Viva La Causa (1930)

Ironically, the World War II poster of Rosie the Riveter and its caption, “We can do it!” was the brainchild of a man though it became a symbol of female empowerment. In contrast, the slogan of the United Farm Workers, attributed to Cesar Chavez, was authored by a woman-one who history regulated to a footnote due to an amalgam of sexism and ageism.

Juliet, on her Verona balcony, concluded one’s name held no significance, yet this belief did not hold true for a baby born in the mining town of Dawson, New Mexico. Her parents, Juan and Alicia Fernandez, christened her Dolores, (Spanish for sorrow) and her 80 plus years has brought more than her fair share of heartache. She described her father as charismatic, intelligent, handsome, and a chauvinist, the latter of which contributed to the couple’s divorce when Dolores was three. Alicia took her children to Stockton, California, where she refused to follow the machismo mantra and raised her two sons and daughter as equals.

As a teenager Dolores’ passion was dance, and she received free lessons under the Works Progress Administration. Her aspiration was to one day become a professional dancer. This goal ended when her father, a former coal-miner who become a union leader and member of the New Mexico state legislature, piqued her interest in California’s exploited laborers. Her empathy had also been honed by the neighborhood immigrants who toiled under extreme heat for little pay and even less respect. Dolores determined the best way she could serve her community was through education and enrolled in the local University of Pacific’s Delta College teaching program. At age 20 she married Ralph Head, a manual laborer, with whom she had two daughters. In the classroom, she was appalled when students came to school hungry and in bare feet and determined she could make more of a difference as an advocate for reform. Committed to the cause increased after witnessing police brutality against workers who agitated for better wages. At age 25, she joined the Stockton Community Organization, a local group who lobbied for Mexican-Americans through political and civic engagement. Aided by her innate gift of oratory, and refusing to acknowledge the word no, Dolores became a voice for the voiceless. She founded the Agricultural Workers Association to protect the marginalized against the powerful-and ruthless-grape-growers’ interests. Despite her grueling schedule, she tried her luck at a second marriage with Ventura Huerta and the four children of their union joined her two daughters from her first marriage. An insight into Dolores as a young woman is apparent when a female reporter asked her what she would do if someone gave her $5,000 to spend on herself. She responded that she would donate it to the movement. When the journalist persisted and asked if she did not have the average woman’s dream of pampering herself, Dolores answered, “To me, being at a spa and having a new hairdo would be a terrible waste of time.”

