken the law, but he maintained it was the law itself that was on trial. The judge, a devout Catholic, called William “a menace to society” whose crime violated “not only the laws of the state, but the laws of God.” He sentenced Sanger to thirty days in prison. Because of Margaret’s efforts, public attitude had changed and the charges against her were dropped a month later. She returned to the States; shortly after her five-year-old daughter Peggy died of pneumonia.

In 1916-four years before women got the right to vote- the indefatigable Sanger opened the first birth-control clinic in the United States behind the curtained windows of a storefront tenement in Brooklyn. Handbills advertising the facility were passed out in English, Yiddish, and Italian. By her side was her sister Ethel Bryne, whose daughter, Olive, would serve as the muse behind the Justice League’s Wonder Woman. Hundreds of women lined up for blocks; apparently the men of New York were not keen on sleeping on the roof. The police raided it ten days and 46 patients later. Margaret, shouting an[JL1] Irish invective at the officer, landed in jail. In prison-where she spent a month-she spread the word of contraception to her fellow inmates. Ethel, also in custody, embarked on an eight day hunger strike that almost led to her death. Sanger, who would go on to lunch the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, founded something far greater than a clinic: she had ignited a movement for women’s reproductive freedom.

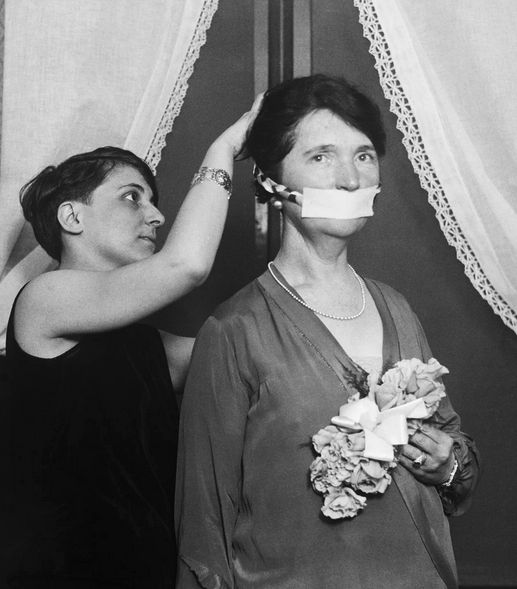

In 1921 Sanger organized the first American birth control conference at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan, and her sponsors included Winston Churchill, the Rockefellers, and Theodore Dreiser. When the authorities forbade her to speak in Boston’s Ford Hall, she stood silent on the stage, her mouth taped shut, while a Harvard University historian read her prepared statement. Democratic in the choice of audience, she also lectured for the female members of the Ku Klux Klan in New Jersey. Some view this through the lens of Sanger as a proponent of eugenics, especially against African Americans; the opposite perspective was she only cared about alleviating the anguish of women, desperate not to bear children for whom they could not provide. Her philosophy was quality of care rather than quantity of offspring should comprise a mother’s mantra.

Sanger once remarked to a lover she was “not a peaceful or restful person to know at all.” Apparently, William concurred, and the Sanger marriage, after several years of separation, ended in 1921. She confided that she would not remarry, except for money; the following year she wed Noah Slee, 17 years her senior- a millionaire. He adored her enough to allow her to continue her independent life and liaisons and served as a financial angel for his wife’s activism. Slee was the largest individual supporter of the American Birth Control League, and he donated $50,000, ten times more than anyone else. In addition, he purchased a five- story townhouse for the clinic. Margaret, as eagerly as she had once courted socialists, took to wooing socialites, writing, “Little can be done without them.” Before she became First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt was a staunch supporter.

When the pill-that Margaret helped fund was approved in 1960, she was a widow living in an Arizona nursing home and celebrated by uncorking a bottle of champagne. Her old disagreement with the Roman Catholic Church-and her belief it was time for the rosaries to get off the ovaries-led her to say if the Catholic Kennedy won the presidency she would flee the country once more. However, she softened her stance when informed the Senator and Jackie were sympathetic toward the problem of overpopulation. Sanger, who died in 1966 at the age of 87, had the comfort of knowing that the United States Supreme Court had made its historic 1965 decision in Griswold v. Connecticut that gave Constitutional protection to the private use of contraceptives-though with the addendum it applied within the confines of marriage.

Posterity’s evaluation of Margaret lies in the murky arena of subjectivity: to those who are of the school of the rhythm-method of birth-control, she is Satan’s handmaiden; for the advocates of the pill, she is what her father carved on tombstones: a stone angel.

[JL1]I added an here.