Do Not Pass Go (1904)

Nostalgia comes to call with the opening of a box filled with silver trinkets, brightly colored cards, plastic pieces of real estate. It offers a flight of fancy where, for a time, one could be lord of many manors. If unlucky, we would end up behind bars; if savvy, we would become as wealthy as Rich Uncle Pennybags.

The board games of our yesteryears act as Proustian madeleines, a pastime that perhaps shaped our world views. The most prevalent of these was Monopoly that taught ‘to the victor belongs the spoils.’ Played by everyone from Jerry Hall and Mick Jagger to Carmela and Tony Soprano, it scratches an itch to wheel and deal few of us can reach in real life. The game is sufficiently redolent of unbridled capitalism that in 1959 Fidel Castro ordered the destruction of every Monopoly set in Cuba, while these days Vladimir Putin seems to be the ultimate aficionado. The cardboard board is as famous as the curvaceous Barbie, but its true origin has purposely been delegated to the shadows.

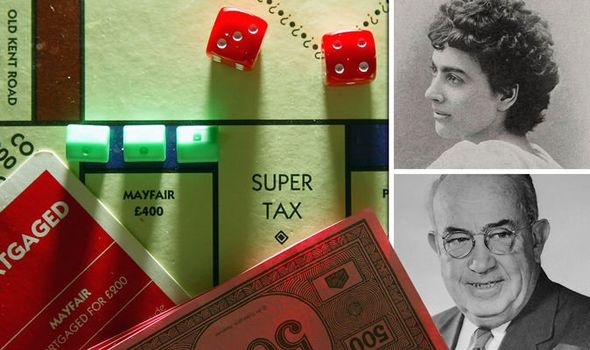

For generations, the story of Monopoly’s Depression-era birth delighted fans almost as much as the board game itself. The tale, tucked into the game’s box along with the Community Chest and Chance Cards, was that Charles Darrow had a eureka moment. After selling the game to Parker Brothers, he lived lavishly ever after. The trouble was the story is as mythical as George Washington and the cherry tree.

In the case of Monopoly, the term ‘mother of invention’ is not just an accidental nod to the feminine as its genesis can be traced to a woman who took the road less travelled. Elizabeth, (nicknamed Lizzie), Magie, a Quaker, descendant of Scottish immigrants, was born in Macomb, Illinois; father, James, was a newspaper publisher and abolitionist who accompanied President Lincoln as he travelled around Illinois debating politics with Stephen Douglas. Elizabeth stated, “I have often been called a ‘chip off the old block,’ which I consider quite a compliment, for I am proud of my father for being the kind of an ‘old block’ that he is.” James ran for public office on an anti-monopoly ticket-an election he lost, but his message was not lost on his daughter.

Elizabeth supported herself as a stenographer, barely able to scrape by on her $10.00 a week salary. To draw attention to the plight of unmarried women, exploited in the workplace, she staged an audacious stunt, one that made national headlines. Purchasing an advertisement, she offered herself for sale as a “young woman American slave’ to the highest bidder. She explained to reporters, “We are not machines. Girls have minds, desires, hopes and ambition.” Due to her notoriety, in 1906 she obtained a job as a journalist. Despite the difficulty of supporting oneself without a husband, Magie was reluctant to walk down the aisle. She described marriage as “a germ” and likened it to “a disease.” Her philosophy was not just related to the economic ills of capitalist society: “What is love? Nobody knows.” She said matrimony was not for her unless she could see her spouse only once every three days. She did not want anyone to interfere with her ability to retreat into her den and spend hours with her books. She commented, “Personally, I love solitude, and were I married I could not enjoy this luxury.” Apparently, she met the man who fit this bill; four years later she married Virginian businessman, Albert Phillips, who, at age 54, was ten years her senior. The marriage raised eyebrows-a woman who had remained single well beyond the sell-by-expiry date and a man becoming the husband of a wife who had publicly expressed skepticism of the institution of marriage. In her spare time Elizabeth wrote poetry, short stories, and performed on stage, where she earned praise for her comedic roles. She also spent her time drawing up a game based on George’s anti-monopoly beliefs. She felt this venue was an excellent way to convince people of the evils of corporate greed.

Magie’s brainchild-the Landlord’s Game- featured a path that allowed players to circle the board in contrast to the linear path popular at the time. It included money, railroads, properties, and the three words that have endured for more than a century after Elizabeth scrawled them: “Go to Jail.” Its Chance cards had quotations such as John Ruskin’s, “It begins to be asked on many sides how the possessors of land became possessed of it,” and Andrew Carnegie’s, “The greatest astonishment of my life was the discovery that the man who does the work is not the man who gets rich.” She created two sets of rules: an anti-monopolist set in which all were rewarded when wealth was created, and a monopolist set in which the goal was to build a fortune by destroying the nest eggs of your opponents. Her dualistic approach was meant as a teaching tool to demonstrate that the first set of rules was morally superior. Magie’s intent was her brainchild would serve as a rebuke to the land barons of the Gilded Age. The game made its way to Atlantic City Quakers where they altered the property names from Elizabeth’s Manhattan ones to those from their neck of the woods.

