Was It Worth It?

The Prince of Denmark lashed out at Ophelia for wearing makeup that he equated with female deception, “God has given you one face and you make yourself another.” A twentieth-century cosmetic empire was likewise associated with duplicity, one not even its most artful of concealers could camouflage.

Women browse the cosmetic aisles, to capture attention, to recapture youth. Although the major names on the packages are iconic, most customers are unaware of the histories behind the labels. Every time one pulls out a compact, she pays silent tribute to Polish Jew Maksymilian Faktorowicz, cosmetician to the Russian royal court, founder of Max Factor. Nineteen-year-old Tom Lyle Williams watched his sister, Mabel, apply Vaseline and coal dust to her eyelashes, and Maybelline was born. And the world’s behemoth cosmetic company began with Eugene Schueller, chemist son of a baker. His genius: an instinct for knowing what makes women feel beautiful. In 1907, experimenting at his kitchen sink in his two-bedroom apartment, he developed the first hair dye that offered a variety of shades that he christened Aureale-the future L’Oréal. “This little bottle holds a huge industry!” he declared. “One day millions of brunettes will want to be blonde.” When a fair-haired Jean Harlow made golden tresses a fad by smoldering in the Hollywood hit Platinum Blonde, his prediction proved prescient.

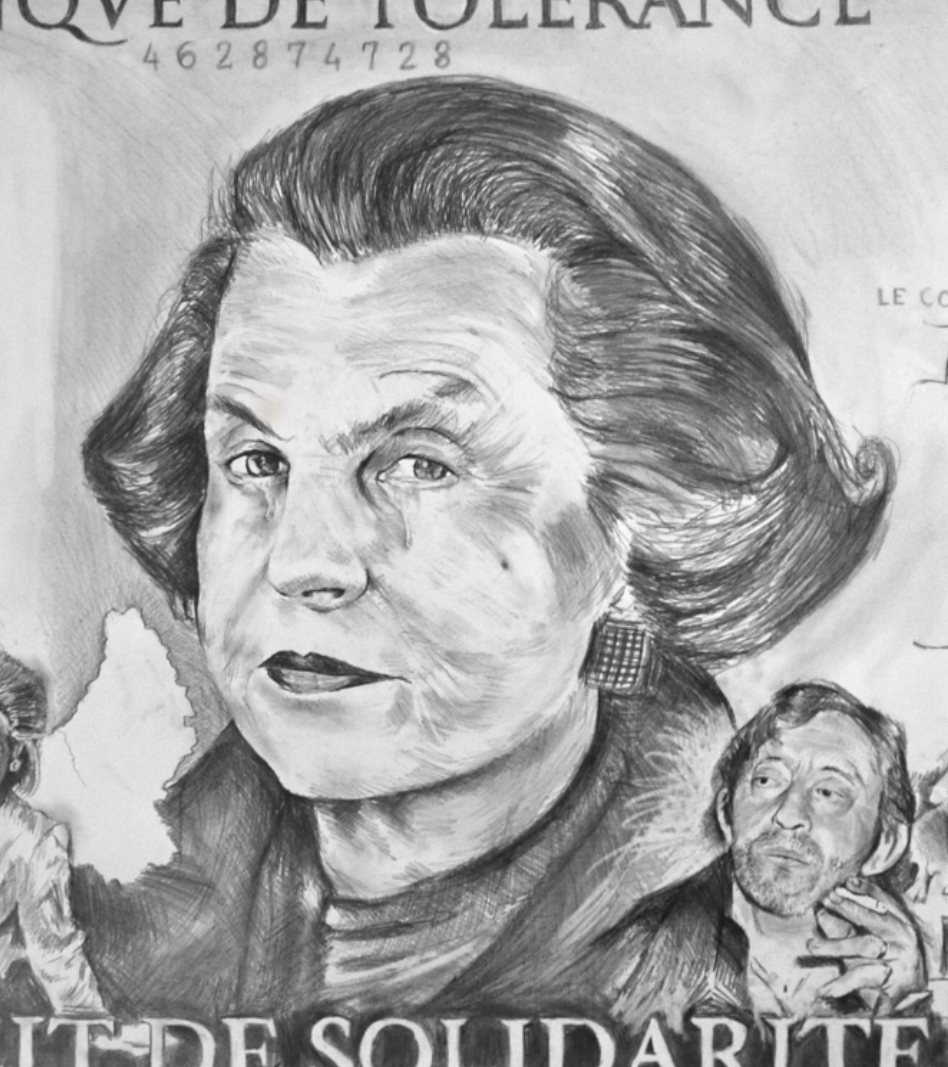

Eugene’s pianist wife, Louise, passed away when their only child, Liliane Henriette Charlotte, was five, and as the little girl was jealous of the women who circled around her wealthy father, his affection only extended to his daughter. At age fifteen, Liliane dabbled in the family business as an apprentice, her only hands-on encounter with the business that made her the heir to a fabulous fortune. The company was already a force to be reckoned with and distributed products in seven countries. Schueller acquired a chic Left Bank apartment and the trappings of wealth. During the Nazi Occupation, he also donned the mantle of collaborator in order to enrich his company’s coffers; its German headquarters was a confiscated Jewish property. Later Liliane defended her beloved papa with her explanation, “He was a pathological optimist who hadn’t the first idea about politics, and who always managed to be in the wrong place.”

In 1950, Liliane, a great beauty, wed Andre Bettencourt-another man who happened to be in the wrong place-he had worked alongside Schueller in La Cagoule, a virulently anti-Semitic group that busied itself in pastimes such as firebombing synagogues. L’Oréal’s’ Nazi past sadly answered Ophelia’s question, “Could beauty, my lord, have better commerce than with honesty?”

