The Painted Bird

“I am as clear as the child unborn.”

The Rebecca Nurse Homestead (opened in 1909)

149 Pine Street, Danvers, Massachusetts

Witch-hunts are the thread that runs through the tapestry of history. The Romans fed the Christians to the lions; the Nazis consigned the Jews to the crematorium; the United States incarcerated the Japanese Americans. Three centuries ago, Salem targeted those the Puritans had decreed bore the mark of a witch. The importance of the Rebecca Nurse Homestead: it stands as sentry to the consequences of when hysteria and hatred triumph over humanity.

Witchy women have a prominent place in pockets of Massachusetts. Salem's police cars feature her image astride a broomstick, the high school football team bears the name Witches, the local newspaper uses her as its logo. A statue of Elizabeth Montgomery, star of the television series, Bewitched, depicts her astride a broom. In a 1970 episode filmed in Danvers, Samantha told her husband, Darren, “There were no real witches involved in the witch trials.” Her mother, Endora added, “It was only mortal prejudice and hysteria.” During Halloween, 100,000 tourists descend on the town where they snap cemetery selfies, salons provide ghoulish makeup and garish hairdos, souvenir shops sell witch-kitsch. Lost in the spell of the season are the victims who made the town synonymous with sinister.

New England’s link with infamy began in the winter of 1691. Tituba, a slave from Barbados, was baby-sitting the Reverend Samuel Parris’ nine-year-old daughter, Betty, and her eleven-year-old cousin, Abigail Williams. Since the Puritans frowned on all activities except those church-sanctioned, and as the winter made life even more confining, Tituba became the Salem Scheherazade. She read the children’s palms and spoke of voodoo, taboo topics in their Calvin community. Had Tituba been a better fortuneteller, she would have entertained the girls in a different fashion. The youngsters succumbed to “grievous fits”-they contorted and shouted gibberish. Members of the community gathered to sing psalms; Dr. William Griggs laid the blame at Satan’s door. As the current zeitgeist held that the devil could assume the forms of his followers, the community elders cast about for the perpetrators. The blame fell on Tituba, an easy target as she was a foreigner and a slave. Under pressure, Tituba “confessed” and implicated others. Her execution paved the way for nineteen more-fifteen women, four men and two dogs met a gruesome end. In the ensuing hysteria, children turned on their parents, spouses turned on one another.

The strange bedfellows of an ordinary woman and an extraordinary destiny began in 1621 with the birth of Rebecca in Yarmouth, England, the daughter of William Towne and Joanna Blessing. Desirous of escaping the religious intolerance of the Old World, the family set sail for the New. Rebecca married Francis Nurse, also an immigrant from Yarmouth. He bought a 300-acre farm in Salem where the devout churchgoers raised four sons and four daughters.

Rebecca would have remained a forgotten name on a headstone in a New England cemetery except for her unwittingly role in an era when the insane ruled the asylum. A committee of four men visited the Nurse’s home where the sickly, seventy-one-year-old Rebecca was on bed- rest. After learning her fellow citizens had accused her of causing them bodily harm through supernatural machinations, Rebecca questioned what she had done that God “should lay such an affliction on me in my old age.” The Putnam family, who had been involved in an acrimonious land dispute with Francis and Rebecca, had lodged the complaint. Sarah Cloyce, and Mary Easty, two of Rebecca’s sisters, rushed to her defense. For their pains, they likewise ended up running afoul of the authorities.

