Shall Lead Them

“Let us pick up our books and pens. They are our most powerful weapons.” ~Malala Yousafzai

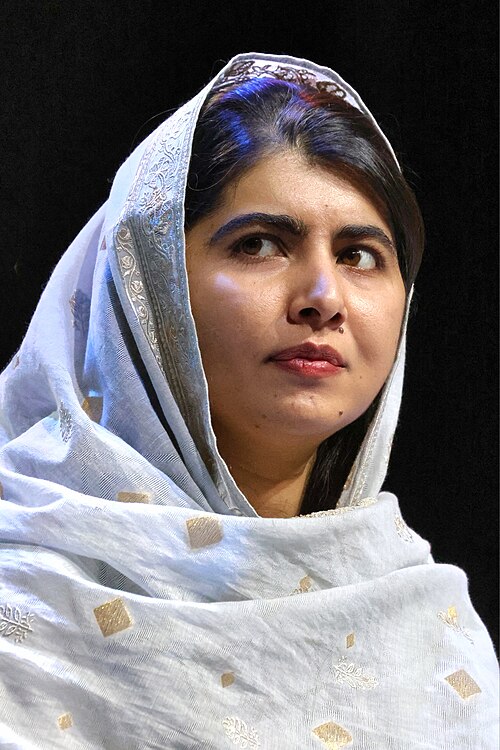

Aren’t teens terrible? The films Animal House, Carrie, and Mean Girls would answer the question with a resounding “Yes!” However, Malala Yousafzai is a non-celluloid example of a teen titan who arm-wrestled inequitable education.

Nature was bountiful in the creation of the Swat Valley, Pakistan, that erected the country’s first ski resort that led to its moniker “the Switzerland of the East.” Queen Elizabeth II stayed in the White Palace, the residence of the first king of Swat, constructed from the same marble as the Taj Mahal. A sign at the entrance to the valley reads: Welcome to Paradise.

In this enclave of beauty, Ziauddin Yousafzai and his wife, Tor Pekai, awaited their first-born. Too poor to afford a doctor, a neighbor woman assisted in the birth. As Tor Pekai delivered a daughter, the town commiserated with the parents; had she been a boy, they would have celebrated by firing their rifles. The proud papa turned to his Pashtun culture for a name and chose Malala based on Malai of Maiwand-who perished fighting the British. His family tree, that went back 300 years, received its first female entry: Malala Yousafzai. As a child, she disliked her name that meant “grief-stricken.” She preferred Mahrow-Moon Face,-that she had discovered from a book. As their culture stipulated it was disrespectful to use a relative’s name, and as it was her grandmother’s, she did not receive her wish.

The family lived in Mingora, the valley’s only city, in the suburb of Gulkada, (the place of flowers.) In ancient times, Swat had been a Buddhist kingdom called Butkara, (place of the Buddhist statues.) When Malala enjoyed picnics in a neighborhood field she did so in the proximity of the earlier religion’s monuments that consisted of stone lions, broken columns, umbrellas, and Buddhas. In her free time, she played cricket with her younger brothers: Khushal (named after the Pashtun hero Khushal Khan Khattak, a warrior and poet,) and Atal.

Ziauddin owned the private elementary Khushal School where his children were among his 800 students. The curriculum included the study of Pashto, Urdu, and English; other courses covered science, history, and Islam. His daughter loved school so much that despite attending classes six days a week, in her free time she playacted the role of a teacher. She shared lessons with Tor Pekai who was illiterate. Her mother had been denied an education due to her sex, and could not enter a mosque, a male domain. Malala’s favorite pastimes were reading the Twilight series, watching the television series Ugly Betty, and listening to Justin Bieber songs, often with Moniba, her closest friend. For sports, she played cricket with her brothers.

Rather than spending evenings with women, Malala listened to the men recite the works of Rumi, the Afghan poet. However, in 2008 their talk turned from poetry to politics due to the emergence of the gun-toting Taliban who had infiltrated the Swat Valley. The Talban banned music, dancing, movie theaters, television, and computers. They demanded women wear burqas, leave home only in the company of a male relative, and could no longer vote or work. What sent shivers down Malala’s spine was the new regime ordered class dismissed for girls that threatened her dream of becoming a doctor. The gender apartheid also threated women’s health as females could no longer practice medicine or seek treatment from male physicians.

By the end of 2008, more than 150 girls’ school had closed; however, Ziauddin refused to turn away his female students. To deflect attention, Malala stopped wearing her blue school uniform. When the British Broadcasting Corporation’s Urdu website asked Ziauddin if one of his students would write blogs about daily life under the Taliban, eleven-year-old Malala took on the task. While turbaned terrorists ravaged her country, the diminutive David spoke of the injustice of denying education to half the Pakistani youth. The result was “Diary of a Pakistani School Girl:” as anonymity was essential, Malala published it under the pen name Gul Makai (the name of an inspirational girl from a Pashtun folktale.) A year later, the New York Times released a video that featured her carrying a schoolbag satchel that featured Harry Potter.