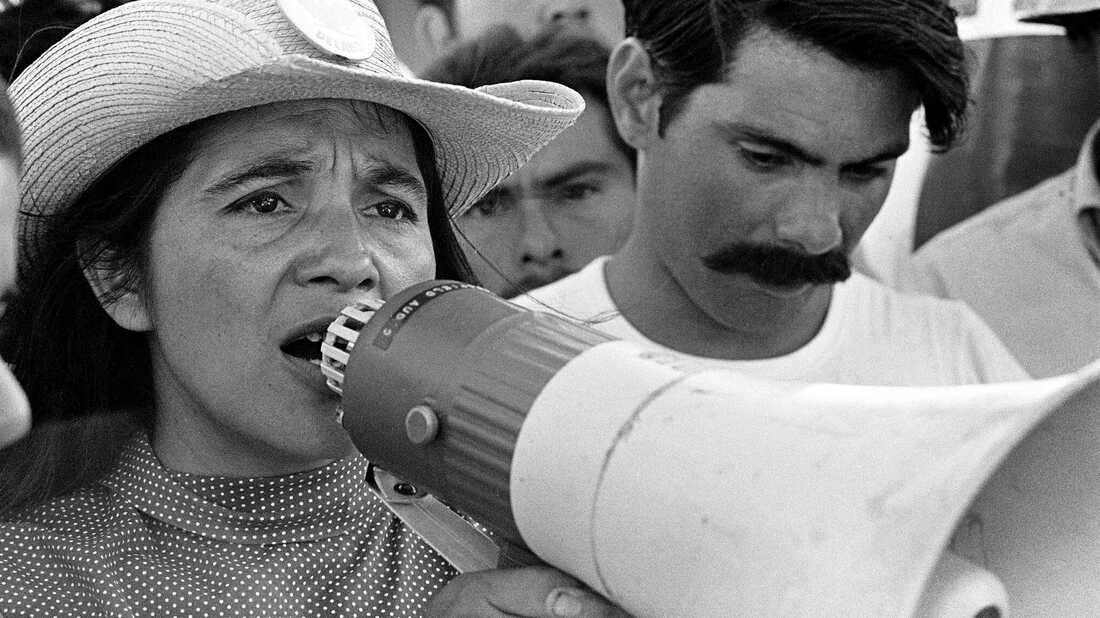

Dolores’ Marx meets Engels moment came with her introduction to Cesar Chavez; their common vision was galvanizing the oppressed. In 1962 they launched the National Farm Workers Association, a precursor to the later United Farm Workers. Three years later Dolores was a lead organizer for one of the most famous protests in US history- which lasted more than five year- the Table Grape Boycott They knew they could not succeed on their own and enlisted the conscience of the nation: 17 million Americans refused to eat grapes, lettuce, or Gallo wine. The little lady (she was 5’2”) faced off against powerful foes: the politically connected land-owners (who called her the dragon lady) California’s Republican governor Ronald Reagan, and President Richard Nixon. And yet David triumphed over Goliath. Their efforts bore fruit and resulted in the first contract between farm workers, growers, and the establishment of the United Farm Workers Labor Union. This victory was staggering: at the time this labor force-poor, and in many cases undocumented- were considered impossible to mobilize. They were subjected to horrific working conditions: wages as low as 90 cents an hour, and without toilets, cold drinking water, breaks, or protection from pesticides. Although the 36-year-old Dolores, rather than Cesar, had been the architect of the victory and who had exhorted women to join the struggle, these facts were expunged from the historical record. In all the iconic photographs, the workers are holding up the contract along with Chavez and the other male power players. Similarly, Cesar was given credit as the originator of Dolores’ iconic slogan, “Si se puede.” When Barack Obama used the slogan as a political rallying cry, Huerta’s name never came up. The former president righted the wrong in 2012 when he awarded the leader the Medal of Freedom and joked, “Dolores was very gracious when I told her I had stolen her slogan.” Although Chavez passed away in 1993, he still eclipses Huerta as the one who launched the movement, and there are countless monuments, street signs, and a holiday dedicated to the hero of the workers. Angela Davis explains this historical white-washing, “The assumption was that Chavez was the leader, and she was the housekeeper.” Because of her sex, and because she was 63, the union refused to pass her the baton of leadership, although she had been its co-founder.

At the time, Huerta did not question this sin of omission; as a child of the pre-women’s lib movement-despite her liberal upbringing-she still bought into the supremacy of the patriarchy. This mindset was altered in the late 1960s when she went to New York and worked with Gloria Steinem for the nationwide grape boycott and met other power-house women such as Angela Davis. When she returned to California, she was no longer willing to buy into the time-honored protocol of male supremacy and was determined to take credit for her accomplishments. Dolores also left an impression on Ms. Steinem who stated, “I know she set me on fire about racial injustice. I would not be able to see what’s hidden in the fields of our country without Dolores.” Awakened to gender inequality, Dolores later referred to herself as a born-again feminist when she revised her views on abortion. As a Catholic she had always eschewed the procedure; however, after her exposure to Women’s Liberation, she felt it a constitutional right to have control over one’s body- free from governmental control. She felt the pro-choice movement was important for the Latina field laborers whose large number of offspring ensured lives of dire privation. She expressed her views, “As Coretta Scott King said, we won’t ever have peace in the world until women take power. And when I say the word women, I may as well use the word feminist. Not all women are feminists, but feminists are people that care about immigrants and workers and the environment and labor rights, and of course reproductive rights, LGBT rights.”

