The Lady and the Tramp

Charlie Chaplin’s character of the Little Tramp became an immortal icon for his deft portrayal of man’s tragicomic conflict with fate. The lonely fellow buffeted by life resiliently picked himself up again and again in the hope that the next encounter would turn out better. And what made the man behind the clown stop leaning on his famous cane and throw it heavenward was the love of his lady, whose story has slipped through the crack of time until now.

This woman, who embodied American royalty both through birth and marriage was lost behind the giant shadows cast by two larger than life men. Her father, Nobel Laureate Eugene O’Neil, met her mother, Agnes Boulton, in a Greenwich Village Bar, the Hell Hole, a name laden with foreshadowing of their life together. Their first child was son Shane and second was daughter Oona, born on May 14, 1925, in Spithead, an oceanfront home in Bermuda. Her unique name derived either from the anglicized version of Juno or the Irish word for lamb. Despite the couple’s commonality of children, writing and alcoholism, Eugene deserted his second wife to marry his third, actress Carlotta Monterey, who could have served as role model for a Disney stepmother. Growing up without a father left Oona with a lingering emptiness, and throughout her life she tried to cling to a father-daughter relationship.

O’Neil, notoriously tight-fisted, would have preferred the removal of an impacted molar to coughing up child support. Nevertheless, he agreed to finance Oona’s education at Manhattan’s exclusive Brearley High School. It was during these years she made the acquaintance of life-long friends Gloria Vanderbilt and Carol Marcus. The girls had the common denominators of striking beauty and were, through death or desertion, fatherless. The charmed circle later became the muses of their friend, Truman Capote, and served as collective inspiration for the character of Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

On a visit to her mother’s Point Pleasant New Jersey home Oona was introduced to Jerry, an aspiring young writer who became her first boyfriend. Their courtship was interrupted when he enlisted after Pearl Harbor but wrote letters of longing from overseas. Oona became the princess of the Stork Club and was crowned Debutante of the Year. Dazzled by the limelight, she turned down acceptance to Vassar for the silver screen. She travelled to California, accompanied by Carol who was on her way to marriage with writer William Saroyan whom she was to divorce and remarry before achieving lasting happiness as the wife of Walter Matthau.

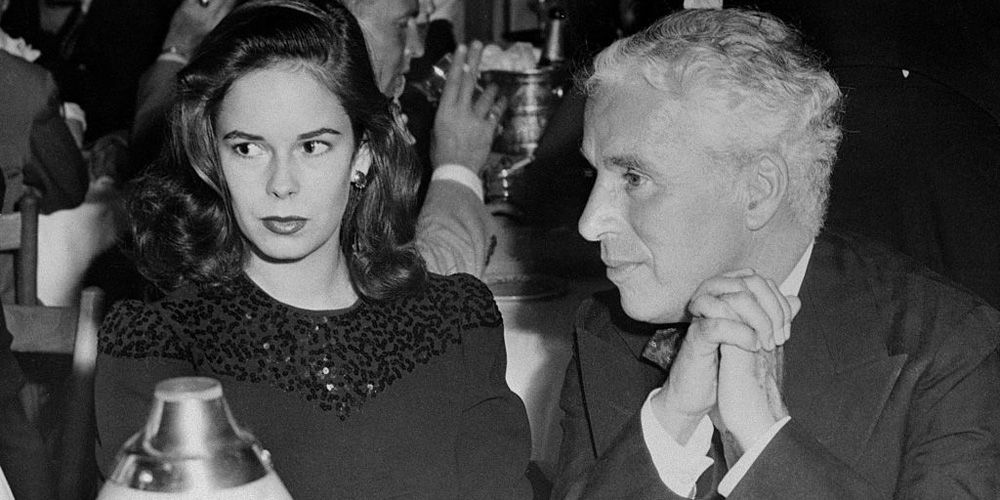

Oona also acquired her own prominent escort, Orson Welles, as well as agent Minna Wallis who thought she would be perfect for a role in Charlie Chaplin’s film Shadow and Substance. Minna called the director, her friend, and asked him to her home to meet the fledging starlet. He agreed though with the feeling that the daughter of O’Neil would be bleak and spend the evening searching for a ledge. Instead, in his search for a screen heroine he met his romantic one. After their fateful meeting, Oona had an inkling she’d landed the greatest role of her life. In a letter to Carol the seventeen-year-old gushed she had just met Charles Chaplin and “what blue eyes he has!”

An impediment to their three-decade romance was though that Chaplin’s legendary screen persona, the Little Tramp, was his off-screen one as well. By the time of their meeting, Hollywood’s most energetic actor/director had successfully batted those baby blues at half the female population of California. When this came out, the paparazzi were ecstatic and embarked on a feeding frenzy. But not everyone shared their joy. Eugene was infuriated his daughter was considering marriage with a man the same age as her father; whose three former marriages had quick expiration dates; who was involved in a paternity suit; and who had leftist leanings. He wrote that if she walked down such an aisle he would end all future contact.

