I Still Believe

“I want to go on living after my death.” – Anne Frank

The Anne Frank House (opened in 1960)

Prinsenghracht 263, Amsterdam, Holland

As Romeo walked the streets of Verona, he observed, “Here is much to do with hate but more with love.” The self-same words apply to an Amsterdam building that receives over a million annual visits. The hate emanated from the mustached madman of Berlin; the love stemmed from the shared devotion of the Frank family.

The world’s most famous diarist, Annelies Marie Frank, was born in 1929, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Her father, Otto, had received the Iron Cross during World War I. Otto worked in the family bank while his wife Edith raised daughters Margot and Anne. The girls affectionately called him Pim.

In the 1930s, twin shadows permeated the Frank’s home; the Depression shuttered Otto’s bank, and Chancellor Adolph Hitler blamed Germany’s economic ills on the Jews. With mounting dread, Edith and Oscar watched the Nazis parade through Frankfurt. To escape the descending noose, the family sought sanctuary in the Netherlands.

In their adopted homeland, Otto’s factory, Opekta Works, (that produced pectin used in the production of jam), located in an eighteenth-century canal building near the famous Westerkerk Church, proved lucrative, and his daughters adapted to life in Amsterdam. Margot was shy, unlike her extroverted sibling, who enjoyed figure skating, ping-pong, and jump rope. Friends nicknamed the loquacious Anne “Miss Quack Quack.” In a letter to her paternal grandmother in Switzerland, she wrote, “Yesterday I went out with Sanne, Hanneli and a boy. It was lots of fun. I have no lack of companionship as far as boys are concerned.”

In 1940, Germany launched Fall Gelb, an attack on the Netherlands that prompted the Dutch queen, Wilhelmina, and her cabinet to flee to London. She requested her subjects “to think of our Jewish compatriots.” Anti-Semitic ordinances began: “Voor Joden Verboden.” “Jews Prohibited” signs proliferated. The movie-mad Anne was devastated she could not attend the screening of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. A special gift for Anne’s thirteenth birthday was a red plaid diary with a metal clasp that led her to declare it “one of my nicest presents.” In her first entry, she wrote, “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you as I have never been able to confide in anyone. And I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support.” She addressed her diary as “Kitty” after Kitty Francken, a fictional character in Cissy van Marxveldt’s series, Joop ter Heul.

Further horrors followed: Jews had to wear a yellow Star of David marked Jood, soldiers smashed the windows of their businesses, and arrested those who attempted to flee. Due to Aryanization, Otto transferred control of his business to his Gentile colleague, Johannes Kleiman and his assets to Jan Gies. In vain, the desperate Otto sought visas for the United States. In 1942, when the sixteen-year-old Margot received a notice from the Gestapo with a summons for deportation, the Franks went into hiding. In a coded letter to his sister, Helene Elias, in Basel, Switzerland, Otto informed her they were going underground. Had he chosen Switzerland instead of Holland, the Franks would have been safe. The fateful decision plagued him for the remainder of his life.

The family’s refuge was in the achterhuis “backhouse, “of Ottos’s former office, its entrance obscured by a moveable bookcase. They shared their quarters with Hermann, Auguste, and Peter van Pels, as well as a dentist, Fritz Pfeffer. Anne’s entries were of the overwhelming boredom of life in seclusion, of the ever-constant fear of detection. She also shared with Kitty her feelings for Peter, noting that when they were alone together, “it’s as if a light goes on inside me.” Upon learning that a Radio Oranje broadcast from the Dutch government in exile in London had appealed to citizens to retain records of life under siege, Anne commenced writing in a more serious vein. She gave her narrative the title Het Achterhuis, (The Secret Annex).

After two years, the refugees’ spirits soared with news of the Allied invasion, hope that died with the Nazi raid of their hiding place. An unknown informant had turned them in; the going rate for each capture was $1.50. The prisoners ended up on the last train from Westerbork to Auschwitz. Authorities later transferred the sisters to Bergen- Belsen where they perished from typhus shortly before the British liberated the camp. The sole survivor, Otto, returned to Amsterdam where Miep Gies-who had been instrumental in keeping the factory’s occupants alive-presented him with his daughter’s journal. In a nod to Anne’s aspiration of becoming a writer, he arranged the 1947 publication of her diary, under the title, Het Achterhuis. Under the staggering statistic of six million victims, the eyewitness to the heart of darkness illustrated that the mass graves hid heartbreaking stories. Publishers have translated Anne’s account into seventy languages, and the book has sold thirty million copies, a figure close behind that of sales of the Bible.

