Antonia's Ark (1908)

“You can never tell who your enemies are, or who to trust. Maybe that’s why I love animals so much.”

The modern zoo originated in 1907 when a German animal whisperer opened the eponymous Carl Hagenbeck Animal Park. Hans Augusto Rey, a frequent visitor, spent hours drawing monkeys he later immortalized in his literary creation, Curious George. A Polish zoo was also a curious place whose owner understood that those who emulate the three proverbial monkeys-see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil- are complicit in inhumanity.

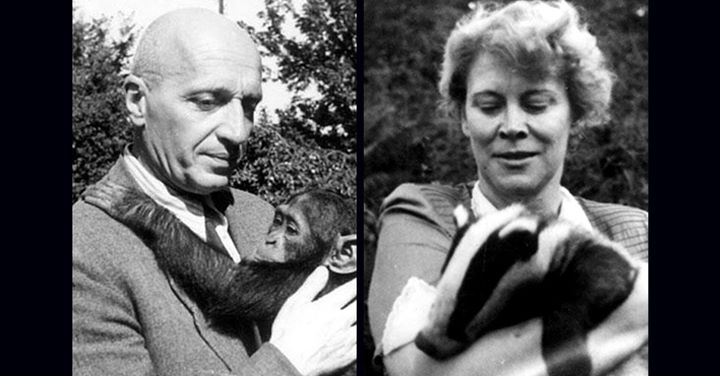

As the world abandoned its moral compass, the woman who firmly held on to her own was Antonina, raised as a strict Catholic by her father Antoni Erdman, a Polish railroad engineer based in St. Petersburg. Antonina was nine when the Bolsheviks killed her father and stepmother at the start of the Revolution. Her aunt took her to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where she studied classical piano, and later they left for Poland. Antonina worked as an archivist in Warsaw’s College of Agriculture where she met Jan Å»abiÅ„ski, a zoologist eleven years her senior. When a position for a zoo director arose, they seized the unique opportunity. In 1931, the couple married; the following year Antonina had son Ryszard, (RyÅ›,) christened after the Polish word for lynx. At one point, Antonina looked after three household toddlers learning to walk at the same time: her son, a lion cub, and chimpanzee. RyÅ›’s favorite pet was his badger who he took for walks with a leash and who used a potty. Antonina made her morning rounds on her bicycle accompanied by a usually tame camel and an ostrich. RyÅ› slept alongside Wicek, a lion cub, Balbina, a cat, and a revolving number of assorted animals.

Eden ended in 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland. In the Luftwaffe attack, a half-ton bomb rained death on their zoo, killing dozens of the animals trapped in their cages. To compound Armageddon, the ones who managed to escape stampeded into a Warsaw engulfed in flames. Not only were the Poles privy to the Nazi invaders goose-stepping into their capital, they also witnessed a Noah’s Ark of camels, llamas, ostriches, antelopes, foxes, wolves screeching through the streets. In the midst of the bedlam, Antonina stopped a stranger, “Have you seen a large badger?” The zookeepers eventually rounded up their four-footed.

Shortly afterwards, Lutz Heck, a zoologist, paid a visit; he knew the couple from before the war, and he was overly attentive to Antonina who reminded him of his first love who shared her blonde beauty. Lutz had become a Nazi who went on big-game hunts with Reich Marshall Hermann Goring and the Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels. Lutz ordered their prize specimens deported: the elephant, Tuzinka, to Königsberg, the camels to Hanover, the hippopotamus to Nuremberg. On New Year’s Eve, to ingratiate himself with the SS upper echelon, Heck arranged for a party at the Warsaw Zoo. Upon their arrival, Antonina grabbed RyÅ› and took him to his room to read his favorite book, Robinson Crusoe. However, there was no distracting her son from the sound of gunfire and the shrieks of animals in their death throes.

In shock at the depravity, Antonina wondered how such barbarity could happen in the twentieth century as evidenced when the German Governor of Poland declared, “I ask nothing of the Jews except that they disappear.” As a patriot, Jan joined the Polish Resistance where he took the code name Francis after Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals. His specialty was sabotaging German trains by jamming explosives into wheel bearings that ignited upon movement, and by slipping poison into Nazi sandwiches.

His wife was also committed to defying the murderers in their midst as she could not be like many of her fellow Poles who turned a blind eye to the plight of the Jews ensnared in the Warsaw Ghetto. Jan and Antonina decided to save as many Jews as they could, well aware that the price of doing so was execution that would leave their son an orphan. In the contingency of capture, the couple kept cyanide capsules on them at all times.

Comforted by the fact they knew how to handle dangerous animals, Jan and Antonina pulled the wool over the wolves’ eyes. Pretending to befriend the invaders, the Å»abiÅ„skis offered to raise pigs in order to provide them with meat. The subterfuge allowed Jan to enter the ghetto to gather refuse for hog feed; it also allowed him to smuggle desperate Jews out. While the Nazis depopulated the Ghetto, Jan and Antonina repopulated their zoo-this time with humans. The Å»abiÅ„skis’ hid their refugees in animal cages, in their basement, and in secret tunnels. Their guests who had Aryan features were passed via the underground to safer locations while those possessing Semitic appearance prayed to live out the war in hiding.

In one instance, Antonina decided to make the dark-haired Jews look more Aryan, and her guinea pigs were the Kenigsweins family. Using cotton balls soaked in diluted peroxide, she rubbed the concoctions on their heads that resulted in brassy red hair.

