Mary Lincoln House

Eternal

“I am bound to the earth with sorrow.” Mary Todd Lincoln after the assassination

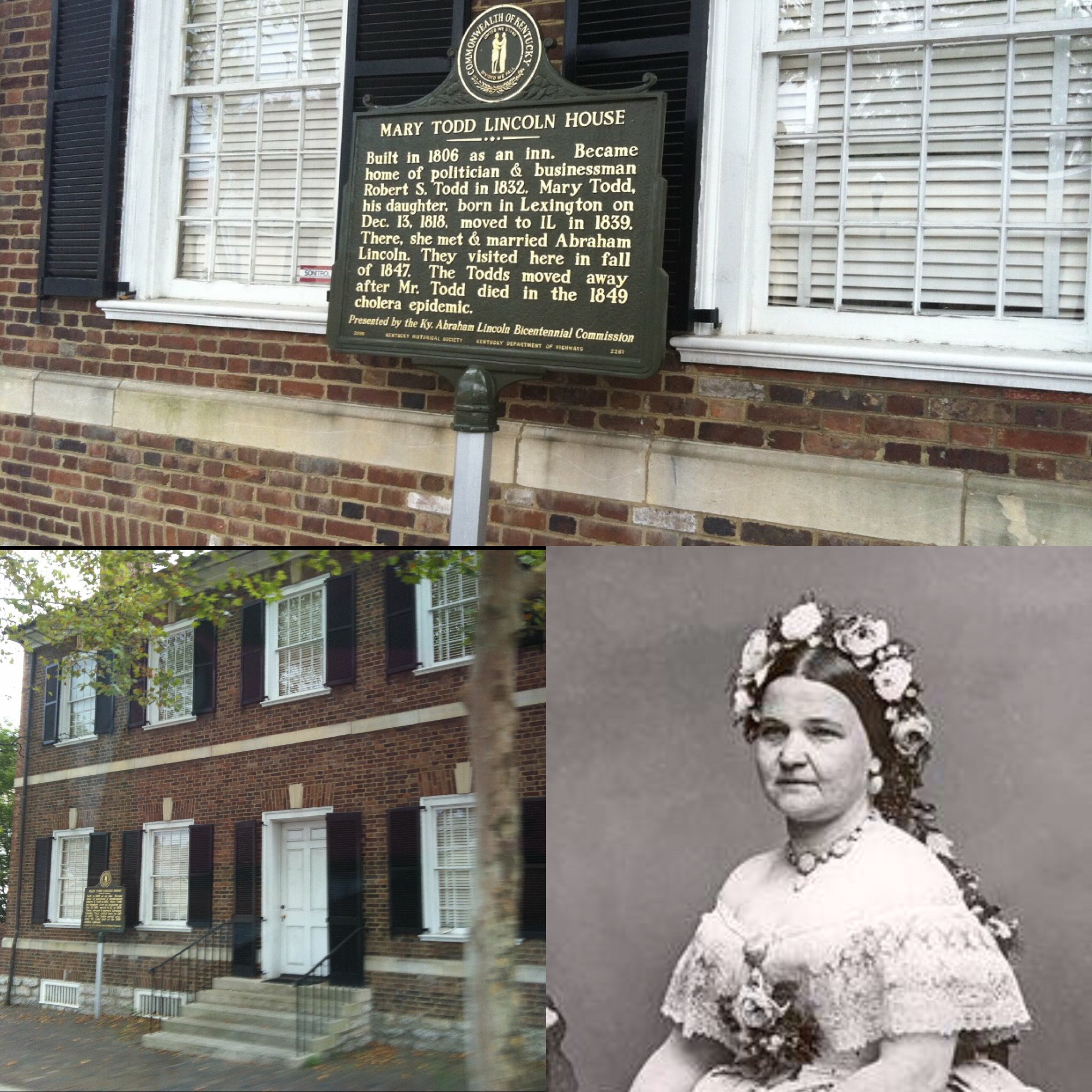

Mary Todd Lincoln House (opened 1977)

Lexington, Kentucky

Stephen Foster’s signature song, “My Old Kentucky Home,” expresses a slave’s longing to be reunited with his family in his far away blue grass state. Trapped in the eye of the Civil War storm, Mary Todd Lincoln also pined for her old Kentucky home. To walk the same halls as Mary and President Lincoln, one can tour the Mary Todd Lincoln House.