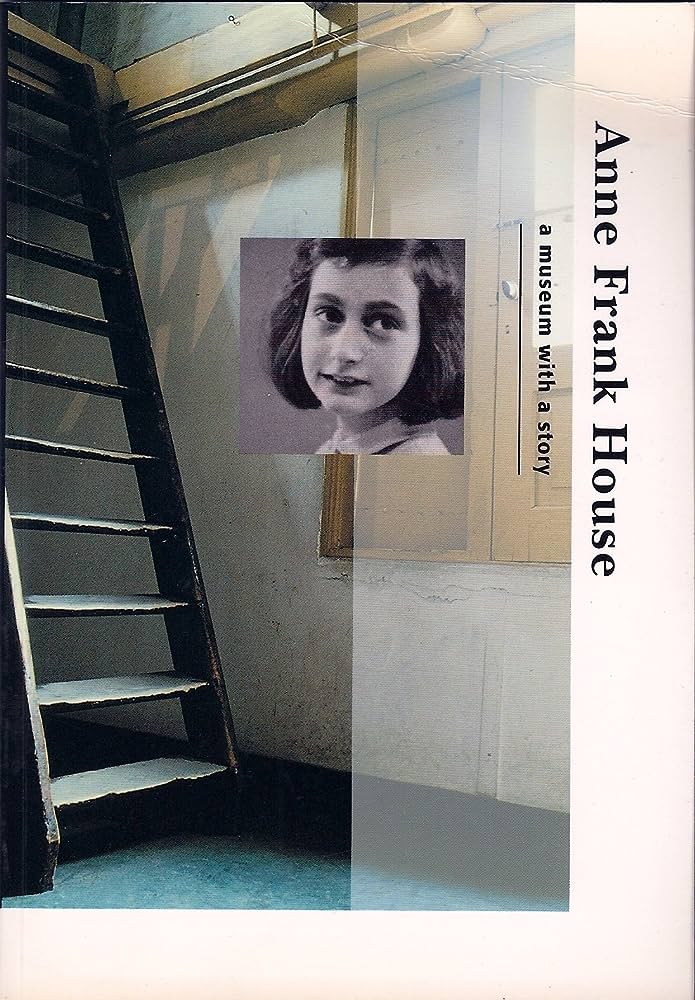

The museum that bears her name, and keeps alive Anne’s legacy, is on the site where she spent her final years. Climbing the steep stairs of the brick house presents a chilling reminder of a painful past. Eight decades ago, four Dutch officers, headed by SS-Hauptscharführer Karl Josef Silberbauer, forced their prey, at gunpoint, into a black van, the first time the prisoners had been outside in twenty-five months. Entering the building is extremely emotional as the experience confronts visitors with the horror that human beings can perpetuate on one another. What causes further heartache is what in ordinary circumstances would be inconsequential: pencil marks on a wall to chart the growth of three young people. Otto knew the children might never obtain their adult height. In Anne’s room, shared with Fritz to their mutual irritation, are faded pictures of actresses such as Greta Garbo, Deanna Durbin, and Ginger Rogers, as well as the young British princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret. The hiding place also had a map of Normandy and Brittany with pins on which Otto traced the advance of Allied troops.

The Anne Frank House is comprised of two museums. One is the secret annex that remains the same as it was the day of the arrests, a structure caught in a 1940s snow globe. Rather than refurnish it with authentic period pieces, Otto directed the rooms remain bare. After the capture of Jews in their homes, avaricious firms sold the furnishings and contents. Consequently, the only remaining object is a stove. The main part of the building is the enclave that had served as Otto’s factory that showcases exhibits of the Frank family, the Nazi occupation, of Bergen-Belsen.

The highlight is the display case that holds the museum’s most sacred object: the red plaid diary. The gift shop offers Anne’s book in a variety of languages including Hindi, Korean, and Persian. The English version came out in 1952 as Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. The quotation that offers a beam of light in the darkness of the Holocaust, are the haunting words, “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart….”

The View from Her Window:

From her window in the Secret Annex, Anne gazed upon a world she was unable to enter. Comfort derived from her view of a majestic chestnut tree; its changing colors served as a foliage calendar- the months spent in seclusion. In 1944, six months before her arrest, she confided to her diary, “From my favorite spot on the floor I look up at the blue-sky and the bare chestnut tree, on whose branches little raindrops shine, appearing like silver, and at the sea gulls and other birds as they glide on the wind. When I look outside right into the depth of nature and God, then I was happy, really happy.” Sixty years later, when the 150-year-old tree began to die, the Anne Frank Center took applications from institutions that wanted a sapling. The Center pre-approved three: the White House, the World Trade Center site, and the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. Of the thirty-four organizations that responded, the eleven winning bids received the three-feet high gifts as they showed “the consequences of intolerance and that includes racism, discrimination and hatred.” One of the saplings ended up in Arkansas where the Little Rock Nine, black students who integrated Central High School, under the protection of the National Guard.

Nearby Attraction: Van Gogh Museum

The museum has the largest collection of canvasses by painter Vincent van Gogh including masterpieces such as Sunflowers, The Potato Eaters, and The Bedroom. The main collection consists of four floors: the first one contains Vincent’s self-portraits; the last exhibit features paintings of artists inspired by the Dutch master. The museum also contains his personal letters, many written to his brother that began, “Dear Theo.”