The fact that Heck who harbored an attraction to Antonina was a frequent visitor made the underground fraught with daily danger. In order to ward off suspicion with the family cook, housekeeper, and unwanted visitors, Antonina gave each of her “guests” an animal code name; for example, the sculptor Magdalena Gross was christened “starling” because Antonina imagined her as “flying from nest to nest to avoid capture.” Based on RyÅ› comment that the Kenigsweins’ dyed hair made them look like squirrels, they took on the code name squirrels. RyÅ› found it strange that his animals bore human names, and the strangers in hiding went by animal names. In a home fraught with more dangers than Robinson Crusoe ever faced, RyÅ› knew if he let the truth of the underground slip out, his parents would be killed. He stopped playing with school friends and confided his secrets only to MoryÅ›, his pet pig. A never-ending trauma for the child was when a German soldier dragged MoryÅ› to be butchered for meat.

The residents referred to their sanctuary as “The House Under a Crazy Star.” Feeding the escapees, sometimes as many of fifty were in residence, proved problematic. On one occasion when German soldiers shot the flocks of crows, Antonina gathered their corpses and her “four and twenty blackbirds” were baked into a pie that she passed off as pheasant pie. Although it was not “a dainty dish to set before the king,” it was a welcome treat. Another code was when Germans were at the door, Antonina rushed to her piano where she pounded out the chords of Jacques Offenbach’s “Go, go got to Crete!” from La Belle Helene. Because of all the brushes with the Grim Reaper, one of their guests remarked that they must live under the influence of a lucky star, not just a crazy one.

A fellow freedom fighter, Irena Sandler, code name Jolanta, had dedicated herself to smuggling children from the ghetto in coffins and boxes and placed them with Catholic families or in orphanages. The children had to assume Christian names so Irena wrote their real ones on slips of papers that she buried in jars in the hope they could be reunited with parents who survived the war. The Gestapo ended up capturing her, and they subjected her to torture in Pawiak Prison. Irena escaped with the help of the Underground and became one of the Å»abiÅ„skis’ esteemed visitors.

In the spring of 1943, Heinrich Himmler determined to liquidate the Warsaw Ghetto as a birthday present for the Fuhrer. Dedicated heart and soul to the mustachioed madman, he once told a friend, “Believe me, if Hitler were to say I should shoot my mother, I would do it and be proud of his confidence.” What Himmler planned as a gift-wrapped massacre became known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising where the surviving Jews decided to go out in a blaze of resistance. When the Germans set fire to the Ghetto, many died in the flames, committed suicide, or surrendered. A few managed to escape, and underground newspapers called upon Christian Poles to shelter the escapees. The Å»abiÅ„skis’ opened their doors, though Antonina had her hands more full than usual with the birth of her daughter Teresa. As his own act of retaliation, RyÅ› and another boy painted a towel with big red letters: “Hitler kaput!” that they planned to hang over the main gate of the zoo. Jan punished his saboteur-in-the-making with a spanking.

In 1944, as the tide of war blew against the Nazis, the Poles decided to stage a counterattack. Jan bid farewell to his mother, wife, and two children; before he left, he handed Antonina a tin can that held a loaded revolver in case the Germans arrived. The heavy burden of caring for RyÅ›, his four-week-old sister, and those hiding in the House Under a Crazy Star often led Antonina into bouts of depression.

After the news of the Polish Uprising reached Hitler, he ordered Himmler to bulldoze Poland as a warning to the rest of Europe. As Stukas rained death on the city, two SS men barged into the Å»abiÅ„ski home shouting, “Alles raus!” Ordering the family outside with hands raised in surrender, Antonina could only lift one as she was holding Teresa. Although paralyzed with fear, Antonina pleaded in German how noble they were, how she admired their ancient culture. The guns did not lower. A soldier ordered RyÅ› to go behind the shed, and when he disappeared from view, a single gunshot rang out. RyÅ› appeared a few moments later with their chicken, Kuba, dripping blood. One of the soldiers smirked, “We’ve played such a funny joke!”

At her lowest moment during the occupation, Antonina wrote in her diary of the Nazi nightmare that it was, “a sort of hibernation of the spirit, when ideas, knowledge, science, enthusiasm for work, understanding and love-all accumulate inside where nobody can take them from us.” The spiritual hibernation ended with the defeat of the Third Reich and Jan returned from a prisoner-of-war camp.

The following year, the Å»abiÅ„skis began the painstaking process of rebuilding their ravaged zoo that reopened in 1949 with some of the original animals. However, with the communist takeover of Poland, and the back-to-back ravages of Nazism and Stalinism, two years later Jan resigned as director. In her later years, Antonina wrote several children’s books, always from the perspective of animals. Antonina’s dream of a Warsaw Spring-and a reborn zoo-came to pass after the fall of communism; Antonina did not live to see it as she passed away in 1971. Before Jan died three years later, he told a reporter about how “a timid housewife” mustered the strength to stand up to the butchers. He explained that she was able to do so because “From time to time she seemed to shed her own human traits and become a panther or hyena, able to adopt their fighting instinct, she arose as a fearless defender.” The Warsaw Zoo is once again open, and the Å»abiÅ„ski home is now a museum. For her role in saving her beloved animals from the twentieth-century flood, her story can be expressed as Antonina’s Ark.