When Dolores’ second marriage collapsed, she began a relationship with Richard Chavez, Cesar’s younger brother, and the couple decided the best way to help the workers was to live among them. Her opponents-including the Teamsters- tried to shame her for having 11 children with three different men –four born out of wedlock-and for the fact that she was not at home looking after them. These allegations proved hurtful as Dolores was always confronted with her own version of Sophie’s Choice: spending time with her family or fighting for her cause. When interviewed her children recalled with a mixture of pride and pain of the sacrifices they were forced to make as Dolores was often the mother of thousands rather than one to them. Her daughter said she was always “off and running;” a son revealed that it took ten months for her to realize that he had dropped out of high school. Another rued, “The movement became her most important child. There are scars because of that.” Dolores explained the reason behind her activism, “It was such a calling. I felt it so strongly. This is the reason I live.”

Unfortunately-like old habits-prejudice is hard to shake. In 1988 presidential candidate George H. W. Bush was speaking at a fundraiser at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. For the firebrand activist, then 58, it was just another day at ‘the office’; she was handing out leaflets on the UFW’s long-standing grape boycott, something she had done on countless occasions. However, this time the police moved in. A baton struck the diminutive protestor, shattering her ribs and rupturing her spleen. Her injuries required emergency surgery, and she was hospitalized for a month. The assault was captured on video, and her lawsuit resulted in a significant settlement and police department reforms. It did not, however, end her mission. In a speech she made her plea, “Sisters, brothers, feminists, all of us, we have got a lot of hard work to do. When Dr. King was at that great march in Washington, he said to the people at that great march, ‘Go back to Alabama. Go back to Mississippi. Go back and organize.’ This is the message I want to say to all of my sisters and brothers. We’ve got to organize.”

Until 2017, Ms. Huerta was one of the most important freedom fighters most people had never heard of. This situation changed with the release of the documentary Dolores that aimed to put her where she belongs-alongside Malcolm X, Dr. King, Cesar Chavez, and Gloria Steinem as one of the most important of American agitators for reform. The film debuted the night before women across the world marched for equality and human rights. Dolores was at the protest; after all, where else would she be? In Park City, Utah, she spoke at a rally following a march organized by Chelsea Handler where she led a chant of “Si se puede.” For many in the crowd this rally was their first experience of public demonstration; Dolores had been doing it for seven decades.

The documentary was the brainchild of guitar god Carlos Santana who served as executive producer. His mother, Josephina Barragan de Santana, had been insistent her son shine a long overdue spotlight on the 88-year-old activist who had given her blood, tears, and sweat to better the lives of the marginalized. When he heard the story of Dolores, he called her the real life Wonder Woman. He added, “I would like to see Dolores Huerta parks, libraries, freeways, schools. I would like her to have her own TV channel, running 24 hours a day.” It was a soft sell to get the producer Peter Bratt, the brother of the actor Benjamin Bratt, on board as the director was the son of a Peruvian-born mother who had marched with Dolores. Fortunately, a wealth of archival material showed her in action in the trenches throughout six and a half decades. Bratt refers to Dolores as the Forrest Gump of activism because of her connection to some of the great movers and movements of her era: in 1968 Robert F. Kennedy honored her moments before his assassination at the Ambassador Hotel, she was a participant in Black Lives Matter and Standing Rock protests. Cesar Chavez used to say, “The only time you lose is when you quit,” and though Dolores is approaching her ninth decade, quitting is something she does not intend to do. She must remain up and running as long as injustice remains.

As a girl Dolores had wanted to be a dancer, and in her fashion, she has achieved that goal. She has made activism an art form. Her remarkable life can be encapsulated in the words of a poster she once stood in front of, “Viva La Causa.”