A Tarnished Reputation (1943)

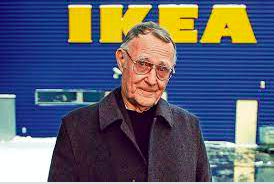

What’s blue and gold, serves meatballs, and is the size of five football fields? If you guessed IKEA you are correct, though you might not be able to decern the acronym behind the Swedish juggernaut’s name. The founder of the emporium christened it after his initials and his childhood home: I for Ingvar, K for Kamprad, E for Elmtaryd, his family’s farm, A for Agunnaryd, his village. Behind the do-it-yourself furniture is the tale of the man who could well have merited inclusion in a Reader’s Digest column, “The Most Unforgettable Character.”

Mozart was a prodigy in music, Picasso in art, Fischer in chess, Ingvar in business. He was born 1926 to mother, Berta, and father, Feodor Kamprad, a German immigrant. He grew up in the poor province of Smaland, in southern Sweden, a dyslexic boy who struggled in school. At age five, he sold matches and lingonberries to his neighbors and by age eleven had earned enough to buy a bicycle. Five years later, Ingvar founded a mail-order company, IKEA, delivering products with the local milk wagon. As many local farmers made furniture as a sideline, Ingvar added these to his stock. His breakthrough moment occurred, when, unable to put a table in a car trunk, he launched the “flat pack” concept of home-assembly furniture that saved on consumer cost. Kamprad opened his first brick and mortar store in 1958 that offered customers coffee and cake in its café and schnapps at the checkout. By 1951, he had earned his first million kroner. The following year he married Kerstin Wadling, with whom he adopted a daughter, Annika. The marriage ended in an acrimonious divorce; Kamprad admitted “he had been a real shit.” His second wife was Margareth Sennert, with whom he had sons Peter, Jonas, and Mathias.

The bright blue-and yellow stores-the colors of the Swedish flag-spread across the world as did its catalogues. With approximately 200 million annual copies its circulation surpasses that of the Bible, the Koran, and Harry Potter. A statistic claims that ten percent of Europeans can trace their conception to an IKEA bed. The Swede’s business acumen garnered Ingvar a net worth of $58 billion.

Despite his fortune, Kamprad took great pride in his reputation as a Swedish Scroodge. He drove an old Volvo, pilfered salt and pepper packets from restaurants, and dressed in clothes from thrift shops. In 2008, Sweden erected a statue of its famous son, and Ingvar oversaw the ribbon-cutting ceremony. Ever thrifty, he elected to merely untie the ribbon and handed it to the mayor for him to use on another occasion.

However, there was another side behind the public image: Kamprad was an alcoholic, owned a Porsche and a Swiss home overlooking Lake Geneva. Even more daunting, he had ties with Nazi skeletons in his closet. During World War II he had been a member of the Swiss fascist organization, and even after it ended had remained friends with the right-wing founder, Per Engdahl, who he invited to his wedding. Jewish groups asked for an official boycott and Ingvard’s response was he would erect an IKEA in Israel. He admitted he had been a real shit and that his fascist activities were “a part of my life which I bitterly regret” and “the most stupid mistake of my life.” In his autobiography he asked, “When is an old man forgiven for the sins of his youth?”

Kamprad passed away in his sleep at age ninety-one. Ever the planner, he specified his final resting place would be in a birch grove in Sweden. His tragedy was that his empire’s meatballs did not come with a sauce that would whitewash a tarnished reputation.