No Black Sheep (1974)

In the 2008 film, Wall-E, a lonely robot on a post-apocalyptic Earth collects remnants from its vanished inhabitants, one of which is a Rubik’s Cube. Although millions are familiar with the classic puzzle, its reclusive creator, Erno Rubik, remains elusive.

The Rubik’s Cube can serve as a makeshift Rorschach Test: some players view it as a Modigliani art piece, some hurl it against the wall, some view it as a philosophical quest-to order haphazard colors into a pattern of symmetry. The classic began with Erno Rubik, born a month after D-Day, in the basement of a Budapest hospital that doubled as an air-raid shelter. His father, Erno, was an engineer who designed aerial gliders; his mother, Magdolna, was a poet. In Soviet-era Hungary, the family had no bank account, and Erno’s treat was a single-scoop ice-cream cone. After studying architecture at the Budapest University of Technology, Erno became a professor at the Budapest College of Applied Arts where his income was $200 a month.

While living with his mother, (his parents had divorced,) he tried to come up with a tool to help his students understand three-dimensional geometry. He put together eight wooden cubes, designing them with the capacity to move, then added colors to the various squares to make their placement more visible. Rubik took a month to return the cube to its original state, an achievement that left him with a “euphoric feeling of freedom.” No wonder: there are 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 and 43,252,003,274,489,855,999 of them are wrong.

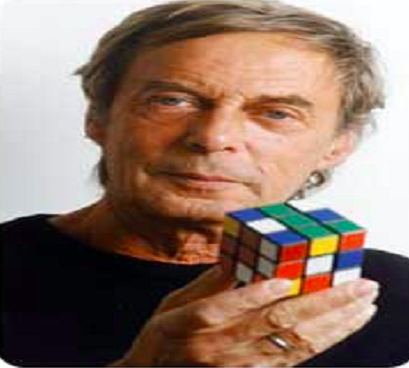

Once he cracked the code, Rubik peddled his idea to a firm, Politechnika, that manufactured it as “Buvös Kocka,” “Magic Cube.” At this juncture, Rubik met salesman Tibor Lacsi who described Erno as “terribly dressed, looking like a beggar, with a cheap Hungarian cigarette hanging out of his mouth.” However, he believed in the professor’s brainchild and proposed they market it on the other side of The Iron Curtain. The cube eventually reached borders beyond the Eastern bloc through Thomas Kremer, who had immigrated from Transylvania to America, had chanced upon it at the Nuremberg Toy Fair. Turned down by other companies, Ideal Toy Corporation-whose first success story was the teddy bear- added it to its roster under the name Rubik’s Cube. In 1980, the company brought the shy mathematician to act as a spokesperson at the New York Toy Fair to demonstrate the puzzle was indeed solvable. Rubikmania exploded, and the cube joined the august company of Barbie, Lego, and Slinky. Uncomfortable with the publicity, Rubik felt trapped by his Frankenstein, “I’m not the person who loves to be in the spotlight and so on and so forth….The cube loves attention; I don’t.”

The toy that had its genesis in wood took Erno’s life in an unimaginable direction. On an early television commercial, he challenged Hulk Hogan to solve the puzzle, earned a $100,000,000 fortune, and was the guest of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and Mayor Koch. In 1981, the Museum of Modern Art included the icon in its permanent collection, and in 1995, a jeweler made a functioning cube of 10-karat-gold, covered with gems, that carried a price tag of $ 2.5 million. For the Cube’s fortieth birthday, The National Toy Hall of Fame inducted it, (the Cube beat out contenders American Girl dolls, and My Little Pony, and the game, Operation,) the Empire State Building glowed with its colors, a Google Doodle made it into an interactive animation.

Erno lives in Budapest with his first wife, Ágnes, with whom he had two children, (he had two with his ex,) and has six grandchildren. When asked if it was burdensome having his name associated with an icon, Erno responded, “It’s not like being known as Jack the Ripper! The Cube is no black sheep.”