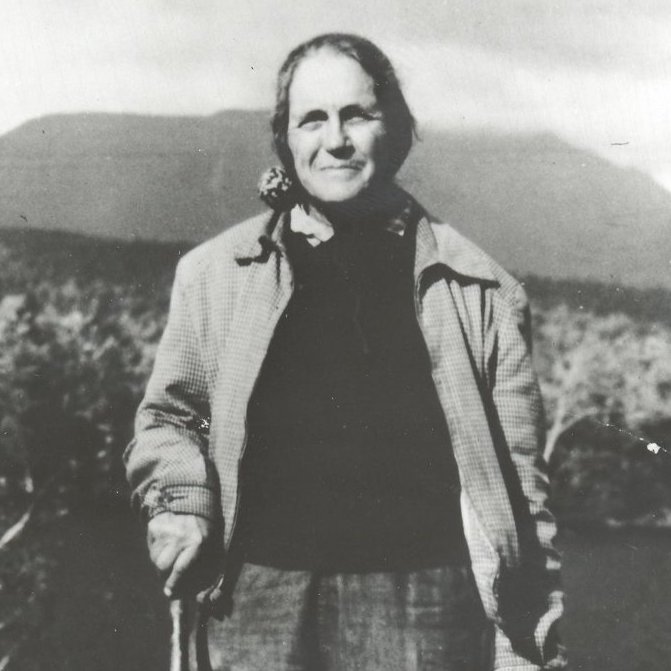

Pick Up Your Feet (1955)

Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th century The Canterbury Tales revolves around a motley crew of pilgrims who share salacious stories to pass the time on their pilgrimage. One of their number, the Wife of Bath, had outlived five husbands though she had managed to elude motherhood. Emma “Grandma” Gatewood served as her diametric opposite: the only commonality is that she was also a pilgrim on a journey that made her the first woman to conquer-unaccompanied- the Appalachian Trail.

The idiom “a walk in the park-” denoting something easy-was never the case for Emma on either a figurative or literal level. She took to the trail to escape the shadow of her past. Her life up to her historic journey had been so rife with hardship she knew she could take anything Mother Nature could dish out.

The Caldwell family was from the socio-economic level that some refer to as “the wrong side of the tracks” while others refer to as “white trash.” Emma Rowena was born in 1887 on a farm in Gallia County, Ohio, near the Ohio River, one of fifteen children-ten girls and five boys-who slept four to a bed. In the winter, the snow on the clapboard roof blew inside the house, and the children would shake their covers before the snow would melt. Her father, Hugh, had lost a leg, along with his moral compass, in the Civil War and consecrated his life to whiskey and gambling. Her mother, Evelyn, raised her large brood in their log cabin. She sent her children to a one-room schoolhouse when they did not have chores at the farm, a rare occurrence. Emma’s formal education ended in the eighth grade-the highest level offered; as she loved learning, she repeated it as often as possible.

Hugh fell at work and broke his remaining leg that necessitated hospitalization for two months. While her mother remained at his side, the seventeen-year-old Emma kept the home fires burning. Upon their return, Emma worked in Virginia as a maid, and when it proved intolerable, she took another job that paid seventy-five cents a week. At that time, she met Perry Clayton (P. C.) Gatewood, considered the great bachelor catch of Gallia County as he had a college degree, who she wed in 1907, at age nineteen. He was eight years her senior, a teacher, and Emma hoped marriage would provide an exit from her hard-knock life. She raised eleven children, built fences, burned tobacco beds and mixed cement, in addition to her household chores. Her haven was the woods where she learned about wildlife, the medicinal properties of plants, which were edible.

Emma’s life transformed to Robert Frost’s “The Road Less Traveled” because of a 1949 National Geographic magazine she had been flipping through while waiting for her doctor’s appointment. She was captivated when she saw photographs of the Appalachian Trail, one she viewed as a window to a wonderful new world. She devoured the article that stated, “The Appalachian Trail (A.T.) is a public pathway that rates as one of the seven wonders of the outdoorsman’s world.” At the time, just one man, a twenty-nine-year-old soldier, Earl V. Shaffer, had hiked the trail in its entirety. After him, five others had done likewise; all had been men. She determined, “If those men can do it, I can do it.” One response to the future question of “Why?” was “I thought it would be a lark;” it was not.

Emma’s first attempt in 1954 ended badly. Starting out in Maine, she broke her glasses, got lost, and rangers came to her rescue. Their stern advice, “Grandma, go home.” Undaunted, the next year she told her children she was going for a walk- which was not a lie. She just omitted the walk would entail hiking 2,051 miles of mountain footpaths, would begin in Georgia and end in Maine. Her omission was based on the certainty her kids would attempt to dissuade their sixty-seven-year-old mother.

Not many women would leave for a lengthy trip with just one change of clothing, but Gatewood was not like many women. Her main outfit was worn jeans, Keds canvas shoes, with a hand-sewn sack slung over her shoulder. Her supplies consisted of a shower curtain as protection against the elements, a Swiss Army knife, a flashlight, an umbrella-which she used to ward off a black bear, a pen, and a small notebook. Dark memories were the only heavy baggage. In terms of food, she brought along Vienna sausages, raisins, peanuts, and bouillon cubes. She felt no need to lug along a tent; like Blanche du Bois, she would depend on the kindness of strangers; in her case, for lodging. On the occasions that did not pan out, Emma slept under a bed of leaves, under picnic tables and once on a porch swing. Gatewood was resolve and determination bundled into a 5’2” body. She wrote in her notebook, “I did not worry if it was to be the end of me. It was as good a place as any.” She determined when she arrived atop Mount Katahdin, her final destination, she would sing “America the Beautiful.”