The Bettencourts settled in an Art Moderne mansion in Neuilly-sur-Seine that became the Mecca for Paris’s beau monde where politicians, financiers, and artists mingled under dazzling chandeliers and priceless art-adorned walls. In this milieu, Liliane and Andre raised a daughter, Francoise, born in 1953. As with her mother before her, an English governess was in charge of her upbringing; Liliane was never close with her daughter and described her as “a cold child.” With Andre at its helm, and with Liliane as chief shareholder upon the death of Eugene, L’Oréal acquired Helena Rubenstein, Maybelline, Lancôme, Ralph Lauren, and the Body Shop. With these plum packages and shares in the Swiss firm Nestlé, Liliane reigned as the ultimate Forbes-worthy heiress-to the tune of $39.5 billion.

In a nod to breaking with the family’s link to anti-Semitism, Francoise, the product of a staunchly Catholic household, married Jean-Pierre Meyers, who she met at the chic Alpine ski resort of Megeve and converted to Judaism. Andre was fond of telling people his daughter had “married an Israelite who likes us a lot.” Her two sons, Jean-Victor and Nicolas, had the unique heritage of a maternal grandfather who was a German collaborator and a paternal grandfather, a rabbi, who had been murdered in Auschwitz. Andre, who had written during the war, “The Jews their race is tainted with Jesus’ blood,” had long recanted, blaming his sentiments on the vagaries of youth. Whenever one pointed a J’accuse finger at the House of L’Oréal, Liliane kept her immaculately painted lips sealed.

By most accounts, the Bettencourts enjoyed a happy marriage in their mega-mansions; however, unlike other well-known heiresses whose notches on the crotch are appearances in the society pages, the world’s richest woman preferred the sanctity of the shadows. Her reticence may have been because of her innate shyness, fear of being the bull’s eye of kidnappers, apprehension of resurrecting a painful past.

After the 1997 passing of Andre, his eighty-seven-year-old widow intended to spend her twilight years in luxury and privacy, flitting between her luxurious homes: a sumptuous mansion in the chic Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, a luxury property built by her father overlooking the Brittany coast, and D’Arros, an isolated Seychelles Island enclave, purchased from Prince Shahram Pahlavi Nia of Iran. But the best-laid plans of mice and heiresses went awry when her tranquil twilight collided with the clatter of skeletons tumbling from her hangar-sized closets. The regal Bettencourt was appalled to find herself in a scandal dubbed L’Affaire Bettencourt, one far afield from her golden rule: never complain, never explain.

