Remain Silent (1966)

If you are a fan of television crime shows, or have been under arrest, you probably are familiar with the Miranda Warning. But what of the man who had the dubious distinction of having such a ruling named after him?

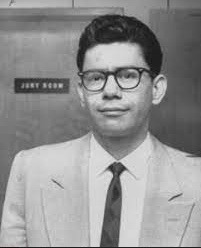

In 1968, Andy Warhol stated, “In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes.” The prediction proved prescient in the case of Ernesto Arturo Miranda, born in Mesa, California, in 1941, the fifth son of an immigrant housepainter from Sonora, Mexico. Childhood traumas were the death of his mother when he was six, and his father’s remarriage a year later to a despised stepmother. Dedicated to playing hooky, Ernesto’s formal education ended after the eighth grade. A stint in reform school for car theft did not lead to rehabilitation; he was again incarcerated for attempted rape and assault. His stint in the army ended after he received a dishonorable discharge after his incarceration for being a Peeping Tom. Miranda justified his voyeurism by explaining women left their shower curtains open because they wanted an audience.

Ernesto seemed to turn his life around when he met Twilia Hoffman, the mother of two, who did not have the money for a divorce. Together they had daughter Cleopatra and the family moved to Arizona where Miranda found a position as a laborer. Miranda’s brush with infamy began in 1963 when an eighteen-year-old woman told the police a stranger had raped her as she was returning home after her night shift at a movie theater. He had released her with the words, “Pray for me.” Her brother-in-law began picking her up from work, and one night she recognized her attacker’s car, a 1953 battered Packard, whose license plate revealed the vehicle belonged to Twilia Hoffman.

In custody in the basement interrogation room of the Phoenix Police Department, exhausted after a twelve-hour shift, Miranda wrote a confession that began with the words, “Seen a girl walking up street…” The court appointed him a lawyer, Alvin Moore, who had practiced little criminal law for the past sixteen years; he was unable to sway the jury of three women and nine men who returned a verdict of guilt after deliberating for five hours. A judge sentenced Miranda to a sentence of twenty-to-thirty years for rape.

At this juncture the ACLU was championing the cause of suspects deprived of their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. The organization chose to represent Miranda as his name was alphabetically before other potential clients such as Roy Stewart, Carl Westover, and Michael Vignera. In 1966, in the landmark Ernesto Miranda v. Arizona the Supreme Court, in a six to three decision, overturned his conviction. An immediate outcry arose that the ruling handcuffed the police in obtaining confessions; the opposing view was it was necessary to right the social inequity of America’s system of justice.

The court gave Miranda a new trial; however, even without his original confession, he was again found guilty. One reason was Talia, worried that her ex would seek visitation with their daughter, served as a witness who stated Ernesto had admitted he had been guilty of the rape.

In 1975, while out on parole, Ernest earned money by selling autographed Miranda cards for a $1.50. A month after his release, Ernesto drove his brother Ruben’s Thunderbird to La Amapola, a bar in a seedy Phoenix neighborhood, where a man stabbed him in a fight over a few dollars. The police read suspect, Fernando Rodriguez Zamora, his Miranda Rights.

Five words changed the course of legal history, ones that people should heed both in and out of custody: The right to remain silent.