Eureka! Penguin Books

Revolutions have made deep inroads on the face of history: the French, American, and Russian Revolutions irrevocably altered the world. However, there was another type of upheaval, equally ideological, but far less bloody, that led not to political change but to revolution. Moreover, in the process, a bird once only indigenous to the Arctic became ubiquitous throughout the world.

At Bristol Grammar School Allen Williams was an indifferent student who would never have had a life intimately involved with books except for an event that altered his destiny. When Allen was a teenager, his uncle, John Lane, told the Williams family that as he was childless, he would look upon Allen as his surrogate son if he agreed to change his surname to Lane. Not only did Allen agree to this the whole family changed their name as well. Excited to leave school where he had only achieved mediocrity, Allen Lane left home at age sixteen to seek his fortune in London.

Allen began his publishing apprenticeship at the Bodley House publishing house, where John Lane held the reins firmly in his hands; eschewing nepotism, he started his nephew off at the bottom rung. Bodley Head had amongst its roster of high-profile clients Oscar Wilde; however, no love was lost, or ever found for that matter, between John Lane and Wilde. Lane was furious with the writer because he had seduced an office boy from Bodley Head; Oscar showed his reciprocal contempt by calling a manservant Lane in The Importance of Being Earnest.

Because of Lane’s connections, he had the privilege of meeting authors such as Bernard Shaw and Anatole France. As a member of a horse- riding club, he attended a gala at Buckingham Palace in full equestrian attire. His spurs locked together and, when summoned to meet the king, he glided forward in a gait more suited to a slow- motion ice-skater.

In 1923, John Lane died, and his will stipulated that the Bodley Head torch would be left to his young heir apparent. The first major butting of the heads in the company occurred over the banning of Ulysses; the threat of prosecution made it a literary hot potato. When Allen decided that the Bodley Head was going to publish it, his Board of Directors was equally committed that it would not. Its publication proved both a commercial and literary victory.

In 1934, after a weekend in Devon visiting Agatha Christie, Allen found himself, bookless, waiting for a train. Desperate for reading material, he discovered that he could not find anything to read at the station bookstall except pulp paperbacks and popular magazines. It was then that Allen had his eureka moment: he realized his mission, for both missionary and mercenary reasons, would be to satiate the public’s appetite for inexpensive, quality books. At that time, the only source for reading contemporary authors was through hard-back editions, which were so expensive they were out of reach for the common man. Allen immediately grasped there was a huge need for affordable, quality literature, which would mean distributing the works as paperbacks. He felt that they should be priced the same as a pack of cigarettes and small enough to slip into a pocket. He later explained, “A man who may be poor in money is not necessarily poor in intellectual qualities.”

His colleagues not only did not share his enthusiasm but were dead set against it; they felt that literature was the realm of the moneyed, not the masses. Allen, realizing he could march to no other drummer than his own, decided to forfeit his inheritance and leave his uncle’s press.

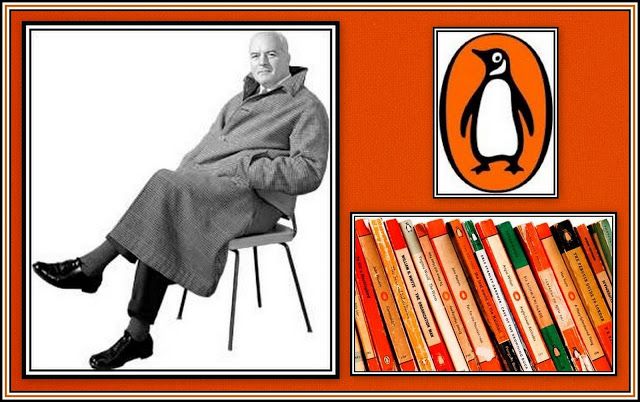

With his brothers and £100, Allen set out to found his own publishing enterprise; he rented space in the crypt of Holy Trinity Church and arranged for a fairground slide to receive deliveries from the street above. Once settled in, he needed to christen his company. When his secretary suggested the name Penguin, Allen Lane latched onto it; he felt that it was “dignified but flippant.” The twenty-two-year-old Edward Young, who had been lured away from Bodley Head to design dust jackets, was immediately dispatched to the zoo in Regents Park for inspiration for a logo.

Lane decided that he wanted his books to be taken seriously; consequently, they would not have any pictures on their covers because that would have been too similar to the lurid current paperbacks then sold. Once he had the place, the name, and the design, all Allen needed was customers.