The key player in what became France’s greatest blood feud-cum-soap opera would surely surpass any Reader’s Digest Most Unforgettable entry. The chapter began with Francois-Marie Banier, a sixty-year-old photographer, possessor of Oscar Wilde wit and charm-as well as the Irish writer’s sexual persuasion. The names of legend had been his surrogate family: Salvador Dali, Yves St. Laurent, Pierre Cardin, Mick Jagger, and Johnny Depp; he was known to court celebrity widows. He captured on celluloid Samuel Beckett, Princess Caroline of Monaca (complete with shaved head), Lauren Bacall, Catherine Deneuve, and Truman Capote. As a fashion-house guru, he coined the name of Dior’s cologne Poison. Banier loved names; it soon became obvious he also loved money. The widow Bettencourt grew lonely for companionship which Francois graciously provided. She dubbed him her “enfant cheri,” and in return, Liliane gifted him-Mon Dieu!- 1.3 billion dollars in the world’s greatest goodie bag: paintings by Picasso, Matisse, and Mondrian, an island in the Seychelles, life insurance policies, and cash. What punctured Banier’s fortune-filled balloon was the Bettencourt butler. In the Paul Simon lyric-what the mama saw was against the law-and what the butler saw he also deemed illegal. Surreptitiously, he began taping exchanges between his boss and her BFF, using a tiny recorder hidden on his cocktail tray. He presented these to Francoise-along with the tidbit her mother was planning to adopt Banier- and the authorities charged him with abus de faiblesse, exploitation of the elderly. Mrs. Meyers’ opinion of the photographer was exemplified by the name of Dior’s cologne. Besides the exploitation, Francoise was hurt because her mother paid more attention to her companion than she had ever lavished on her own daughter. She also sought to have Liliane put under court-ordered guardianship. The French press had a field day-the two most reclusive and wealthy women in the world facing off, with the art-world enfant terrible of French society in the middle, filled realms of print. Liliane was infuriated and vowed nuclear war against her daughter to whom she swore never more to exchange a word. She said Francois had committed the ultimate sin: airing the family’s dirty laundry in public. She felt as it was her billions, bequeathed by her father, and she could do with the fortune as she wished. Liliane explained that without Francois-Marie’s friendship, charm, and intelligence she would have been imprisoned in the stiff, boring life of an elderly billionaire. She further explained her largesse by stating that Francois’s “friendship brought me intense pleasure and we did laugh like mad.” She went on the attack in the press stating of Bettencourt-Meyer, “My daughter could have waited patiently for my death instead of doing all she can to precipitate it.” Her attorney said he believed the case was less about money than about a dysfunctional mother-daughter relationship. He observed, “That Madame Bettencourt should have the misfortune of finding the brilliant Mr. Banier more amusing than her own daughter-and between you and me that’s no surprise-is not for this court to decide.” Banier, the Svengali at the eye of the storm, detained for thirty-six hours for questioning, when asked about the multi-million-dollar gift of the Seychelles Island testified he had never wanted it “because of its mosquitoes and sharks.” The court of public opinion thought Monsieur Banier the shark, as lethal as the maritime predator. However, he had his high-profile defenders such as Karl Lagerfeld, the king of Chanel and fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg. Their contention was it was the daughter, not Banier, who had violated the unwritten code of the Parisian beau monde: keep up appearances above all else. The scandal took its toll on Bettencourt whose skeletal frame appeared lost under the weight of massive pearl earrings.

With mother and daughter at war, it fell to Francois’s son, Jean-Victor Meyers, to serve as a diplomat between the two; it must have been daunting to be a twenty-something peacemaker and to have assumed the helm of a multibillion-dollar company. The fact he looks like a top European model, is heir to one of the world’s largest fortunes, and has access to every cosmetic and perfume one could desire, makes him a target for female Baniers.

Into every heiress’s life some rain must fall, and after a drought-free life, Liliane endured a torrential downpour. Besides the famous family feud with her daughter and the humiliation of appearing in the world press as a senile cash-cow, more storm clouds hovered. In the midst of having to prove her mental fitness, it came to light she had been the first investor in a fund managed by Rene-Thierry Magon de la Villehuchet who committed suicide in Manhattan after he had lost 1.4 billion dollars to Bernie Madoff, twenty-two million which had belonged to Liliane. Although the amount was paltry for Bettencourt, she was dismayed at the further mention of her name in the international press. And it was only to get worse.

The butler’s tape proved as damaging to Bettencourt as the Watergate tapes were to Nixon. Not only did it reveal Banier’s ever-escalating demands for gifts, but they also pointed a finger at French President Nicolas Sarkozy, whose love of luxury earned him the moniker the bling-bling president. His First Lady Carla Bruni, former lover of Mick Jagger, was none too averse to the green as well. The tape indicated Sarkozy was accepting huge envelopes of cash in exchange for the government’s decision not to scrutinize Bettencourt’s taxes. With the publication of these titillating excerpts from the tape that dripped words such as tax evasion and campaign-finance violations-just as Banier’s trial was set to start- any hope of public-relations damage control flew out the suddenly wide-open windows of Liliane’s Art Deco mansion. The heiress further transformed into the modern Job with the publication of Ugly Beauty and Bitter Scent that resurrected the back story of its fascist-fancying founder. It manifested the French novelist Honore de Balzac’s observation, “The secret of great fortune…is a forgotten crime.” Given the storms buffeting the House of Bettencourt, Liliane became the French Lear mumbling, “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child.”

L’Oréal’s famous catch-phrase, “Because I’m worth it,” can be converted into a tag-line for Ms. Bettencourt. Considering the associations of her billion-dollar empire that entailed a Nazi past, family feud, and exploitation, leads to the musing: Was it worth it?