Monkey's Uncle

“Make yourself at home, no one wishes you were there more than I do.” Mamie Fish

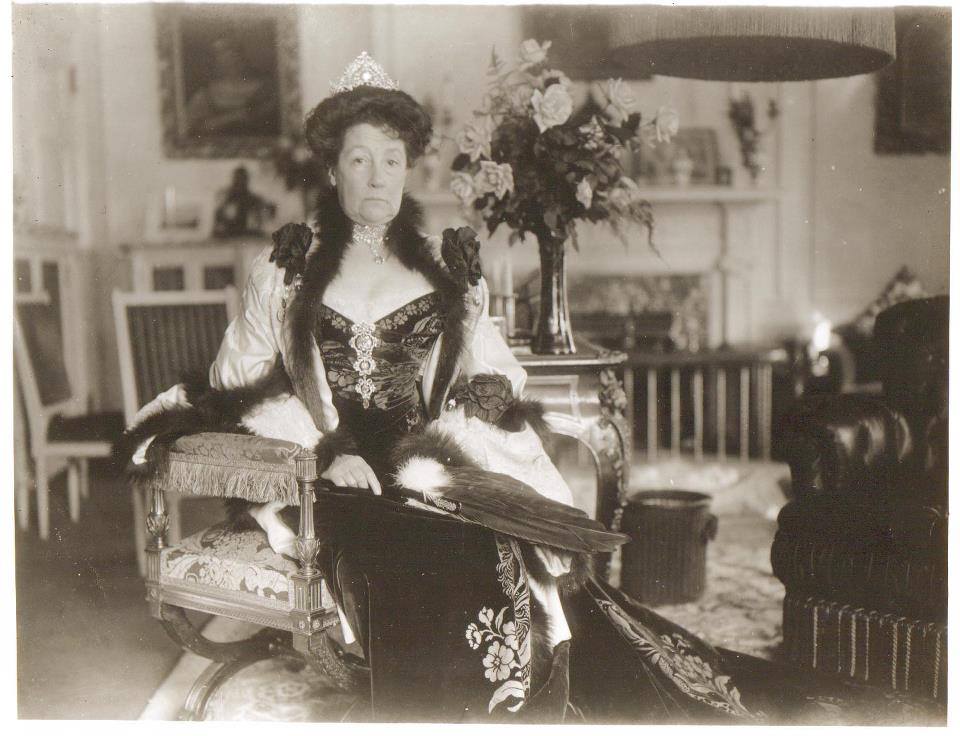

In 1979, Judy Chicago displayed “The Dinner Party” a sculpture that featured three forty-eight-foot-long tables-the gathering of notable women of Western civilization- from the ancient Greek lesbian poet Sappho to the first female physician, Elizabeth Blackwell. Despite Judy’s prodigious oeuvre, the work, (now in the Brooklyn Museum,) cemented the artist’s reputation. Similarly, Marion (Mamie) Fish’s dinner parties made her a member of the Gilded Age golden girls.

In the 1950s, the name Mamie conjured the image of First Lady Mamie Eisenhower who stood behind her man with the phrase, “I had a career. His name was Ike.” A horse of a far different color was Marion “Mamie” Graves Anthon from Staten Island. The first European colonists of New York, the Dutch, christened the borough “Staaten Eylandt” in honor of their country’s parliament. Her father, William Henry Anthon, was an acclaimed lawyer and legislator who had served as a general in the Civil War. His income provided la dolce vita for his wife, Sarah, and children George, Maria Theresa, and Mamie. The family lived in Grymes Hill, the upscale Gramercy Park enclave in New York City that afforded views of Brooklyn and Lower New York Bay. Although her father was an attorney, and her uncle, Professor Anthon, was a Columbia professor, Mamie was illiterate: education was a male domain.