For the next three years, she served as a microscope to the outside world as to a young girl’s reality under an oppressive regime. In the process, Malala became a symbol of home in a land that had very little of what was at the bottom of Pandora’s Box. However, as her renown spread so did the danger of exposure.

Eventually, the Khustal School closed. A few months later, in 2009, the Pakistani army launched an attack on the Taliban that led to the evacuation of Swat residents, including the Yousafzai family who fled to Abbottabad, (the site where Osama bin Laden met his end.) The winds of war seemed to favor the army as the Taliban beat a retreat to their stronghold in Afghanistan. The ancient valley dared dream of peace. During this time, Malala, who had continued her role as the chronicler of Pakistani youth, and in 2011, the anti-Apartheid South African Anglican bishop, Desmond Tutu, announced her nomination for the International Children’s Peace Prize. Yousaf Raza Gilani, Palestine’s prime minister, awarded her the country’s first National Youth Peace Prize. (The award subsequently became the National Malala Peace Prize.) When an interviewer asked her how she combated her ever present danger, Malala responded that even if the Taliban ambushed her she would tell them what they were doing was wrong and that education is a basic right.

While Malala’s J’accuse! garnered empathy for her cause, her public exposure put her on the Taliban radar. The tide of Malala’s life irrevocably changed on October 9, 2012. As the fifteen-year-old was on her way to school, chatting with Moniba, a masked Pakistani Taliban boarded the bus. He asked the terrified children, “Who is Malala?” When the children turned in her direction, he shot Malala; the bullet graze her brain and lodged in her neck. The shots also injured two other students. While the other victims received non-life-threatening wounds, their intended victim was left on death’s door. A helicopter flew the seriously injured teen to a military hospital in Peshawar. Reporters gathered outside the hospital, and her picture and the news appeared throughout the world. On a phone call, the assassin, Ehsanullah Ehsan added that her crusade for egalitarian education was an “obscenity.” He elaborated, “She has become a symbol of Western culture in the area; she was openly propagating it.” Ehsan ended vowed, “If we found her again, then we would definitely try to kill her. We will feel proud upon her death.” The act of brutality backfired as it solidified the world’s perception of Malala’s courage and the Taliban’s barbarism. However, the assassination showed the country had harbored a false sense of security and the enemy at their gates were an ever-present danger.

The president of Pakistan arranged for Malala’s helicopter airlift to Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham to receive life-saving surgery. Fearful of their safety, and to be with Malala, the Yousafzai family headed to England. Apprehensive of returning to their home after their stay in Peshawar, they arrived in Birmingham with the clothes they were wearing as their only possession.

Initially, Malala’s injuries were so severe she was unable to speak and communicated with her physicians by writing in her notebook. After a few months, she improved and was able to move her facial muscles and smile. Although thankful to leave the Taliban in their rearview mirror, she missed the Swat Valley, that was 4,000 miles away in both distance and character. She felt like the biblical stranger in a strange land. When Malala first walked out of the hospital her purple parka offered scant protection from the unfamiliar frigid weather. Malala recalled she felt like she would never warm up, and the grey, gloomy sky and snow-covered ground made her long for the sunshine of her valley home. She also felt like a fish out of water in her new residence in a Birmingham high-rise. Never having experienced an elevator, Tor Pekai felt it was like boarding a spaceship and during the ride to her floor she closed her eyes and recited a prayer. She would have preferred a ground floor residence like the one she had vacated and worried what would happen in the event of a fire or earthquake. When Malala saw what the British women wore, she wondered if their skimpy outfits was because of a national fabric shortage. She modified her school uniform by wearing a longer skirt and headscarf in keeping with the Islamic tenet of female modesty.

What was even harder to bear was the loneliness she experienced at school. How could the other girls relate to someone who had been the bull’s-eye of the Taliban? She greatly missed the comradery she had shared with Moniba, and her other friends in Mingora. She likened her alienation to a gnawing at her stomach “like a hunger I could not feed.” She said of her situation, “It’s odd to be so well known but to be lonely at the same time,” However, once ensconced in her apartment the loneliness eroded when she spoke Pashto, skyped with Moniba, and watched Indian soap operas with her mother. Despite these two diversions, Malala adheres to the “nose to the grindstone” philosophy. In her quest for great grades, Malala rarely watches television and deleted the candy Crush game from her iPad as she feared it was proving addictive and distracting. The only selfies she takes is when they serve to make a pollical statement on the behalf of egalitarian education. While women from her culture stain their hands with henna in traditional floral patterns, Malala’s bore calculus and chemical formulas from her science homework.

