The Next Morning (2005)

“My life is full of mistakes. They’re like pebbles that make a good road.” Beatrice Wood

8585 Ojai-Santa Paula Rd.

Ojai, California 93023

In medieval Florence, Beatrice Portinari served as Dante Alighieri’s guide in his masterpiece, The Divine Comedy. In 20th century California, Beatrice Wood inspired a pivotal character in James Cameron’s blockbuster, Titanic.

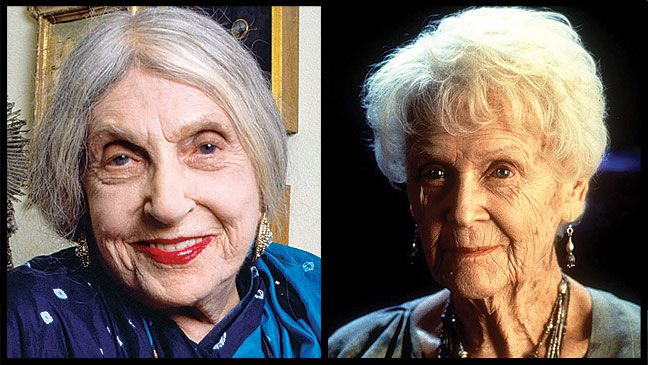

Upon reading Beatrice Wood’s autobiography, I Shock Myself, (written with the encouragement of author Anais Nin), Cameron contacted the author about using her life as the model for Titanic’s Rose Calvert. Her response, “Oh, I couldn’t possibly do that because I’m only 35.” She was 102 at the time. He also suggested Beatrice play the role of the elderly Rose but due to her hearing loss she declined. Illness prevented ceramic’s grand dame from attending the movie’s premier. On her 105th birthday, Cameron presented Beatrice with a pre-movie release VHS. She later admitted that she had not finished the film because of its tragic ending and “It was too late in life to be sad.” As she had watched the beginning, Beatrice saw her celluloid counterpart interrupted while fashioning a ceramic bowl by a program dedicated to the doomed ship.

A bohemian was born in 1893 in San Francisco; when Beatrice was five, the Wood family moved to an exclusive zip code on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Her childhood entailed a year in a convent school in Paris, enrollment at a finishing school, and summer trips to Europe. Accepting that her headstrong daughter’s dream was to become a painter rather than a trophy wife, her mother sent her-nanny in tow-to France to study at the Académie Julian. Never short on nerve, she peered through a hedge to watch Claude Monet painting in his Giverny garden. (In the Titanic, Rose mentioned Monet as Jack painted her wearing nothing but the magnificent gem, The Heart of the Ocean.) Switching her passion to theater, she departed for Paris and shared the stage with Sarah Bernhardt.

With the gathering storm clouds of World War I, Beatrice returned home and continued her acting career. While visiting a friend in the hospital, she met Henri-Pierre Roché, a writer who became her first lover. Her romantic cross was she “was a monogamist woman in a polygamous world.” Her next relationship was with Marcel Duchamp, best known for his painting, Nude Descending a Staircase. Through him she became a regular guest of the exorbitantly wealthy art patrons, Walter and Louise Arensberg.

Roché, Duchamp, and Wood published the avant- garde journal The Blind Man that led to Beatrice’s appellation, “the Mama of Dada.” Her father railed it was “a filthy publication,” and warned her that if she distributed the smut by mail she would end up behind bars like the birth control activist Margaret Sanger. Beatrice’s acclaim spread further after Roché’s novel regarding an amour a trois, Jules and Jim, inspired Francois Truffaut’s 1961 film of the same name where actress Jeanne Morea played the role of Beatrice. She denied she was involved in a love triangle with Roché and Duchamp and maintained she was a serial monogamist.

At age twenty-three, to escape her mother’s meddling, she eloped with her friend Paul Renson, a theatrical manager, and they departed for Montreal, Canada. The relationship was one of convenience and was never consummated. Paul also looked upon his wife as a convenience as her savings supported his gambling. An annulment followed as Paul had a secret wife and child in Belgium. Beatrice returned to the Big Apple; however, the worm in its core was the Dada Movement had died down, Marcel was travelling in Europe, and Roché had returned to Paris. In 1938, after her boyfriend, British director Reginald Poole, married an eighteen-year-old, she decamped for Los Angeles. In the belief that the Red Cross granted more sizable relief to married couples, Beatrice married her friend Steve Hoag, after a flood destroyed their house. She wrote in her autobiography, “I never made love to the two men I married, and I did not marry the men I loved. I do not know if that makes me a good girl gone bad, or a bad girl gone good.”

To be near her disciple, the Indian guru Krishnamurti, Beatrice found her forever home in cacti-covered Ojai, California, that she partially financed from the sale of a Duchamp drawing. Eventually, the guru, Aldous Huxley, and Beatrice founded the Happy Valley School that had a no grades policy. Her last passion was with an East Indian scientist with whom she fell in love at age sixty-eight on a trip to India. He said of their love affair’s end, “our trains move in opposite directions.”

While in Holland to hear her guru lecture, Beatrice purchased a set of baroque dessert plates; unable to locate a matching teapot, she decided to fashion one on her own. Her pottery held shades of Dada, were highly erotic, and satirized social hypocrisy. Endlessly experimental, she remarked, “Knowing what one’s about to take out of a kiln is as exciting as being married to a boring man.” She signed her pieces with her nickname, Beato.

Visitors to Beatrice’ studio saw the barefoot centurion ceramist with hip length hair in a long, thick braid, sported a challenging amount of silver and turquoise jewelry, wore rings on scarlet-painted toes, dressed in brightly colored saris. When asked about the key to her longevity, she attributed it to “art books, chocolate, and young men.” Governor Pete Wilson of California declared her a “California Living Treasure.” Forever youthful in terms of romance, Beatrice shared, “I still would be willing to sell my soul to the devil for a nice Argentine to do the tango with.” The legend had befriended Brancusi, danced for Nijinsky, made costumes for Isadora Duncan, and had shared a gynecologist with Edna St. Vincent Millay. Beatrice’s birthday bash drew 250 guests, among them were James Cameron and Gloria Stewart who had played the role of the elderly Rose. The national treasure passed away shortly afterwards. Devotees scattered her ashes among Ojai’s Topatopa mountain. She left her property to the Happy Valley Foundation that eventually transformed into the contemporary museum.

The Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts promotes self- expression through the mediums of ceramics, painting, music, film, photography, and woodworking. The gallery also preserves her legacy through her pottery, international collection of folk art, extensive library, and healing crystals. The sign on her studio door remains, “Reasonable and Unreasonable.” Her bright pink mailbox holds the logo of The Blind Man thumbing his nose.

The photographs of Beatrice Wood provide a visual diary of the original hippy chick. One is dated 1917, taken in Coney Island. Beatrice is seated on a fake ox, Duchamp behind her in a cart. Of the magical memory Beatrice wrote, “With Marcel’s arm around me I would have gone on any ride into hell with the same heroic abandon as a Japanese lover standing on the rim of a volcano ready to take a suicide leap.”

Rose Calvert’s home also held photographs-showcasing all the adventures Jack had envisioned for her future. The difference between Beatrice and her celluloid counterpart is while Rose had found her grand passion, true love had proved elusive for the artist. She rued the Topatopa Mountain was the only partner she could ever count on “to be there when I go to bed at night and still be there when I wake up the next morning.”