The lavish lifestyle ended with William’s 1875 passing as money had always proven quicksilver in his hands. In straitened circumstances, the Anthons moved to Astoria whose factories belched toxic fumes. As Maria Teresa was not inclined towards matrimony, financial and social salvation lay with Mamie. However, her prospects seemed bleak as her braying laugh made one look around for a horse, and her face would never launch 1,000 ships. Nevertheless, the observation Becky Sharp made in Vanity Fair proved prescient, “And this I set down as a positive truth. A woman with fair opportunities, and without a positive hump, may marry whom she likes.” Just as Dolly Levi-the New York Jewish matchmaker in Hello. Dolly! had set her sights on Horace Vandergelder, Mamie did likewise with her youthful companion, Stuyvesant Fish. Popular parlance said he was born “with a silver spoon in his mouth big enough to be called a soup ladle.” Stuyvesant’s father, Hamilton Fish-so named after family friend Alexander Hamilton- had been a New York governor and the Secretary of State under President Ulysses S. Grant. The Fish family traced their lineage to the Dutch colonist Peter Stuyvesant, the last governor of New Amsterdam before it went by the name New York. While Stuyvesant could have courted Manhattan heiresses, Mamie made him laugh and scepters have been tossed aside for less. The smitten suitor sent Mamie flowers for her June 8th birthday. What prompted the romantic gesture was he had earlier escorted her to a dance and had shown up empty-handed. Unimpressed, Mamie told him that the wealthy Robert Goelet had not been guilty of such an omission. The couple embodied the principle of opposites attract: Stuyvesant was a man of few words, Mamie was a woman of many.

The 1876 Anthon-Fish wedding took place at the Church of the Transfiguration, (known as “the Little Church Around the Corner.’) The uxorious groom presented his wife a rose he later pressed in a book that he kept until his death, along with one of Mamie’s love letters. One of the handful of Gilded Age barons who did not sidestep his marital vows, Stuyvesant was so devoted that upon hearing her coughing at a party he asked if he could get anything for her throat. She answered: a necklace from Tiffany’s. Shortly afterwards, she was wearing her new gift. Mamie often remarked women did not need suffrage; they just needed a man like her husband. The couple were known as The Fish and, in a nod to her married name, for a surprise party she threw for herself, she hung fishbowls with goldfish from a golden tree.

The Hello, Dolly! lyric applicable to the twenty-two-year-old Mamie stated, “Hello, Dolly/Well, hello, Dolly/It’s so nice to have you back where you belong….” For a wedding present, Mamie’s in-laws gave the newlyweds a house in her former neighborhood of Gramercy Park. In their home, filled with the best of everything, they welcomed their first-born, Livingston, who died six months later. To ease their heartache were children Marian, Stuyvesant Junior, and Sidney. Mamie’s sister, who lived nearby in a home her brother-in-law had purchased, was a beloved Aunt Tess to her niece and nephews.

Never guilty of what Oscar Wilde deemed “the one unforgivable sin-that of being boring”-Mamie rose in the ranks of the Rhode Island hierarchy. An example of a bon mot occurred when Frederick Townsend Martin asked in a fund-raiser for the blind speech whether the audience would prefer to be deaf or blind. After Frederick shared the verdict had been in favor of blindness, the Dorothy Parker of the era quipped, “What? After hearing you talk for an hour?”

With coffers overflowing from Stuyvesant’s position as president of the Illinois Central Railroad and his staggering inheritance, the Fish family moved to a spectacular estate designed by renowned architect Stanford White. During a theater production at Madison Square Gardens, (designed by the architect,) in the belief Stanford was a sexual predator who had seduced his wife, Evelyn Nesbitt when she was sixteen, Henry shot him in view of the actors and the audience. Former New York City mayor, Michael Bloomberg, purchased the property for $45 million; it is currently the site of the Bloomberg Family Foundation.

Another Xanadu, Glenclyffe, a 480-acre estate perched near the bank of the Hudson River, had belonged to Senator Hamilton Fish. He had left the mansion to his oldest son, Nicholas Fish II, who had been the ambassador to Switzerland and Belgium. After Nicholas’s murder as he was leaving a saloon with two women of “dubious repute,” ownership passed to Stuyvesant. Deeming the 16,000 square property as claustrophobic, Mamie expanded it to 32,000 square feet. Post renovations, Glenclyffe included fifteen bedrooms and stables that could accommodate twenty-five carriages. However, Mamie came into her own as a Grande dame was through her Newport manse she christened Crossways after the two roads that crossed the exclusive township. The estate overlooked Bailey’s and Gooseberry Beach. The white, forty-room colonial style estate was ideal for entertaining: the dining-room seated eighty who her staff served with a 300-piece gold table service. When a snob disparagingly asked if the name of her home was Crosspatch, Mamie’s rejoinder was, “It’s a patch you will never cross.”

