Yes-No

Joke at the time of the murders: Someone asked Miss Lizzie the time of the day.

“I don’t know, but I’ll ax father.”

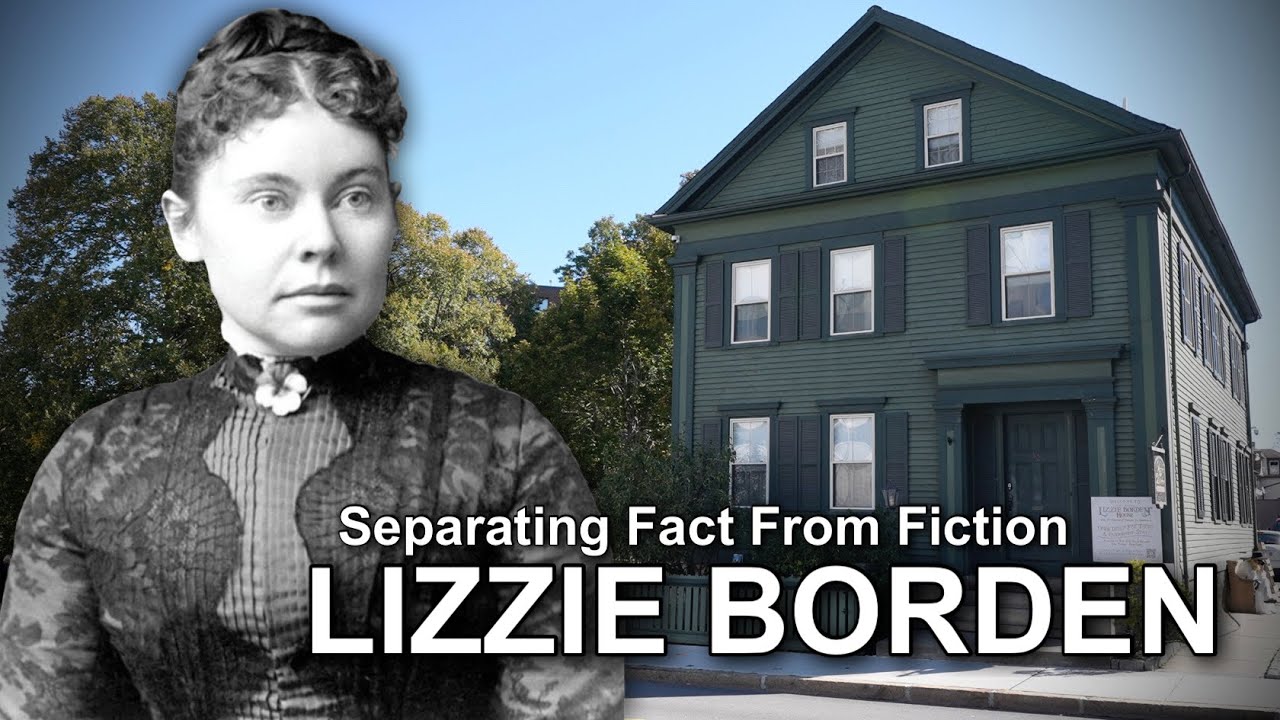

The Lizzie Borden House (opened in 1996)

157 Third Street, Fall River, Massachusetts

A popular seventeenth century nursery rhyme is, “Three blind mice. Three blind mice. See how they run. See how they run. She cut off their tales with a carving knife…” The dark story behind the light-hearted ditty: the three blind mice were Protestant loyalists, burned at the stake by Queen Mary. A nineteenth century American counterpart is similarly macabre, “Lizzie Borden took an axe/ And gave her mother forty whacks/ When she saw what she had done/ She gave her father forty-one.” If the latter rhyme holds true, Lizzie embodied Shakespeare’s description of King Lear’s daughters, “Sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child.”

Television viewers are smitten with The Forensic Files because of a thirst for tales involving murder. And a headline that has whetted the public interest for 125 years involved a most unlikely suspect. Andrew Jackson Borden, who started his career as an undertaker and ended it as the president of the Union Savings Bank, was a Fall River, Massachusetts, Scrooge. His wealth-$8.3 million in contemporary currency- could have bought a home on The Hill, the town’s wealthy enclave, but he was too tight-fisted to leave the less expensive downtown sector. His backyard was far from a stately English garden: the Bordens used theirs to empty their slop pails, an easier approach than using the home’s basement toilet. The backyard also doubled as a vomitorium when the need to upchuck arose.

After the passing of his wife Sarah, needing a mother for his young children, Emma and Lizzie, Andrew married Abby Durfee Gray. The union proved joyless; Andrew never wore his wedding band. Never warming up to the woman she considered an interloper, Lizzie hostilely referred to her as Mrs. Borden. The sisters were cut from very different clothes. Emma, the elder sibling, was shy and unassuming. Her only existing photograph shows her covering her face with her left hand. The outgoing Lizzie worked as a Sunday school teacher and served as a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Their commonality: ill will towards Abby.

Lizzie’s link to infamy began on a stifling hot 1892 morning when the Bordens’ maid, Bridget Sullivan, (whom the family called Maggie), took ill and vomited in the backyard. Indeed, everyone in the household had been retching for days. Alarmed, Abby contacted Dr. Seabury W. Bowen with her fears regarding poisoning. The physician responded that the culprit was most likely warmed-over mutton-Andrew did not like to throw out food. Furious his wife was wasting money, Andrew refused to let the doctor examine his family.

