That Word is Liberty

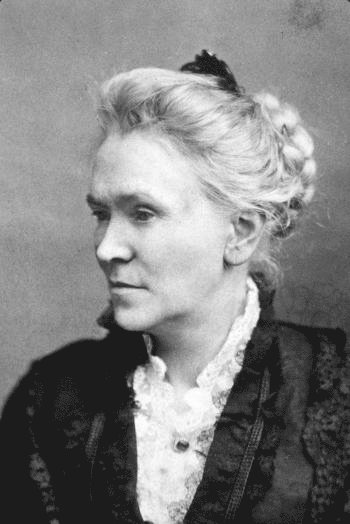

Matilda Joslyn Gage

“The government of the people, by the people, and for the people should be changed to a government of rich men, by rich men, for rich men.”—Matilda Joslyn Gage

After her realization that the Wizard of Oz was a humbug, Dorothy informed him that he was a very bad man. His response, “Oh, no, my dear. I’m a very good man. I’m just a very bad wizard.” In contrast, Matilda Electa Joslyn Gage, the woman behind the curtain of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, was both a good woman and a good wizard.

In John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath, Tom Joad states, “Whenever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there.” And whenever there was an injustice, a nineteenth-century radical was there. Matilda was born in 1826 in Cicero, New York, the only child of Helen and Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn. At an early age, her parents swore her to secrecy: the visitors who arrived in a wagon, buried under hay, were what the museum terms “Freedom Takers” desperately fleeing their plantations. Dinner conversation revolved around abolition, gender equity, and outlawing alcohol. Desirous of following in her father’s footsteps, Matilda applied to Geneva Medical College Her effort proved futile as medical schools were a male domain. Upon Hezekiah’s passing, Matilda had his tombstone inscribed with the words, “an early abolitionist.” When asked what influences shaped her, Matilda replied, “I was born with a hatred of oppression.”

At age eighteen, in the Joslyn parlor, Matilda married Henry Hill Gage in a ceremony presided over by a minister from the Disciples of Christ Church. In 1854 the couple purchased a residence in Fayetteville, New York. The Gages christened the house Sunset View where they raised their four children (a fifth died in infancy). Matilda signed a petition stating that she would face a penalty of a six-month prison term and a thousand-dollar fine rather than honor the newly enacted Fugitive Slave Law. As the Joslyns had done years earlier, and prompted by a request from Reverend Jermaine Lougen, the Gages turned their home into a station on the Underground Railroad. On the day when John Brown swung from the gallows for leading an armed resurrection against plantation owners, Matilda put out black decorations on her home. Before the 122nd Regiment left for battle, she stated she disagreed with President Abraham Lincoln’s claim that the Civil War revolved around preserving the Union. For her, the battle’s goal had to be emancipation for all.

In 1852 Matilda decided to “publicly join the ranks of those who spoke against wrong” by taking part in a women’s rights convention in Syracuse, New York. In attendance was Susan B. Anthony, a future friend and collaborator. While other speakers outlined what women would be able to accomplish if given the chance, Matilda painted a picture of what they had already achieved. She cited Catherine Littlefield Greene who had initiated the idea of the cotton gin, an invention of which Eli Whitney took credit. She ended her speech with the rallying cry, “Onward! Let the truth prevail.” A prolific writer, Matilda sent off combative letters to newspapers signed with her initial: M. In her book Woman, Church and State, she argued that witches were merely inconvenient females and victims of unwarranted prosecution. The Russian author Leo Tolstoy responded to her work: “It proved a woman could think logically.”

Along with nine women, Matilda attempted to vote in Fayetteville for President Ulysses S. Grant, who was up for reelection. The suffragists favored his party as the Democrats opposed giving the vote to women. The official refused to allow Matilda to cast a ballot on the grounds she was married. Accordingly, she escorted a single woman to the polls; the result was the same. She described her third attempt, “Then I took down . . . war widows, whose husbands had left their bones to bleach on the field of battle, in defense of their country, and they, too, were refused, and so on through the whole nine.”