Caroline Schermerhorn Astor- who wielded the societal scepter in her palatial homes- threw soirees in which entertainment consisted of three- hour dinners where guests engaged in small talk. Desperate for a slice of the society pie, but unable to compete financially with Astors and Vanderbilts, Mamie found another route to the monied mountaintop. In lieu of lengthy dinners- waiters whisked away plates so quickly guests held onto them-she sent out invitations promising “something besides dinner.” And one of the things the hostess delivered were barbs in the same vein as those delivered by her contemporary, Oscar Wilde. When a group of ladies arrived in their newest Parisian couture, Mamie, remarked, “Here you all are, older faces and younger clothes.” And after Alva Belmont Vanderbilt accosted her and seethed, “I hear that you have been telling everyone that I look like a frog!” Mamie fired back, “No, no…not a frog! A toad, my pet, a toad!” On a visit to a woman who pointed out her home’s Rodin fountain she had imported from France Mamie sneered, “I have a trough exactly like it for my farm horses.”

For one of her stunt soirees, the partygoers dressed as characters from nursery rhymes; at another, she insisted guests spoke “baby talk.” An animal lover, for an indoor picnic, she once transformed her dining table into a pond complete with paddling baby ducks. On another occasion, she rented an elephant to whom guests fed peanuts. Mamie was part of the Guided Age’s love of exotic animals. Hunters killed millions of birds for fashion as women for plumage. Egret’s feathers became worth their weight in gold. To keep up with “the Jones,” for a casino evening she wore a gown whose pattern appeared as if she were sheathed in fish scales. The price tag was $2, 500- in contemporary currency: $95,000.

For another fete-in her belief that women preferred canines to men-she threw a Dog’s Dinner where she invited Newport’s top dogs. The Fish pooch stood out as he wore a $15,000 choker. (For her get- togethers, mining heiress Evelyn Walsh McLean’s Great Dane, Mike, sported the Hope Diamond affixed to his collar.) Butlers served the privileged four-footed of the Four Hundred stewed liver and rice, fricassee of bones, and specially prepared biscuits. A surfeit of food caused a dachshund to pass out.

Though the Fish guests declared the occasion “just the loveliest thing of the season, the Austin Daily Herald declared, “Could there be anything more ridiculous than this ‘dog dinner?’” Others likely not impressed with the upper echelon shenanigans were those on the other side of the gilded era’s coin-the poor who lived in tenements, the children who labored in factories, the masses whose lives were treadmill of subsistence. As society satirist Edith Wharton observed, “A frivolous society can acquire dramatic significance only through what its frivolity destroys.” And frivolity reigned in the era. To mark the close of the Newport season, Mamie threw a “Harvest Ball” that came with a price tag of $18,000-$676,000 in today’s dollars. Servants covered the lawns of Crossway with bales of hay and scarecrows, three oxen nibbled the grass, and guests donned farmer’s garb. Wearing a gold crown, “Good Queen Mamie” as the newspapers dubbed the hostess, ruled the pastoral setting. To make things interesting, she ordered the release of white mice that set the ladies screaming and running.

Even more over the top than the dog dinner was Mamie’s next party. To garner a buzz, she spread the word to the royal- mad Newport crowd that the Prince Del Drago would be her guest. When questioned if the prince was related to the Del Dragos of Rome, Henry “Harry” Lehr, Mamie’s partner in hijinks, responded, “They all belong to the same family, only the prince’s is a distant branch.” Mothers daydreamed of their daughter meeting and marrying the blueblood. Newport’s Court Jester, Harry, put out the word that the prince was no dour duke and was “inclined to be wild,” a trait exacerbated when he was in his cups. He warned, “Anything goes to his head, and then he is apt to behave rather badly.” The wealthy women spent the next few weeks practicing their curtsies. One can only imagine their faces when the wealthy Chicagoan, Joseph Leiter, arrived at the Ocean Drive mansion with the prince-attired in a tuxedo. The royal turned out to be their hostess’s pet monkey. No doubt the bejeweled dowagers ordered the butlers to fetch smelling salts. However, as Harry recalled, “After the first shock, the diners accepted Jocko- (the simian’s actual name) with good grace, and he, in turn, handled his fork and knife like a gentleman of the old school.” As Mrs. Lehr noted, “His manners compared favorably with some princes I have met.” The decorum came with an expiration date: despite prior warnings, the guests permitted the prince to imbibe, and the inebriated monkey swung from the chandelier while hurtling lightbulbs. Rather than being outraged, they pronounced the evening great fun, a sentiment not echoed by the press who ridiculed the event as a study in extravagance, in excess. Journalists sneered, “It is dreadful to think of distinguished foreigners coming over here and judging us by Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish’s entertainments. New York Society represents America in the eyes of the foreign world and we should behave with a becoming sense of dignity.” In France, citizens of Chartres mistakenly attributed the prank to local French church leader Henry Lehr. He made a statement to the Los Angeles Evening Post claiming “he had never dined with a monkey and was not that kind of man.”