Customers, however, proved to be a sticking point in Allen’s plan, as many booksellers refused to stock the paperbacks. Allen felt he was going to have to admit defeat when serendipity stepped in.

The buyer for the chain store Woolworth’s, told Allen that he did not like books without pictures on their covers, but at that moment, the buyer’s wife showed interest in the product, and her husband agreed to carry a few dozen copies for each of the London stores. Due to their success, Woolworth’s placed another order a few weeks later, this time for over 63,000 copies. The seemingly flightless bird was flying off the shelves.

The “dignified but flippant” publisher became as much a British national institution as the BBC, the Old Vic. and the Rolls- Royce. Lane had become the modern Gutenberg. Early editorial meetings were held in a favorite Spanish restaurant, The Barcelona, with plenty of wine to accompany them. One visitor was shocked to discover an editorial meeting taking place on a rowboat, the staff dipping into gin as steadily as the oars did into the water. Allen Lane became a millionaire and the prophet of a publishing revolution.

In 1941, Allen was in Cambridge for an editorial meeting when he attended a party. He was standing by himself as his social skills did not match his entrepreneurial ones. One of the guests, Lettice Orr, noticed the impressive, meticulously tweed-clad publisher, and a week later Allen invited her to stay at Silverbeck, the mansion that Penguin had built. The estate was flanked by a huge wrought- iron gate, either side decorated with his trademark birds. They were married later that year, a contingent of cardboard Penguins forming a guard of honor outside the church. They had three daughters, and Allen proved every inch the doting father. Further fame followed with his knighthood; on this Buckingham Palace visit he did so without spurs.

In 1960, Lane once again became the champion of free speech when he decided that Penguin would publish the unexpurgated version of D.H. Lawrence’s steamy Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The trial for obscenity was decided by Mervyn Griffith-Jones, who, when asked how he would decide whether to prosecute, answered, “I’ll put my feet up on the desk and start reading. If I get an erection, we prosecute.” Lane was ultimately acquitted, and sales soared to three million. The second edition of the novel contained a dedication from Penguin publishers to the intrepid jurors.

Although fortune smiled on Lane on the professional front, his home life did not fare as well; by the mid-1950s, his marriage was unraveling. This was partially due to Lane’s coldness. As he himself remarked, even those he loved “could only get so close, but no closer.”

In 1965, chief editor Tony Godwin bought a book titled, perhaps symbolically, Massacre, which Lane thought unworthy of Penguin’s imprint. Allen, along with some long-serving, loyal members of the warehouse staff, loaded all the offending books from the Penguin storeroom into a van and burned them. He then sacked Godwin and retained control of his company.

In 1970, Sir Allen Lane finally met an opponent he could not knock down; he passed away from bowel cancer, and his ashes were interred, alongside his Uncle John’s and his parents’, in the graveyard of an ancient monastery on the North Devon coast. Tributes flooded in from all over the literary world; obituaries were long and laudatory. The most heartfelt tribute came from Allen’s son-in-law, Clare’s husband, Michael Morpurgo, “AL’s epitaph might be the same as Christopher Wren’s, ‘If you seek his monument, look around you.’ He was kind and ruthless, charming and chilling, generous and mean, a complex man, never easy to understand. But heroes should be judged, I think, by what they achieve. It should be added, as a footnote but an important one, that Allen Lane is also my wife’s great hero. Being her father, I suppose, that’s hardly surprising.”

Sir Allen Lane, the literary emperor penguin, hatched his brainchild in a British train station. In turn, it gave birth to a twentieth- century revolution waged with ink rather than blood and resulted in the democratization of knowledge.

~In 1937, Penguin moved its office from its crypt to Middlesex; the property cost £2,000, plus an additional £200 for the crop of cabbages that were growing there. The staff had to pick its way through the cabbages, which Lane marketed. It is opposite to what is now Heathrow Airport. Allen’s father laid the cornerstone of the new building.

~An annual Penguin festival takes place in Bristol (May 18-21), the city of Allen’s birth.

~Allen’s brother John died in the North Africa Landings in 1942. In 1955, his brother Richard tool over Penguin in Australia. (He made a huge mistake when he sold his personal shares.)

~Penguin continues Allen Lane’s tradition of championing free speech with titles such as Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. The company also released Michael Moore’s Stupid White Men after attempts in the U.S. to ban it.