Any Wars?

“I must admit I enjoy being in a war.”

Society is well-versed in the “trials of the century:” the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby, the judgement of the war criminals in Nuremberg, the People v. O. J. Simpson. What has slipped through the cracks of history is the woman behind the “scoop of the century.”

Patrick Garrett saw a battered trunk, covered in dust and exotic shipping labels, in the attic of his parents’ London home. The relic belonged to his great aunt who loomed large in family lore. Upon opening the valise, Patrick saw passports, rolls of film, foreign bank accounts. Among the jumble were sepia-colored photographs of his great aunt’s lovers. There were also letters of gratitude that revealed his relative had been the British Oskar Schindler.

Born in the same year as Tennessee Williams, Lucille Ball, and Ronald Reagan, Clare Hollingworth experienced World War I as a child in Britain when she saw German bombers flying over her family’s farm. Her father, Albert, worked at his shoe and boot factory, but in his time off, he took Clare and her pony, Polly, to investigate the damage inflicted by a Zeppelin raid. Despite introducing his child to the mysteries of the military, he and his wife, Daisy, disapproved of “educated women” and sent Clare to study at a domestic science college for “lady wives” located in a building that had formerly housed a mental asylum. The result of her course was hatred of all matters concerning domesticity. Clare later admitted that it was useful to have mastered how to make an omelet. With her leftist politics and bookish ways, both her family and town did not know what to make of her. In deference to her upbringing, Clare became engaged “to a suitable young man,” a betrothal of which both set of parents approved. Upon her realization that he “was not my dish,” she ended their relationship. She further upset her parents by announcing her decision to become a journalist. Clare later told an interviewer, “My mother thought journalism frightfully low, like a trade. She didn’t believe anything journalists wrote and thought they were only fit for the tradesmen’s entrance.”

As her aspiration would entail further education than the one she had obtained in domestic science classes, through a scholarship, Clare attended the school of Slavonic and East European Studies in London, followed by a program to learn Croatian at the University of Zagreb, then part of Yugoslavia. Post studies, Clare obtained a secretarial position at the League of Nations Union, a peace and social justice group established in 1918.

In that capacity, she met colleague Vandeleur Robinson, a mustachioed, bespectacled intellectual ten years her senior. Clare was taken with his knowledge of foreign affairs, so much so she toured the Balkans with him, despite the fact there was a Mrs. Robinson. After his wife divorced him on the grounds of infidelity, he asked for Clare’s hand. She only agreed when she learned that marriage did not necessitate relinquishing her maiden name. Clare became the eighth woman in England to hold a passport that did not include a husband’s surname.

Hollingworth ended her secretarial stint and volunteered for a daring mission: to travel across Germany to the Polish port of Gdynia to rescue refugees fleeing from the Nazi takeover of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland. The humanitarian organization chose Clare as she had a German passport, one left over from a Christmas vacation in Kitzbühel, the Austrian ski resort frequented by the Prince of Wales, author Ian Fleming, and high-ranking Reich officials. Among the thousands she assisted was two-year-old Madlena Korbel; history remembers her as Secretary of State Madeline Albright. Clare also aided Austrians and Germans who had opposed Hitler and helped them cross the border into Poland disguised as peasants. For verisimilitude, she supplied them with chickens to make them seem like farmers. For her daring rescues, the English press dubbed her “the Scarlett Pimpernel,” an allusion to the character in Baroness Orczy’s novel who helped aristocrats flee the French Revolution. In contrast, British officials were not impressed with some of the communists and what they considered other undesirables she was smuggling into their country, and her employers ended their association. Upon her return to London, Clare contacted the editor of the Telegraph who offered her a job as an assistant to Hugh Carleton Greene (later Sir Hugh Greene, brother of novelist Graham Greene) in Poland.

As only diplomat’s vehicles were permitted to cross the border, Clare turned for help to her former lover, the British Counsel General, John Thwaites, whose car displayed a Union Jack. The trip proved uneventful, and she purchased as much wine, aspirin, and film as she could as these items were not available in Poland. She was heading back, driving along a steep hillside, when she noticed that huge tarpaulins were concealing the valley from passing traffic. A gust of wind lifted a loose piece of fabric that revealed the presence of thousands of Wehrmacht tanks lined up in battle formation. Hollingworth had chanced upon the greatest scoop in history: the invasion that ignited World War II.

In her Katowice room, Clare contacted the British embassy in Warsaw with the words, “It’s begun.” After the official skeptically asked, “Are you sure, old girl?” Clare held the receiver outside her window so he could hear the sounds of German planes and Panzer tanks. The next morning, the Daily Telegraph headline proclaimed: 1,000 TANKS MASSED ON POLISH FRONTIER-TEN DIVISIONS REPORTED READY FOR SWIFT STROKE. The British paper, The Guardian, described it as “probably the greatest scoop of modern times.” Two days later, Clare heard on the radio that Britain had declared war on Hitler. Anxious to obtain information, Clare slept in a car where she kept wine and biscuits. She said of those days that you could go anywhere with a T and T, a typewriter and a toothbrush.