The gag had originated on the Fish yacht when Mamie was bringing Jocko home. She had gone to a tailor to outfit him in dinner dress, and when he explained he did not make animal attire, he acquiesced at Mamie’s words, “Name your price, but start sewing-quickly.”

While Mamie had orchestrated her stunt to put herself on the Newport map, she might also have designed the party to puncture pretention. Had their grandfathers not fought in the Revolution to divest themselves from the royals and their world of titles and entitlement? Why was blood of blue still so enticing?

On her three-year European sojourn, she had encountered a Saxon prince who had looked down on the Fish fortune and informed her that he had been under the impression that Stuyvesant had “come from a fine family.” Her rejoinder, “Oh, yes, he does. But, you see, in America, it is not a disgrace to work. How much better it would be if those conditions prevailed in Europe! We in America would be spared so many titled nonentities.” While the Old-World aristocracy snubbed the American upstarts, work was not the New World’s four-letter word. That is why the families who had garnered their fortunes from oil and railroads resided at the pinnacle of society’s hierarchy. Along with frenemies Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Tessie Oelrichs, Mamie held court as the Grande dames of the Gilded Age. The three ladies were known as the Great Triumvirate. The Transcript Telegraph groused, “There are plenty of fish in the sea as good as Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish.” The Charlotte News wrote that given Mrs. Fish’s dress bills, “Mr. Fish could never have been the President of the United States.”

Alas, rain intrudes even in the grandest of castles, and Mamie’s reputation took a hit when she disparaged a First Lady. Stuyvesant had been friends with Theodore Roosevelt since childhood, and the two often went on bear hunts together. However, their wives, cut from far different clothes, did not see eye to eye. Edith Roosevelt had reservations regarding overspending on parties and re-wore the same gowns to White House affairs. In a press interview, Mamie disparaged Edith, “Mrs. Roosevelt dresses on $300 a year, and she looks it.” While society did not care about the Fish digs at the rich and the titled, they condemned her put-down of the First Lady.

A further blow to The Fish occurred when railroad executive Edward Henry Harriman accused Stuyvesant of defrauding the Illinois Central Railroad of $1 million dollars, ($33 million today.) The attack was partially born from Harriman’s hatred of Mamie who, after inviting his daughter Mary to a Newport party, had pronounced the young woman as dull and dismissed her from future events. When Stuyvesant learned of his dismissal, he throttled his replacement though it did not result in injury. The court of public opinion blamed his Missus for his downfall.

However, like the bop bag toy that bounces back every time it is hit, Mamie retained her hold as the hostest with the moistest. In her early sixties, Mamie remained a going concern. In the summer of 1912, she held a flower ball where guests dressed as their favorite bloom. The following year, she threw a Mother Goose extravaganza where attendees arrived as characters from nursey rhymes. The hostess was resplendent in the garb of the Fairy Queen. The age lost its gilded girl when, days before her thirty-ninth anniversary, Mamie passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage at Glenclyff. As always, her lifelong shadow, Stuyvesant, was by her side.

While ample information remains Mrs. Fish, what is not known is what she saw reflected in her gilded mirrors. Upon her passing, a friend described the socialite as someone who “sensed well the triviality in which she drowned her time, and her brash mirth concealed an ever more exasperated cry at the kind of life that went on around her.” If that assessment holds true, then Mamie’s favorite reminiscence could have been Prince Del Drago’s party in which she made Newport into a Monkey’s Uncle.