Matilda and Susan strategized a future trip to the polls. During this time, Susan stayed at the Gage home so often that Matilda’s children named an upstairs bedroom “the Susan B. Anthony Room.” For support, Susan took her sister and a friend to register to vote in a barbershop in Rochester, New York. When she succeeded, the act garnered national headlines. Matilda was not shocked at Susan’s arrest; she had often remarked that, in America, women were “born criminals.” During the trial, Matilda proved Susan’s staunchest supporter and railed that the United States was on trial, not Susan B. Anthony.

In 1886, the activist staged a protest at the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty. The New York State Suffrage Association had declared, “The Statue of Liberty is a gigantic lie, a travesty, and a mockery. It is the greatest sarcasm of the nineteenth century to represent liberty as a woman while not one single woman throughout the length and breadth of the Land is as yet in possession of political Liberty.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage were the triumvirate of the women’s movement until Matilda became too extreme for the Quaker Susan and the more conservative Elizabeth. They disagreed with Matilda’s radicalism, especially her insistence on the separation of church and state. Matilda took umbrage with the story of Adam and Eve which blamed women for original sin, death, and labor pains. Another source of friction was Matilda insisted on including women of color in the movement, an opinion the other two suffragettes did not share, likely because they felt it best to slay one hydra head at a time. Because of their divergent approaches, Susan and Elizabeth tried to excise Matilda from the women’s movement.

Another behavior against which Matilda jousted was the mistreatment of Native Americans. She admired matriarchal power within the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. The Wolf Clan of the Mohawk Nation offered her an honorary adoption and presented her with the name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi, “She who carries the sky.”

Matilda, mother to her children and her causes, was also the mother of Oz. Her daughter Maud had dropped out of Cornell (her class was the second to admit women) to marry L. Frank Baum. Although Matilda had been aghast at Maud preferring matrimony over education, she agreed to let the couple wed in Sunset View’s parlor. The Baums had five sons, and, at his mother-in-law’s urging, Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Matilda’s influence is apparent in the intrepid female protagonist, the witches, and Aunt Em (Em being an allusion to her initial, M).

The Matilda Joslyn Gage House

In 2000, the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation purchased Sunset View with the mission to transform it into a museum. For the endeavor, its members recruited Gloria Steinem who wrote, “Matilda was ahead of the women who were ahead of her time.” The center provides a hands-on experience where visitors interact with exhibits; for example, by leaving notes on Matilda’s writing desk, explaining how she had inspired them. The house consists of the rooms: Women’s Rights, the Family Parlor Oz, the Haudenosaunee, Religious Freedom, and the Underground Railroad. The gift shop offers souvenirs that commemorate Matilda’s speeches, writing, prints of her artwork, books concerning social justice, the Wizard of Oz, and other topics related to the principles advocated by the center. The museum counteracts Matilda’s unfair erasure as a cornerstone of the women’s rights movement and holds her up as a supreme suffragist.

On a visit to the Baums’ home in Chicago, at age seventy-one, Matilda passed away from a stroke. She had made plans for her death and a radical minister presided over her funeral. Although unusual for the time, Matilda had requested cremation, and a famous Theosophist spoke at her funeral. Maud took her mother’s ashes for burial in the Fayetteville Cemetery. The inscription on her tombstone is from Matilda’s own words: “There is a word sweeter than mother, home, or heaven; that word is liberty.”

A View from Her Window

Matilda and Henry had christened their home Sunset View because of the spectacular pink and lavender evening display over their Fayetteville home. However, another view from the same spot proved a pain-laden memory. Susan B. Anthony had been such a frequent visitor to the Gage home that she carved her name on the windowpane with a diamond ring—an etching that remains visible today. The inscription was a heartbreaking souvenir from the time when the three musketeers were one.

Nearby Attraction: The Women’s Rights National Historic Park, Seneca Falls, New York

There are no falls in Seneca Falls; however, it does have a three-acre park that witnessed the beginning of an American Revolution, and the birth of the women’s movement. The remnant of the old church is a sacred spot, a monument to its role in history. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s home is part of this historical site.

The two-story visitor center has an interactive exhibit that poses questions on sex discrimination, sexual harassment, and gender equality. There are life-size bronze statues of five of the women organizers. One is of Sojourner Truth alongside an excerpt from her speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” Near the chapel is the text of the Declaration of Sentiments engraved on a bronze wall, over which water flows.