British school children learn a rhyme to remember the wives of King Henry VIII, “Divorced, beheaded, died; Divorced, beheaded, survived.” While the First Ladies never dealt with beheading, (at least not literally,) their lives were as dramatic as the consorts of the right royal rotter. The sixteenth FLOTUS’ life proves inhabiting the East Wing is not for the faint-hearted.

Mary Ann was born in 1818, one of seven children, in Lexington, known as “the Athens of the West,” to parents Robert and Eliza Todd, the city’s aristocrats. In theory, Robert was against possessing human chattel; however, he owned five slaves. One of them, Mammy Sally, confided to Mary that their gate bore a mark signifying it was a place runaways could seek help.

After bearing six children, Eliza passed away, a traumatic event for the six-year-old Mary. A few months later, Robert married Elizabeth Humphrey, with whom he had nine children. Mary recalled her childhood as desolate due to her stepmother and in retaliation, Mary played pranks on her such as putting salt in her coffee. Stepmother Dearest pronounced Mary “a limb of Satan.” Her father was unable to attend to his fifteen children as he was often away serving in the state capital’s the House of Delegates.

At the time that the Todds moved into their elegant twenty-room house, Mary enrolled in a school run by Charlotte Mentelles who had fled during the French Revolution. A standout student, Mary understood she was highly intelligent but was also aware the brass ring was hooking a husband. Nevertheless, she determined to marry for love, “My hand will never be given, where my heart is not.”

At age twenty, Mary moved in with her married sister, Elizabeth Todd Edwards, in Springfield, Illinois. Her brother-in-law, Ninian, remarked of the teenaged beauty, “Mary could make a bishop forget his prayers.” In the Edwards’ home Mary met Abraham Lincoln who later referred to himself as “a poor nobody then.” He was a rough around the edges lawyer, born in a Kentucky log cabin. At a cotillion, Lincoln had told Mary, “I want to dance with you in the worst way.” Physically, they were opposites: he was six feet four, rail thin, with dark hair; Mary was five feet two, plump, with blue eyes. They bonded over mutual interest in politics and abhorrence of slavery. After a brief estrangement, during which period Abraham described himself as “the most miserable man living,” the thirty-four-year-old walked down the aisle with his twenty-four-year-old bride. The Todds were against their match as Lincoln was not of their social strata. A week after the wedding, Lincoln declared his marriage was “a matter of profound wonder.” Mary told a friend, “He is to be President of the United States some day. If I had not thought so I would never have married him, for you can see he is not pretty.” As an observer noted, Lincoln was “a gloomy man-a sad man. His wife made him President.” After his 1860 presidential victory, Lincoln strode along the street of Springfield shouting, “Mary, Mary, we are elected!”

While her husband’s legacy is as the country’s greatest president, Mary was a magnet for malevolence. In a move that future First Ladies should have heeded, (Nancy Reagan,) Mary went over budget redecorating the White House. The public viewed her as an American Nero who fiddled with wallpaper while the Republic burned. When Lincoln learned of the sky-rocketing expenditure, it marked one of the few times his aides heard him berate her for splurging on “flub dubs” while his soldiers did without. Detractors pilloried Mary for her lavish clothing expenditures, (Nancy Reagan.) The First Lady loved the attire of Empress Eugénie, but it did not love the middle-aged Mary back. She favored low-cut gowns that displayed what a senator called her “milking apparatus.” Her husband critiqued her dresses that consisted of long trains and exposed shoulders and remarked she needed “a little less tail and little more neck.” Unlike Lincoln who was “almost a monomaniac on the subject of honesty,” she falsified bills, misappropriated funds. After accepting lavish gifts, she badgered her husband to award plum appointments. Her staff were disconcerted with her drastic mood swings, and explosive temper; most likely, she was a victim of bipolar. In the grip of rage, she threw hot beverages at her spouse, and delivered a blow to his face that drew blood. William Herndon, who had been Lincoln’s law partner, denounced her as a “she-wolf.” John Hay, Lincoln’s social secretary during the Civil War, referred to her as “the Hellcat.” Mary served as the whipping girl of the White House as Northerners distrusted her as six of her stepbrothers were fighting for the Confederacy; Southerners hated her as her husband was hell-bent on making the South a civilization gone with the wind.