With the arrival of the Russians, Clare took off for Bucharest where she remained until 1949. She assured her newspaper that she would not return home to be with her husband, “Good God, no! Oh, no. Not. At. All.” Her relationship with Vandeleur was effectively over, and fifteen years later he divorced her on the grounds of desertion. She explained, “When I’m on a story, I’m on a story-to hell with husband, family, anyone else.” Her second husband was Geoffrey Hoare, a writer for The Times, who polished her articles before she sent them off to her editors. The couple departed for Jerusalem to cover the bloody birth of Israel. She recalled the day of the bombing of the King David Hotel detonated by militant Zionists as one of the few occasions she experienced fear.

A huge domestic battle ensued in the couple’s Paris home when Clare discovered hubby was having an affair. Hollingworth confronted Joan Harrison, the other woman, and threatened to shoot her with her pearl-handled pistol if she ever slept with her husband again. Holding on to her man may have been for practicality as well as romance. Clare depended on Geoffrey to help with her writing that was not on par with her reporting skills. Perhaps to fend off any divorce, Clare converted to Roman Catholicism. Despite his alcoholism and womanizing, Clare was devastated at Geoffrey’s passing; it was the only occasion she ever asked for time off. She confided that she missed him every night in bed, the place where they had drunk beer and discussed current events. Clare admitted she had an affair after Geoffrey’s passing, but it was a complete failure. Hollingworth said it would have been lovely to have had a boyfriend for a trip to Timbuktu or Togoland. She expressed her philosophy, “A good gin-and-tonic gives me more pleasure than any man.” She took pains to never become pregnant, “I would so greatly prefer the noise of the guns in Beirut to children. Am I wicked?”

As part of her journalistic duties, in order to obtain insight into the Royal Air Force, Clare obtained her pilot’s license and learned how to parachute. On a night foot patrol behind enemy lines, she was trying to sleep when she heard German voices nearby. “What did I do? Put some more sand over my head and hoped for the best.”

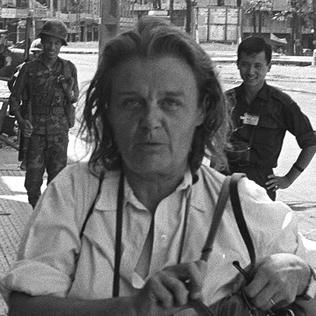

A non-celluloid Forrest Gump, Clare Hollingworth interacted with the major events and power players of the twentieth century. She covered World War II from Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and North Africa and wrote of the bitter enmity between Arabs and Jews as the curtain closed on the British Empire. Ms. Hollingworth often said she was never as happy as when she was on the road even though she did so a stranger to creature comforts. She slept in tracks and trenches, once buried up to her neck in sand for warmth on a frigid desert night. Even in the confines of a hotel, she often roughed it by sleeping on the floor so she wouldn’t “go soft.” In Vietnam, a sniper’s bullet narrowly missed her head. For the Algerian Civil War, she entered the Casbah-the epicenter of violence- akin to a suicidal mission. Hollingworth had the honor to become the first resident correspondent in Beijing since the imposition of “the bamboo curtain.” At age eighty, attired in her habitual safari attire, she shimmied up a lamppost to gain a better view of the crackdown in Tiananmen Square. Her last major posting was on the death of Mao Zedong and the ensuing power struggle. For fifty years, the 5 ft. 3 inches tall Ms. Hollingworth pursued danger as that was where, she explained, the best stories awaited. An intrepid journalist, she ran to the places all else were running from.

Through her vast networks of connections and bulldog tenacity, she acquired interviews with the world’s most renowned: Mohammed Reza Pahlavi after he became the shah of Iran in 1941, and his last, in 1979, after the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini swept him from his peacock throne. In 1965, desirous of reporting on the hostilities between India and the newly birthed Pakistan, as reporters were not permitted on the front, she called on a favor from an old acquaintance, Indira Gandhi, then India’s minister of information and broadcasting. Other famed meetings were with Henry Kissinger, “I thought very highly of him,” and Margaret Thatcher, with whom she was not impressed.

Clare made her final home in Hong Kong. The governor, Lord Murray MacLehose, an old friend, found her a part-time job at the University of Hong Kong. She rented a two-bedroom apartment with a view of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club (FCC). The Club reserved a “Clare’s Table” for the 105-year-old grand dame of journalism. Traces of her abrasive personality remained: she banged her cane on the floor to catch an inattentive waiter’s attention, talked in a loud, strident voice, a remnant from communicating with her father who had become almost deaf in his later years. Despite failing eyesight and advanced age, Clare maintained her old habits such as drinking bottled beer for breakfast. Not one to see the advantage of retirement, she slept with her shoes by her bed and passport in nightstand in case a new scoop beckoned. Queen Elizabeth II made her a recipient of the Order of the British Empire. The human whirlwind can best be understood by her incessant question to editors, “Any foreign trips going? Any wars?”