Wrong for Women

Wrong for Women

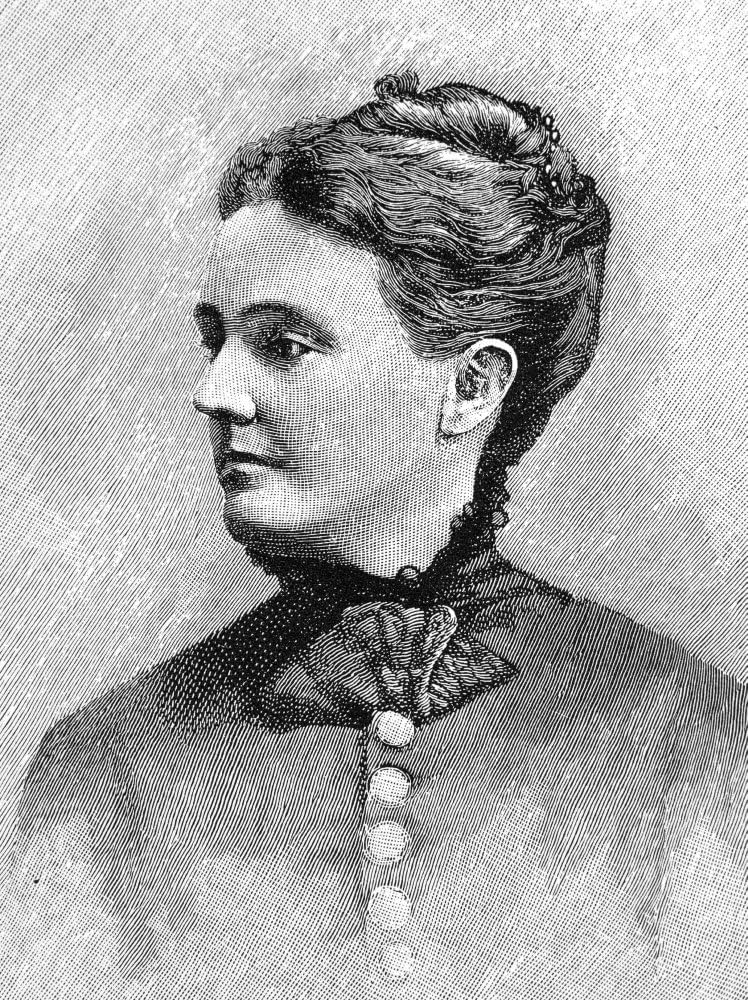

Sarah Orne Jewett

“Love isn’t blind; it’s only love that sees.”—Sarah Orne Jewett

Sarah Orne Jewett House (opened 1931)

Sarah Orne Jewett observed, “We unconsciously catch the tone of every house in which we live.” The quotation rang true for the author, whose ancestral home formed the bedrock of her soul. To catch the author’s tone, travel to the Sarah Orne Jewett House.

Rudyard Kipling said Jewett’s 1896 The Country of the Pointed Firs was the female version of Walden, and “the realist New England book ever given us.” Theodora Sarah Orne Jewett hailed from South Berwick, Maine, situated on the Piscataqua River. In an essay she wrote, “I am proud to have been made of Berwick dust.” The author was born in 1849 in her grandfather’s, Captain Theodore Furber Jewett, grand eighteenth-century home.

After the captain’s son, Theodore, and his daughter-in-law, Caroline, had children, Mary and Sarah, he built them a home of their own next door. In the smaller residence, the Jewetts welcomed their third daughter, Caroline (Carrie). The townspeople referred to the sisters as “the doctor’s girls.”

At an early age, Sarah contracted rheumatoid arthritis, and her father thought it more beneficial for her to accompany him on his rounds than sit in a classroom. Through their horse-and-buggy rides to remote locales, Sarah made the acquaintance of every stratum of South Maine society: judges, shipowners, schoolmasters, and paupers. Cocooned in a magical childhood, Sarah was New England’s Peter Pan, evidenced by a letter she wrote to Sara Norton, “This is my birthday, and I am always nine years old—not like George Sand who began a letter, ‘It is now eight thousand years since I was born.’” Sarah wrote the letter in her forties.

What set Sarah apart from other South Berwick women can be gleaned from her teenage diary. An early infatuation was Cecily Burt who she met at church when visiting Cincinnati. After a prayer meeting, she wrote, “I do love her best of anyone here in the whole city.” Before she headed home, Cecily gifted her a gold ring of which Sarah wrote, “I had rather have it than anything for I shall always have it with me.” The news of Cecily’s engagement delivered a crushing blow. Unable to follow her father into medicine because of her gender, and perhaps spurred by romantic rejection, Sarah turned to another aspiration.

At age nineteen, following several rejections, Sarah embraced her first success when the prestigious Atlantic Monthly published her short story “Mr. Bruce.” Her most notable work was her bildungsroman (a word of German origin that refers to a coming-of-age novel), A Country Doctor. Other notable books that cemented her literary niche were A White Heron and Other Stories and The Country of the Pointed Firs. A common denominator of her work is they depict the color and character of rural Maine. Eventually, she earned enough income to achieve financial independence.