In 1862, Mary grieved the death of her eleven-year-old son, Willie-probably from typhus- who had been preceded in death by his three-year-old brother, Eddie. As would be the case with First Lady Nancy Regan who relied on her astrologer, Mary arranged White House seances to communicate with her beloved boy. Yet there was something about Mary that made her husband remain devoted, “My wife is as handsome as when she was a girl, and I…fell in love with her; and what is more, I have never fallen out.” And there was much to admire as she visited wounded soldiers, aided escaped slaves, was the first FLOTUS to open the White House to black guests. After asking for a pardon for a deserter, Lincoln complied “by request of the Lady President.”

On April 14, 1865, the Lincolns, along with their guests, Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris, were at the Ford Theater watching a performance of Our American Cousin. Concerned about the appropriateness of holding her husband’s hand, Mary inquired, “What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you so?” His response were to be his last words, “She won’t think anything about it.” A few moments later, John Wilkes Booth fired his derringer. A hysterical Mary cried out, “Why didn’t they shoot me!”

The widow, who wore black for the remainder of her days, remained in bed in the White House for forty days. Mary never recovered from the shock and in 1871 received another one at the loss of her third son, the eighteen-year-old Tad. Her behavior became erratic and Robert, her only remaining child, committed her to Bellevue Place, a woman’s insane asylum, where she remained for three months. Heart-broken, Mary lamented, “I wish I could forget myself.”

To prepare for her role as the First Lady in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, Sally Field visited the Mary Todd Lincoln house-the first historic site dedicated to a First Lady. At the end of the film, Mary told her husband that if people want to understand him, they would have to understand her. Stepping over the threshold, the pages of the calendar turn in reverse. In the drawing-room, Nelson, the butler, pours his famed mint juleps to the crème of Kentucky society: Henry Clay, three times a presidential candidate, John Breckinridge, a future vice-president, Cassius Clay, founder of the Republican party. The halls rustle with the swish of silk and crinoline. The 1803 brick estate was originally an inn; when Robert purchased the property, he separated the ballroom into twin parlors. The most famous guest, Abraham Lincoln, stayed for three weeks in 1847 where he indulged in the extensive library. Guests thrill to touch the cherry wood banister on which the Great Emancipator had once placed his hands. In the front parlor is a painting of the forty-five-year-old Mary, hair adorned with flowers. The desk in Mary’s bedroom holds a miniature painting of Charlotte Mentelle; Meissen porcelain perfume jars remain on display. The master bedroom, where Robert conceived many of his fifteen children, holds a Currier & Ives print of President Washington. The children’s room has a glassed-in case with a silver cup a friend gifted Todd in sympathy for the loss of Wille.

Amid the treasures, in a guest bedroom, is the original playbill of Our American Cousin. The talisman transports viewers to a fateful nineteenth century Good Friday evening that destroyed those in the Presidential box. Clara married Henry and the couple had three children. In 1883, in the grip of madness, he murdered his wife and repeatedly stabbed himself. He survived and ended his days in an insane asylum. The slain president’s remains underwent seventeen exhumations until he had his final resting place- under ten feet of cement.

A recluse in Elizabeth’s home, nearing her end, Mary requested that she should lie “beside my dear husband & Taddies’ on one side of me.” Mary passed away in 1882; her coffin situated in the same spot where, forty years earlier, she had stood as a bride. On Mary’s finger was the wedding ring that Lincoln had inscribed, “Love is Eternal.”

A View From Her Window:

In the back of the Todd house was a magnificent garden. Gazing upon the beauty of the flowers, a young Mary never could have fathomed what an incredible tapestry the Moirai, the personifications of Fate, would weave.