Cain and Abel (1949)

Urban legend holds that Adidas is an acronym for “All Day I Dream About Sports,” or “All Day I Dream About Soccer,” or “All Day I Dream About Sex.” The assumptions are incorrect. The shoe emporium originated with a feud between two Bavarian brothers.

Little do people imagine as they lace up their Adidas that they are wearing footwear that encompassed two world wars and a historic Olympic game. The story began in a German village, Herzogenaurach, divided by the Aurach River. Christopher Dassler worked as a cobbler; his wife, Paulina, supplemented their income by taking in laundry. Her sons delivered the clean clothes which earned them the name “the laundry boys.”

The modern world caught up with the medieval town with the outbreak of World War I. When Adolph and Rudolph returned from the trenches of Flanders, the Treaty of Versailles placed an economic noose on the Fatherland, thereby making Paulina’s services no longer affordable. In the empty room, Adolph fashioned sporting shoes made from army helmets and parachutes. He also invented the first spiked shoes with nails forged by a blacksmith. Rudolph acted as salesman; in 1924, they established the Gebrüder Dassler Sportschuhfabrik, the first athletic company.

In 1933, the Dassler brothers joined the Nazi party. Although it flew in the face of the Third Reich’s advocacy of Aryanism, Adolph persuaded Hitler’s nemesis, African American Jesse Owens, to wear Adidas for the Berlin Olympics. After the American sprinter won four gold medals, sport enthusiasts beat a path to their factory’s door.

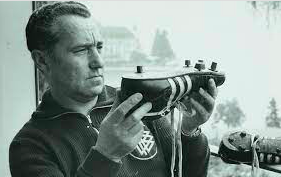

World War II served as a spike in the heart of Gebrüder Dassler Sportschuhfabrik. Adi remained in Germany in order to run the factory that produced Wehrmacht weapons while Rudolph held a position in the Lodz Ghetto in Poland. With Germany’s defeat, the Allies prosecuted Rudolph for his involvement in the Third Reich and imprisoned him for a year in an internment camp in Hammelburg. When he learned that his brother was selling shoes to the occupying American forces stationed in nearby Nuremberg, Rudolph was convinced his younger brother had set him up in order to assume sole ownership of their business. Herzogenaurach became the West Side Story version of “the Sharks” and “the Jets-” just in Lederhosen. The brothers disbanded their company and Adolph established his own that he christened after his nickname, Adi, and the first three letters of Dassler: Adidas. On the other side of town, Rudi founded his rival Ruda, that he derived from the first two letters of his first and last name. He later changed it to Puma. The Aurach River became a liquid Berlin Wall; the villagers’ sided with one of the two rival fiefdoms and only socialized with those who wore the Adidas stripes or the Puma feline logo. In 1974, a priest asked Adi to visit his dying brother; he refused to cross the river. The Dasslers graves are located at the opposite ends of the town cemetery.

The enterprise that began in a laundry room went on to capture markets in 150 countries and generate billion-dollar annual incomes. The shoes were also part of iconic moments: a photograph from the 1968 Mexican Olympics shows John Carlos, who had worn Puma, making the Black Power salute. In 1970, during the World Cup, Pele tied the laces of his Adidas.

On display in the Adidas Museum in Herzogenenaurach are iconic photographers: Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Muhammad Ali at a 1976 boxing match, Nadia Comaneci at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. Perhaps the most poignant is the black and white photograph of children Adi and Rudi playing ice-hockey on the frozen Aurach River, the time before they transformed to the Bavarian Cain and Abel.