Another source of solace was the thousands of letters she received bearing stamps from various countries. Most arrived from women and girls who wrote of their appreciation of Malala standing up for their rights, for remembering them while they stood in the shadow. The letters arrived when Malala was at a crossroads in her life: whether to adopt the role of a British schoolgirl or once again take up the sword to fight injustice. She explained her decision with the words that the Taliban had failed in their mission. Malala said, “Instead of silencing me, they amplified my voice beyond Pakistan. People from all over the world wanted to support the cause I was so passionate about, they wanted to support me, and they welcomed me. That inspired me to continue my work.” Her hero is Benazir Bhutto who had been the first female prime minister of Pakistan; Malala was devastated at her assassination. Benazir’s children had visited Malala when she was in the hospital at which time they gifted her to of their mother’s shawls.

The cause she had started in Pakistan would continue in England. As she continued to be the voice of the voiceless, the indomitable activist drew admirers from Queen Elizabeth II to Angelina Jolie. At age fifteen, during her summer vacation, Malala flew to Nigeria to appeal to its president for the release of the 200 kidnapped girls who had been the victims of the extremist Islamist group Boko Harem. She also met with President Obama where she critiqued American military activities in Pakistan. She told the Chief Executive, “Instead of soldiers, send books. Instead of sending weapons, send pens.” When questioned to his response, Malala gave a knowing look and responded, “He’s a politician.”

In what must have been the most august of presents, Ban Ki-moon, the secretary-general of the United Nations, declared July 12, 2013, her sixteenth birthday, Malala Day. On that occasion, Malala delivered a speech at the United Nations in New York City; for the august occasion she wore Benazir’s scarf. She spoke in English while headphones delivered her speech into a multitude of languages. She exhorted leaders to wage a world-wide struggle against poverty, illiteracy, and terrorism. The power of her voice belied her years, “They thought that the bullets would silence us, but they failed. And out of that silence came thousands of voices. The terrorists thought they would change my aims and stop my ambitions. But nothing changed in my life except this: Weakness, fear, and hopelessness died. Strength, power, and courage was born.” In a nod to those whose lives had served as moral compasses, she mentioned Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and Mother Teresa. In keeping with her modest nature, she added, “Malala Day is not my day. Today is the day of every woman, every boy, and every girl who have raised their voice for their rights.” From their seats in the front row, Ziauddin beamed with pride; Tor Paka wiped away tears. The he media displayed clips of Malala’s speech with its tagline, “Education first.”

Three months later, the activist turned author with the release of her memoir, I am Malala. If being a best-selling teenaged author was not heady enough, another honor awaited. On October 10, 2014, while in her chemistry class in the Edgbaston High School in Birmingham, her teacher informed her that the Nobel Committee had nominated her as the recipient of its Peace Prize. The seventeen-year-old girl was to share the Award with the sixty-year-old Kailash Satyarthi. Of the joint nominees, Malala stated, “One is from Pakistan. One is from India. One believes in Hinduism. One strongly believes in Islam. And it gives a message to people, gives a message to people of love between Pakistan and India and between different religions. And we both support each other. It does not matter what’s the color of your skin, what language do you speak, what religion you believe in. It is that we should all consider each other as human beings.” Malala made history as the youngest person to ever receive the Nobel Peace Prize. During her memorable evening in Sweden, Malala received a gold medal bearing the likeness of Alfred Nobel, as well as half of the Prize money of $500,000. She funneled the proceeds into the Malala fund that helps children throughout the world to receive an education. Another donation: She gave her dark-blue-and-white uniform, stained with her blood from the Taliban bullet to the Nobel Prize Exhibition in Oslo. Another laurel: an asteroid bears her name.

When she returned to Birmingham, she referred to the prize as “an encouragement for me to go forward and believe in myself. Then added, “It’s not going to help me in my tests and exams.” While it is not unusual for graduating seniors to celebrate with a trip abroad, Malala’s was a horse of a different color. After receiving her high school diploma, Malala left for the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America to interview girls regarding their educational tribulations.

While Malala longed for the homeland that seemed forever forbidden, in 2012, while studying philosophy, economics, and politics at Oxford University, she left on a four-day visit to Pakistan. Security was heavy when the Yousafzai family arrived at Benazir Bhutto International Airport. In an emotional meeting in Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan’s office she said, “I still can’t believe that it is actually happening. In the last five years, I have always dreamed of coming back to my country.” She also visited the two Peshawar-based doctors who performed her first surgeries. While most of her time was in Islamabad, she also visited the Swat Valley, and the site of the attack. In the nearby neighborhood of Shangla she inaugurated a school for girls, erected with funds the proceeds of the Malala Fund. Although most were welcoming, not all were in Camp Malala. In the city of Lahore, students and staff held up placards: I Am Not Malala Day.

While activism continues to be Malala’s mission, she has left room for romance. In a small Islamic ceremony in Birmingham, the twenty-four-year-old wed Asser Malik, the manager of the Pakistani cricket team. The bride wore a pink dress and head scarf; henna decorated her hands. Malala’s The Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl echoes the biblical quotation, “A little child shall lead them.”