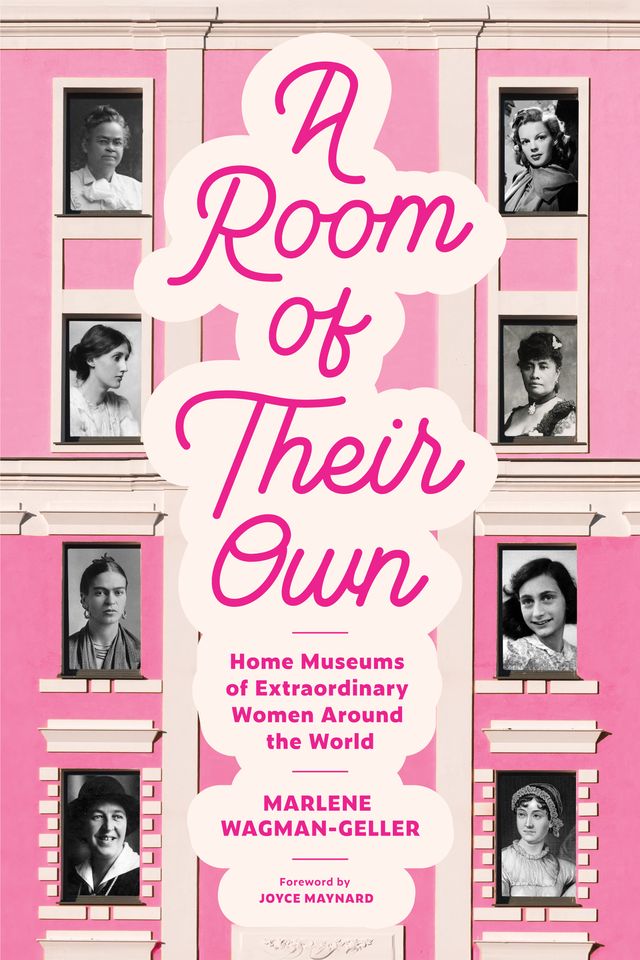

Preface: A Room of Their Own: Women's Home Museums Revealed

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story.” –Homer

The word museum originated from the ancient Greek word that denoted “place of the muses.” The nine Muses were the offspring of Zeus–who wasn’t?–and Mnemosyne, the Goddess of Memory. Indeed, museums are the repositories of memories, of ancient civilization, of the apogee of artistry.

Everyone has heard of the major museums whose stories are as intriguing as the works they display: Paris’s Louvre, London’s National Gallery, New York’s the Metropolitan. Between the three iconic institutions, twenty million visitors walk their halls, approximately the same number as people living in Beijing. But what about the galleries that do not display canvasses that bear the signatures of The Old Masters such as Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Picasso?

Curiosity about the daily lives of the famous draws us to the places they called home. A Room of Their Own is an investigation into museums, (sometimes referred to as memory museums), dedicated to fascinating women whose lives left indelible fingerprints on history. As these landmarks are situated in their subjects’ homes, rather than passively gazing at paintings with accompanying brass plaques, visitors undergo a more intimate experience. Upon entering their thresholds, one encounters a three-dimensional diary with artifacts that comprised their everyday lives: furniture, photographs, and letters. Even the most mundane of objects takes on a magical realism, as they were the possessions of ladies of legend. The rooms where its residents lived serve as a confessional; there they laughed, mourned, created, (and, in Lizzie Borden’s case, killed). For those with a nod to the mystical, the ghostly chatelaines serve as guides. House-museums are Piped-Pipers to the curious. Walking where historic figures once tread presents the opportunity to hear the scratching of Emily Brontë’s quill in her Haworth Parsonage, hear an aria in Edith Piaf’s Parisienne apartment, imagine the iridescent blue of radium that doubled as Marie Curie’s nightlight. Whether the homes be humble or haute, all double as biographer. Betsy Ross’s miniscule dwelling in Philadelphia, and Marjorie Merriweather Post’s opulent estate, Hillwood in Washington, D. C., are equally compelling. The closest we can come to time travel–the closest we can come to a séance–is entering what was once the ladies’ private place. Their spirits hover over the heads of their guests and whisper, “We were here. We mattered.”

Where one travels on vacation is as autobiographically revealing as home décor. Some ski the slopes of Switzerland; some lather suntan lotion on Hawaii beaches; those with an adventurous-slash-suicidal bent run with the bulls in Pamplona. But for those who enjoy communing with the ghosts of yesteryear, the best way to do so is head to the locales that helped define those who went before. The rarified atmosphere retains the memory of the writers who searched for the mot juste, arm-wrestled their muse. In Florence, we can enter Elizabeth Barret Browning’s bedroom where she penned her poems; in Nairobi, we can visit the farm and country that inspired Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa; in Wellington, we can scrutinize Katherine Mansfield’s belongings.

Although most women’s home museums are situated in the United States, other countries also have shrines to the ladies who left legacies: England, Canada, Mexico, Holland, Poland, Germany, Switzerland, New Zealand, France, the Dominican Republic, and Kenya. When visiting these locales, these are must see landmarks.

A further method of obtaining a peephole into the past is by gazing out the widows of historic homes; each chapter ends with The Window of Her World. Geographical locale and gardens play an integral part of one’s psychological DNA. When Isabella Stewart Gardner looked out her window, her view was of the courtyard that housed gems of civilization such as a Renaissance Venetian canal-scape, an ancient Roman sculpture garden, and a medieval European cloister. Surrounding the treasures are rotating flower displays–depending on the month–orchids in the winter, hanging nasturtiums in the spring. Isabella’s mantra: “the best of everything.”

In the Coyoacán suburb of Mexico City, Frida Kahlo lived in the Casa Azul whose backyard was as colorful as the walls of her home. She filled her garden with her menagerie of pets–her surrogate children. The makeshift zoo held monkeys, a deer, and several Xoloitzcuintli, (hairless dogs). From her courtyard, her tequila imbibing parrot squawked, “No me pasa la cruda;” “the English version, I can’t get over this hangover.” Visits to the Kahlos invariably proved a boredom-buster.

By touring storied addresses, tourists experience off-the-beaten path destinations that double as magical mystery tours. Whether we love or loathe the women, walking in their shoes makes for a better understanding of their legacy. While traditional galleries allow us to gaze upon well-known canvasses, the thrill is nevertheless a passive experience. In contrast, stepping over the threshold of a famed resident allows for an up close and personal encounter.

While some view museums as a repository for the dustbins of the past, watched over by guards who prefer patrons adopt the code of omertà, galleries can provide high drama. One of the greatest whodunnits? occurred in Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. In 1990, two thieves, dressed as police officers, tied up the guards and made off with Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Manet masterpieces. The stolen items represent a $500 million loss and despite a ten-million-dollar reward, the theft remains the greatest unsolved mystery of the art world. When gazing at the empty frames that once held storied canvases, one can hear Isabella’s cries emanating from the Mount Auburn Cemetery at the desecration of her former home.

Historical homes oftentimes serve as an essential backdrop to their owners’ accomplishments. After Jane Austen left her childhood rectory in Hampshire, she did not write again until she secured a permanent address in Chawton House. Weary of her nomadic existence, when her brother offered her the use of one of his residences, a delighted Jane wrote, “Our Chawton home when complete, will all other houses beat.” Leonard Woolf philosophized, “What cuts the deepest channels in our lives are the different houses in which we live.” His wife Virginia concurred, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”