On her pilgrimage, Emma experienced the best and the worst of nature and humanity-as well as danger. On numerous occasions, she encountered back to back hurricanes on the east coast, a rattle-snake, and bears. Despite the hardship on the trail, she found peace and wrote in her notebook, “the petty entanglements of life are brushed aside like cobwebs.” Word of the elderly woman walking the Appalachian Trail on her own spread like the proverbial wildfire and news of Grandma Gatewood, how the press dubbed “the widow,” proved catnip to reporters from magazines such as Sports Illustrated. In response to why, she provided varying answers, “Just for the heck of it,” “The forest is a quiet place and nature is beautiful. I don’t want to sit and rock. I want to do something,” “I want to see what’s on the other side of the hill, then what’s beyond that.” One article made its way to her hometown, which is how her children learned what she meant when she said she was going for a walk.

Emma completed her journey in 146 days, an average of fourteen miles a day. She would start out at sunrise and not stop until exhaustion took over. As she stood at her final destination, the peak of Mount Katahdin in Maine, she sang. She said, “I told myself I could do it. And I did it.” Throughout her adventure, the public watched her traipse across the evening news on television, wondering whether the older woman, on her own, under inhospitable terrain, would survive. Little did they know what Emma had already endured.

What people knew about Mrs. Gatewood was remarkable: she was the first woman to hike the entire Appalachian Trail by herself in one season. However, as with an iceberg, for the one quarter visible are three quarters that are invisible. The real reason as to why would remain a secret for over half a century.

Gatewood was Ben Montgomery’s great-aunt, and his variation of a bedtime story was listening to tales about the family’s adventurous granny. As a journalist for The Tampa Bay Times in Florida, he decided to investigate the reason, at an advanced age, his relative walked 2,000 miles through fourteen states, risking exposure to rattlesnakes, bears, flooded creeks-she could not swim- and slippery mountain slopes. In a quest to uncover the truth, he contacted Emma’s surviving children who gave him access to her notebook, journals, and letters. In those sources, he discovered what Emma had withheld from news interviews: P.C. had almost pummeled her to death on several occasions. During one beating, he broke a broom over her head. Her children revealed that their father’s sexual appetite had been insatiable, and he forced himself on their mother several times a day. When Emma complained of his sadism, he claimed she was crazy and asked her what asylum she wanted to be committed. In 1937, she fled to relatives in California, leaving behind two daughters, ages nine and eleven. In a letter to her girls-with no return address-she wrote, “I have suffered enough at his hands to last me for the next hundred years.” However, missing her children she returned home. P.C. had mismanaged their farm and, not having enough for the mortgage, they were forced to move to a cabin in West Virginia. A few months later; P.C. beat her “beyond recognition” several times. In 1939, P.C. broke her teeth, cracked one of her ribs and bloodied her face. Their fifteen-year-old son, Nelson, restrained his father which provided Emma the opportunity to escape. Infuriated, P.C. left the house and returned in the company of a deputy sheriff. When her husband flung open the front door, his wife was lying in wait with a five-pound sack of flour which she hurtled in his face. The sheriff arrested Emma; she spent a night in jail until the mayor of the small West Virginia town noticed her blackened eyes and bloodied face and arranged for her release. Her son called her to say his dad was gone, and when Emma returned, she saw P.C. had emptied her home of all the furniture. Freedom arrived after thirty-five years when Emma obtained a 1941 divorce, a great stigma in that era-and raised her youngest children without alimony. To avoid the scarlet letter-D- Emma claimed she was a widow. In her notebook, Emma wrote that she had been “happy ever since.” In 1968, P.C. told Nelson his dying request was he wanted to see Emma walk through his door once more. It was one walk “his widow” refused to take.

Emma’s walking did not end with her first hike. Gatewood returned to thru-hike (hiking straight through in less than twelve months) in 1957, making her the first person, male or female, to twice tackle the Appalachian Trail. Gatewood said the second time was so she could enjoy it. She completed the trail again in 1964, at age seventy-five, in sections, becoming the first person to hike it three times. In addition to tenacity, Emma had a sense of humor. When Groucho Marx interviewed her on his television show, You Bet Your Life, he asked, “What did your folks raise on your farm in addition to you?” Emma replied, “Tobacco, corn, wheat, and a little Cain.”

In 1959, she headed west, walking from Independence, Montana, to Portland, Oregon, as part of the Oregon Centennial celebration. She left two weeks after a train wagon but passed it in Idaho. The trip covered nearly 2,000 miles and took ninety-five days. The odyssey of Grandma Gatewood resonated with women who felt someone nearing seventy could hike it in one season, many felt they could follow in her footsteps. The publicity the hiking grandmother garnered brought the Appalachian Trail into the spotlight. Sections of the trail had been poorly maintained, but after her odyssey, conservation efforts concentrated on its upkeep. Grandma Gatewood Memorial Trail, a six-mile hike located in Hocking Hills State Park in Ohio, serves as a tribute to her legacy. Every January, thousands gather in her honor and take part in her favorite pastime-walking. When a fellow hiker had asked her which part of the trail she liked best, she responded, “Going downhill, Sonny.”

In 1973, Emma awakened from a coma, hummed a few bars of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and closed her eyes. On her epic trek, Emma followed the advice her father had given her as a child, “Pick up your feet.”