Not only did Sarah contribute to literature, she likely influenced the work of famed novelist Henry James. In 1886 James published his The Bostonians, inspired by the cohabitation of Sarah Orne Jewett and her partner, Annie Fields. Although he did not employ the term “Boston Marriage,” his novel popularized the expression that referred to the turn-of-the-century relationships between two unmarried women who shared a home. These partnerships were accepted in New England, especially in Boston. The unions did not raise eyebrows (as was the situation with their male counterparts), due to the Victorian mindset that women were asexual and therefore nothing untoward took place behind closed doors.

Annie Fields, remembered as the beautiful society hostess of whom Charles Dickens was an admirer, was the wife of James T. Fields, the founder of The Atlantic Monthly. Extremely accomplished, she was an internationally acclaimed hostess of a literary salon she held at her home on 148 Charles Street, Boston. After James’s death, she fell in love with Sarah, also a doctor’s daughter, who shared her passion for writing and travel. Through Annie’s publishing connections and Sarah’s literary ones, their circle included some of the eminent people of the era: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Julia Ward Howe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Makepeace Thackeray, among other literary luminaries. While South Berwick remained Sarah’s base, she spent a great part of each year on Charles Street as well as at Annie’s summer home in Manchester-by-the Sea on the North Shore of Massachusetts. Annie and Sarah’s wealth afforded the opportunity to travel, and the couple visited destinations such as Greece, Italy, England, and France. Their love was manifested in many ways, such as nicknames: Sarah was Pinny; Annie was Fuff. Their cache of love letters whispers their intimacy, “Are you sure you know how much I love you?” “And when I think it was my dear little Fuffy who wrote it . . . ” Half of me . . . stays with you . . .”

The blows that buffeted Sarah’s life were the loss of loved ones. In 1878 Sarah learned of her father’s passing through a telegram and wrote of his death, “I know that the later loneliness is harder to bear than the despair that comes at first.” Thirteen years later, Caroline succumbed to the illness from which she had long suffered. The character of Almira in The Country of the Pointed Firs expressed the author’s sorrow, “You never get over bein’ a child long’s you have a mother to go to.” To convince herself that despite being an orphan, she was still nine years old, she borrowed her nephew’s, Theodore (Stubby) Jewett Eastman, sled and careened down a slope. She was forty-one years old.

As a mentor to Willa Cather, Sarah impacted the Southern writer, as well as American literature. Sarah imbued Willa with the belief she could succeed in her literary aspiration and move in with her lover, Edith Lewis. In tribute, the dedication page to Willa’s 1913 novel, O Pioneers!, states, “To the memory of Sarah Orne Jewett, in whose beautiful and delicate work there is the perfection that endures.” In 1925, in the introduction to an edition of The Country of the Pointed Firs, Willa wrote that literary immortality was guaranteed to only three American novels: The Scarlet Letter, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and The Country of the Pointed Firs.

In the fall of 1902, on Sarah’s fifty-third birthday, she invited her sister Mary and friend Rebecca Young for a drive along the river marshes to enjoy the autumn foliage. As they descended a hill, their horse stumbled causing Sarah and Rebecca’s ejection from the carriage. Sarah suffered a concussion and a fractured vertebra and spent time convalescing on Charles Street. For years she suffered from the debilitating injury. Sarah passed away in the home that had remained a constant in her life.

Sarah Orne Jewett House

Willa Cather recounted that Sarah had once told her that “her heart was full of dear old houses and dear old women, and that when an old house and an old woman came together in her brain with a click, she knew that a story was underway.” The house on South Berwick was the fountain of her stories.

The house transports visitors to nineteenth-century New England. On display is Captain Jewett’s imported furniture, silver, porcelain, tapestries, paintings, juxtaposed with the touches Mary and Sarah made when they inherited the house, such as a tulip-patterned wallpaper in the front hall. In the parlor Sarah entertained her Boston friends; books abound, as well as framed photographs of Annie Fields.

On the second-floor hallway is Sarah’s desk—originally her grandfather’s—where she wrote The Country of the Pointed Firs. Above the desk is a large window that overlooks the town square. The human comedy enacted outside her window became fodder for her novels. She would also have had a view of a stained-glass window and a glimpse into her garden. The desk holds innumerable objects, one of which is a quotation from Gustave Flaubert, “Écrire la vie ordinaire comme on écrit l’histoire,” which translates to “Write ordinary life as we write history.” The walls display portraits of literary figures George Sand and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. A copy of a poem, in Sarah’s handwriting, shares her admiration of her acquaintance Rudyard Kipling.

The heartbeat of the house is Sarah’s room that remains untouched since her 1909[mW1] death. Sarah had scratched her monogram into her window, the house’s sacred graffiti. The mantel over the fireplace is filled with bric-a-brac: books, candles, and a wood owl. In the center of the shelf is a photograph of a forever-young Annie. Due to the strategic placing of two mirrors, Annie’s image is reflected throughout the room.

A newspaper obituary referred to the passing of New England’s most eminent “woman writer”; the inclusion of the word “woman” is one at which Sarah would have taken umbrage. As she had once observed, “God would not give us the same talents if what were right for men were wrong for women.”

A View from Her Window

Sarah looked upon a garden filled with pear, lilac, and apple trees.