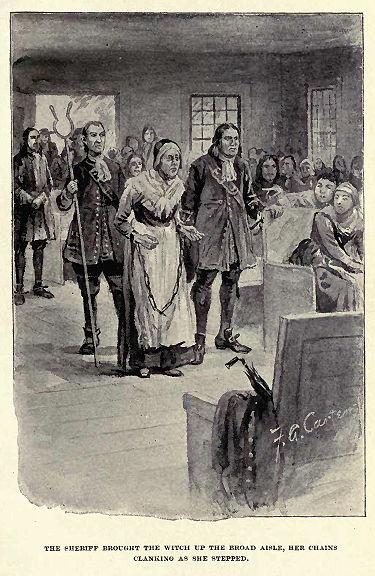

Rebecca Nurse stood before Judge Hathorne who stated, “It is awful to see your eye so dry when so many are wet.” Rebecca responded, “You do not know my heart. I never afflicted no child, never in my life. I am as clear as the child unborn.” The jury found her not guilty-the only such verdict. Immediately, Rebecca’s accusers began acting in a manner that indicated the need for an exorcist. The alarmed judges barraged her with a series of questions that she did not answer due to advanced age, hearing loss, and exhaustion from a physical examination that searched for “the Devil’s Mark.” Construing silence as a sign of guilt, a judge signed her death warrant. The court informed her that they would spare her life if she confessed to which she replied, “I cannot belie myself.” Her daughter, Sarah, futilely testified she had seen Goody Bibber prick her knees with pins while crying out blame. In 1692, the wife and mother of eight, who had lived an exemplary life, swung from a rope on Proctor’s Lodge at Gallows Hill. Buried in a shallow grave, her children surreptitiously claimed her body and gave her a Christian burial in the grounds of their home. Mary met the same fate as her sister; when the “hurly burly” of the annus horribilis ended nine months later, the jailers set Sarah free. After the execution of her sisters and her own date with the executioner, she and her family moved to Framingham, Massachusetts. Ironically, Salem derived its name from the Hebrew word for peace, “shalom.”

An exposé of the Salem Witch Trials, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote The Scarlet Letter that exposed religious hypocrisy. The author, the great-great-grandson of Judge Hathorne, changed the spelling of his surname to distance himself from his ancestor. A poem by Emily Dickinson entitled, “Witchcraft was hung, in history,” concludes that witchcraft is Around us,/every day.” Arthur Miller’s parable of the witch-hunt, The Crucible, shines a spotlight on the 1950s witch-hunt against the Communists. The Simpson’s Treehouse of Horror parodied the proceedings.

Perhaps the most damning denunciation of the mockery of justice is the Rebecca Nurse Homestead that is reached through a narrow path sandwiched between two nineteenth-century homes. Rebecca’s former residence is a large, clapboard structure topped with a brick chimney located at the end of a dirt lane bordered by thirty acres of fields and split-rail fences. The museum features three restored rooms, one that contains her spinning-wheel. Located on the premise is an authentic-looking reproduction of the first Salem Village Meeting House where the initial three victims faced their accusers: Tituba, Sarah Osborne, and Sarah Good. Producers of the 1985 television movie, Three Sovereigns for Sarah arranged for its construction. The show revolved around the three sisters who were plagued by the hounds of injustice; Vanessa Redgrave played the role of Sarah Cloyce. On the western edge of the property, nestled amongst trees, rests a monument situated directly over the grave of Rebecca. The inscription bears a poem, written for the occasion, by Hoosier author John Greenleaf Whittier.

“O, Christian martyr! Who for truth could die,

When all about thee owned the hideous lie!

The world, redeemed from superstition’s sway,

Is breathing freer for thy sake today.”

The other side of the stone states:

Accused of witchcraft she declared “I am innocent and God will clear my innocency.”

Once acquitted yet falsely condemned she suffered death July 19, 1692. In loving memory of her Christian character even then fully attested by forty of her neighbors. This monument is erected July 1885.”

A fourth author who wrote of the dangers of turning on one’s own was the Polish-born Jerzy Kosinski. In his 1965 novel, the boy-protagonist struggles to survive World War II in Eastern Europe. The title comes from a horror the boy witnessed: a man painted a bird and then set it free. The other birds from its flock viewed it as an interloper and tore it apart. The Rebecca Homestead bears the same message as the metaphor of The Painted Bird.

A View From Her Window:

If Rebecca had really been a witch, she would have looked from her window and obliterated the hate-filled faces of those who sealed her fate, and instead looked upon her posthumous resurrection. When her namesake museum invited people to send cards to commemorate her 400th birthday, the mail far exceeded their expectations. Many were from descendants; some of her famous ancestors: former presidential candidate Mitt Romney, Scrubs actor, Zach Braff, comedienne, Lucille Ball. She would have appreciated the apologies. In 1706, Ann Putnam delivered a confession to her church congregation that she regretted her baseless words; in 1712, the Salem Towne Church reversed her excommunication; in 1957, the state of Massachusetts issued a retraction. Rebecca Nurse still casts a spell.

NEARBY ATTRACTION: THE WITCHES MUSEUM:

In the front entrance of the museum, located in an 1840s church, has a statue of Roger Conant, the founder of Salem. Inside is another statue-of a devil with glowing red eyes. The museum reenacts the accusations, the trial, and the punishments to provide a sobering reminder of the town’s sordid past. The director admitted that the administrators are huge fans of the film, Hocus Pocus, set-in modern-day Salem that features a fictionalized version of the Salem Witch Museum.