On that fateful day, Lizzie ran into the street and called out to her neighbor, “Oh, Mrs. Churchill, do come over. Someone has killed father!” With those chilling words, Lizzie entered history as a victim, a villain, a jumping-rope chant, and a media sensation of the Gilded Age. When the hapless Adelaide Churchill entered the Borden house, she spied Andrew lying on the parlor couch, hacked to death to a point where his face was unrecognizable. One of his eyeballs was cut in half. He was dressed in black; on his pinkie finger, he wore a ring-a gift from Lizzie. His assailant had whacked him ten times with a hatchet-like weapon. Abby was on the floor of the guest bedroom, her body partially obscured by the bed. Her murderer had struck her nineteen times.

By the next morning, 1,500 gawkers had gathered outside the scene of the double homicide. Rumor was rife that Jack the Ripper had come to America to claim his next targets. However, the only serious suspect was Lizzie. Damning evidence was she had reportedly tried to buy highly poisonous prussic acid the day before the murders. The pharmacist refused her request despite her assurance she wanted the chemical to clean a seal-skin coat. There was also a widespread belief that she had burned her dress in the kitchen stove. Fall River residents took her alleged act as a nail in the coffin of culpability as the thrifty Borden women would have used a worn-out frock for a patchwork quilt or for rags.

The police arrested Lizzie who spent ten months in jail awaiting trial in New Bedford. Publicity surrounding the news surpassed coverage of the Chicago World’s Fair. The all-male jury acquitted her on the mindset that the white, Christian, New England, daughter of a banker could not have perpetuated such a heinous act. In addition, they did not want to hang a woman. Perhaps the verdict was a foregone conclusion as the judge’s charge to the jury was a thinly veiled instruction to vote for her innocence.

Although the men of jury gave Lizzie a pass, the finger of guilt can be pointed in her direction as she was the possessor of motive. She hated her stepmother and was concerned that her father had deeded some property to his in-laws. Moreover, with the removal of Andrew and Abby, she would no longer be under their financial thumb and could escape from an unhappy house.

The lawyer for the defense, Andrew J. Jennings, deposited everything related to the trial in storage, and never spoke of the case again. Seventy years later, his daughter donated the evidence to the town’s historical society. The stash included Abby’s dust cap, blood-stained pillow shams from the guest room, locks of the victims’ hair, two paper tags labelled the Bordens’ stomachs, and a hatchet missing a handle. Visitors to the Center always make a beeline to gristly souvenirs, and there is a brisk trade selling tote bags and calendars emblazoned with Fall River’s most infamous woman.

With their hefty inheritance, the sisters purchased Maplecroft, a four-bedroom house on The Hill. Free of Andrew’s frugality, Lizzie applied gold-leaf to her bedroom ceiling. To her consternation, although acquitted at her trial, she did not fare as well in the court of public opinion. At church, the townspeople would not sit in the pew beside her, children pelted her windows with rotten eggs, and randomly rang her doorbell. Lizzie again courted controversy when a jewelry store in nearby Providence accused her of shoplifting. Another scandal stemmed from her perceived crush on actress Nance O’Neil, the reason Lizzie threw a party for a theatrical troupe. Emma subsequently moved out; the sisters remained estranged.

Lizzie, who had changed her name to Lizbeth after her move, died in 1927. Her internment was in Oak Grove Cemetery where her grave resides with the rest of the Borden family. The only people present for her burial were the undertakers. Her infamy has never disappeared, and vandals over the years have left graffiti on her tombstone.

The three-story, Victorian Borden home is currently a bed and breakfast/ museum where tourists can spend the night in the room where Abbey met her gruesome end, sit in the parlor couch from which Andrew never rose. The gory scene has led to gallows humor. In Abbey’s execution room hangs a sign: “Caution! Watch your head! Low ceiling. There Have Already Been Two Fateful Head Injuries in This House.” The gift shop offers creepy kitsch hatchets on keychains, earrings, and T-shirts. The most popular-selling item is a blood-splattered Lizzie Borden bobble-head doll. The guests come for the museum’s macabre element, or because they are amateur sleuths, trying to cast light on an unsolved murder. Some try to summon Lizzie with a Ouija board, hoping for a posthumous breakthrough of the unsolved mystery.

The answer to America’s long-stand Who Dunnit It? answer lies in the far-left corners of a Ouija board: YES-No.

A View From Her Window-

Rather than Lizzie’s view, in the words of Keats’, “being a joy forever,” it doubled as a vomitorium. Her dining-room window afforded her a view of Mrs. Churchill’s house, the neighbor who heard the unwelcome news that a double homicide had been committed and she should, “Come quick!”

NEARBY-ATTRACTION: FALL RIVER HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Established in 1921, the French Second Empire mansion was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. The museum’s mission is to preserve the history of Fall River. The interior of the estate showcases the beauty and authenticity of its era, while its lawn displays a beautiful Victorian garden. The museum’s exhibits hold the world’s largest collection of artifacts pertaining the life and trial of Lizzie Borden, the town’s notorious daughter.