The man who received credit for creating Monopoly was a Pennsylvanian, Charles Darrow, not an inventor, but an opportunist. He was unemployed, with an invalid child, struggling for survival during the Depression. Charles and his wife Esther were introduced to Magie’s game by another couple, and a light bulb went off how he could market it as his own. He asked his friend, Franklin Alexander, a cartoonist who had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, to create illustrations such as Mr. Monopoly-based on J. P. Morgan- and the whistle-blowing cop. Darrow sold the reinvented product to Parker Brothers for $7,000 plus residuals. By 1936 the board game garnered millions, saving not only Darrow but also the game company, from financial ruin. Fortunately for the Darrow descendants, they kept the original game in their possession until 1992 when Malcolm Forbes purchased it for a princely sum. Parker Brothers gave the mother of the invention a onetime pay-off of five hundred dollars.

At first, the then -elderly Elizabeth was pleased with the purchase. She hoped the company would turn her “beautiful brainchild” into a popular way of disparaging greedy monopolists. She was infuriated when she discovered they had a different game plan. To add insult to injury, Darrow and the proprietors made sure Magie’s name had as little connection as possible to the lucrative blockbuster. When journalists questioned how he had come up with the phenomenally successful game, his stock response, “It’s a freak. Entirely unexpected and illogical.” Darrow had monopolized Monopoly. In 1936, amid the media frenzy surrounding ‘the inventor’ and the nationwide Monopoly craze, Magie lashed out. She gave an interview to the Washington Post where she expressed anger at the appropriation. Gray hair tied back in a tightly coiffed bun, she held up the board from the Landlord’s Game and Parker Brothers’ Monopoly to illustrate their shared DNA. She stated that although the company had the rights to her three-decade-old patent that had passed into public domain, they did not give credit where credit was due. They had kidnapped her child and passed it off as their own. They never righted the wrong. One of Elizabeth’s last jobs was at the US Office of Education; here her colleagues knew her as an elderly typist who claimed ownership of Monopoly. She died in 1948, a widow with no children-and an aborted legacy. Her obituary made no mention she was the mother of Monopoly. In contrast, the Charles Darrow myth persisted as an inspirational parable of rags to riches ingenuity; his niche secured as the Depression era Horatio Alger. Darrow became an industry legend for inventing a story rather than for inventing an economic eureka.

Elizabeth Magie would be pleased with her posthumous recognition. However, she would be gobsmacked at the changes time had wrought. There is now an app for Monopoly, as well as an electronic banking edition introduced in 2006 that features debit cards instead of cash, and tokens include a Segway and a flat-screen TV. She would be equally astounded it even played a role in history. In World War II, Monopoly boards, by that point a symbol of capitalism and America, were used to conceal maps sent by the Allies to prisoners of war.

During her lifetime the game had proliferated, selling just over two million in its first years of production. Currently, at least one billion people in 111 countries have played Monopoly, with an estimated six billion little green houses manufactured. The iconic board has undergone many face-lifts: it has adopted the streets of almost every major American city, and various versions have appeared such as Berkshire Hathaway, Chicago Bears, the Simpsons, Corvette, and John Deere. There have been odd sets as well: the Disney Villains, the Walking Dead, and Sun- Maid. One incantation that would send the Quaker founder reeling would be the bling version created by San Francisco jeweler Sidney Mobell, made of 18 karat gold and diamonds, valued at 2 million. Even more disturbing would be Ghettopoly whose main ‘playa’ is far from the top hat wearing mascot. Instead there is a bandanna-wearing African American male holding an Uzi and a bottle of liquor. A sample token is a marijuana leaf, while a typical chance card reads, “You got da whole hood addicted to crack, collect $50.00.”

Monopoly continues to wield its hold; after all, who can resist the endorphin rush of bankrupting friends and family? And for all the capitalists in training, the seed is planted that if they can put into practice the principle of the game they too can become the contemporary rich Uncle Moneybags, a megalomaniac billionaire who married an Eastern European model and lives in baronial splendor. Its premise can be summed up by Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko, “The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good.”

As for Charles Darrow, who misappropriated a Quaker woman’s brainchild, the final epitaph could be: Do Not Pass Go-Do Not Collect $200.00.