Six Grandfathers (1941)

The genesis of social media occurred in 1844 when Samuel Morse sent the world’s first telegram with the words, “What hath God wrought?” The sentiment is echoed by the two million annual visions to Mt. Rushmore, the contemporary wonder of the world. However, many are not aware of the connection between the monolith and its namesake.

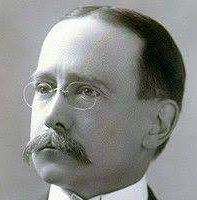

In 1884, Charles E. Rushmore, a New York attorney, was in the Black Hills of South Dakota to investigate mining claims. When he asked his local guide, Bill Challis, the name of one of its mountains, Bill responded, “It never had a name, but from now on we’ll call it Rushmore.”

Charles would have been gob smacked that his offhand query would lead to an association with a world-famous landmark, one that originated with an eccentric artist. Gutzon Borglum was born in Idaho in 1867, the son of Danish Mormon polygamists. In the early 1880s, he travelled in Europe where he befriended Auguste Rodin and became enamored of the sixty-six-foot Sphinx of Giza.

News of Borglum reached Caroline Helen Jemison Plane, the founder of the Atlanta chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who wanted a “shrine to the South” on Stone Mountain, Georgia. Borglum accepted her commission with the demand his stone canvass bear the likeness of Generals Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davies. The Ku Klux Klan embraced the proposal and served as a major source of funding. After a decade, his benefactors fired Borglum; in retaliation, he destroyed his model. He escaped Atlanta with the infuriated, white-obed former friends in pursuit.

Three decades later, historian Doane Robinson concocted a plan to lure tourists to South Dakota. His idea was to create a giant sculpture on Mt. Rushmore that would memorialize figures of the American West such as Lewis and Clark, Sacagawea, and Buffalo Bill. Borglum-whose ego was equal in size to his mountain-insisted the granite visages would hold Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln.

The equivalent of creating a contemporary Colossus of Rhodes began in 1927 with a ceremony presided over by President Coolidge who stated, “We have come here to dedicate a cornerstone laid by the hand of the Almighty.” The task seemed ephemeral: to impose man’s will on nature, based on a dream of a local historian, on a mountain named after an attorney from the East. When the modern Michelangelo passed away before Mr. Rushmore’s completion, his son, Lincoln, took over. America pronounced the monument the “shrine of Democracy.”

In contrast, the Lakota Sioux felt the Black Hills- that they refer to as “the heart of everything that is-” was theirs as evidenced by the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty that had deed it to them for perpetuity. Perpetuity only lasted until George Custer discovered gold and prospectors over ran their sacred ground. The Great Sioux War erupted, and with the Native American defeat an act of Congress forced them onto remote reservations. The Lakota pronounced the American government “wasin icu” that translates to “takes all the fat.” They were aghast tourists trampled over their ancestral graves to gaze on the men who had founded a way of life that had destroyed their own. When Challis had informed Rushmore the mountain had no name, he had been mistaken. The Lakota called it after the Earth, the sky, and the four directions: “Tunkasila Sakpe,” “The Six Grandfathers.”