Both Sides Now (1893)

Ferris Wheels serve as Proustian madeleines that deliver a heady dose of nostalgia. The sky- ride calls back yesteryear when there was nothing so wrong that a candy floss could not make right. For the magic memories we can thank its creator, George Ferris, Jr.

The World’s Columbian Exposition, (The Chicago World’s Fair) commemorated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ landing in America. Chicago pulled out all stops to make the event so spectacular that it would alter its perception of a city that preferred “butchered hogs to Beethoven.” The person who helped with the endeavor by reinventing the wheel.

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. was born on Valentine’s Day, 1859, in Illinois; at age five, during the Civil War, the family relocated to a ranch in Carson City, Nevada. Childhood was a Tom Sawyer idyll where a favorite past-time was lying on the banks of a nearby river watching a water wheel turn. Setting his sights on engineering, George received his degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. By the late 1800s, George opened his own Pittsburg-based company, G.W.G. Ferris & Co that specialized in trains and bridges. He also became the husband of Margaret Ann Beatty from Canton, Ohio.

In 1890, eminent architect, Daniel Burnham, needed to transform a nondescript square mile of Chicago into a magnet that would attract millions. Burnham challenged the world’s most eminent engineers to come up with an idea that would rival the landmark created a year before in the Exposition Universelle in Paris that celebrated the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution: the wrought iron structure that kissed the clouds: the Eiffel Tower. He instructed, “Make no little plans.” Gustave Eiffel submitted an entry for a taller tower; however, the exposition required “something novel, original, daring and unique.”

The thirty-three-year-old engineer from Pittsburg, whose company was inspecting the steel earmarked for the fair, determined he would “out-Eiffel Eiffel.” At a restaurant, George drew a sketch on a gravy-stained napkin that envisioned fairgoers taken to a height that would surpass the recently erected Statue of Liberty. The Exposition Committee pronounced him “a crackpot.” George had faith in his wheel; Margaret Ann had faith in her husband.

The fairgrounds of the Chicago World’s Fair, inaugurated by President Grover Cleveland, garnered the nickname “The White City” as all its structures all bore that color. One of the main attractions was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. The Exposition also debuted novelties such as Cracker Jacks, Aunt Jemima pancake mix, the zipper, Wrigley’s Chewing Gum, and electricity. But the crown jewel of the event was Ferris’ wheel.

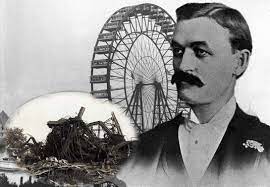

The star of the show held over a thousand passengers per ride, was of twenty minutes duration, and cost fifty cents. However, when the fairground gates closed for the final time, Ferris, embroiled in wheel-related lawsuits, lost his wealth and his fair-weather wife. Three years later, George died alone from typhoid fever; no one claimed his ashes.

Unlike the Eiffel Tower that remains the symbol of France, a wrecking company bought the wheel and sold it to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Two years later, workers dynamited it into a twisted mound of scrap metal thereby ending George’s dream of his creation becoming an immortal American icon. However, seventy-three years later, Joni Mitchell immortalized his namesake in her song, Both Sides Now, “Moons and Junes and Ferris wheels….”