Another irate letter arrived, one from her boyfriend Jerry regarding her betrayal. Their courtship officially ended when Oona chose the Tramp over the creator of Holden Caulfield. It was perhaps in ire against Charlie when Jerome (“Jerry”) David Salinger published his later novel, Catcher in the Rye, with his protagonist Holden Caufield stating, “If there’s one thing I hate it’s the movies. Don’t even mention them to me.”

In contrast to all the naysayers, Oona’s mother, Agnes, was delighted with a marriage which could provide her daughter with enormous wealth, the company of the world’s most famous, and drive a stake through her ex-husband’s heart to boot.

A nuptial veteran, Charlie knew how to elude the eye of the storm and the couple fled up the coast to Carpenteria, near Santa Barbara, where they were wed in a private ceremony. Oona’s stock reply when asked about their thirty-year age difference, “Charlie has made me mature and I keep him young.” Such sentiments led to actress Joan Collins’ observation that Mrs. Chaplin was an American geisha. Apparently, Oona was more a lamb than Juno.

When Charlie carried his bride over the threshold of 1085 Summit Drive she entered a magnificent six acre estate on a hillside overlooking Beverley Hills, in close proximity to Pickfair, the mansion owned by Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. The couple initiated Sunday Open House where the glitterati were invited for tennis, dining and company never guilty of Oscar Wilde’s one unforgivable sin: to be boring. In Hollywood, an invitation to the Chaplins’ was analogous to Queen Elizabeth summoning one for Buckingham Palace afternoon tea. Typical guests included Noel Coward, Thomas Mann, Evelyn Waugh, and Albert Einstein. Presiding over the court the tramp traded his cane for a scepter, and no one hung onto his words more fervently than his worshipful spouse. Soon the estate, serviced by a full-time staff of ten, included four adored children.

However, a storm cloud was gathering on the blue Hollywood horizon. During the witch-hunts of the 1950s HUAC turned its spotlight on the Little Tramp. Chaplin, who had grown up in the slums of London, championed Leftist causes and was a vocal critic of the Cold War government. Charlie insisted he was a comedian, not a Communist, but Washington believed otherwise. To distance himself from unwelcome scrutiny the director decided to attend the London premier of his film Limelight and to show his wife and children the city of his birth. On the second day of their sea voyage aboard the Queen Elizabeth, the Chaplins were dining with pianist Arthur Rubenstein when Charlie received a telegram stating he would be barred from re-entry to America until he could prove ‘moral worth.’ Infuriated, Chaplin told Oona he was a political martyr and would never return to the United States which, by extension, would make her a stranger to her own country. Oona agreed and refused to look back; her allegiance never faltered. She stated, “He is my world. I’ve never seen or lived anything else.” In 1953, in solidarity, she renounced her American citizenship and became a British subject.

The Chaplins found their final home in Switzerland in an 18th century, fifteen room mansion, on forty acres-the Manoir de Ban, ample space to raise their eight children. Its panoramic view encompassed a view of Lake Geneva and the Alps. It became an intellectual watering hole with visitors such as Pablo Casals, Nikita Khruschchev, Jawahaarlal Nehru, Yul Brynner, Carol and Walter Matthau, and Gloria Vanderbilt. The children were overawed by the arrival of Truman Capote who was dressed toe to neck in red and managed to thoroughly irritate their father. They also entertained neighbors who comprised a Who’s Who of exiled royalty, including the former king and queen of Italy. However, most evenings consisted only of the Swiss-Family Chaplin, where the chatelaine would hold hands for hours with her husband while the children were attended by governess variations of Maria von Trapp. Chaplin stated, “My wife and children are more important than all the publicity in the world.” In his eighties the spotlight of publicity once again fell on the aged tramp who had bequeathed to the world humor and humanity.

In 1972 Charlie broke his twenty-year exile from the United States to receive an honorary Oscar. The theater darkened to play clips of his classic films and when the lights turned on and the audience saw their returned clown prince, he received the longest standing ovation in Oscar history accompanied by cheers of “Charlie!” There was not a dry eye in the house when Jack Lemmon presented him with his iconic hat and cane-and the most copious tears were from Oona. Another great honor followed three years later when Queen Elizabeth II conferred knighthood on the Little Tramp and the couple became known as Sir Charles and Lady Oona.

There is a saying it is not wise to let too much light into the castle and this held true for the Manoir de Ban. Although Oona seemed to have an enchanted life with her fairy-tale marriage, eight children who were the recipient of their mother’s beauty and their father’s fortune, the possessor of a magnificent estate replete with honorary Oscar and title of Lady, sorrow still infiltrated. She had named one of her sons Eugene but that still did not secure reconciliation with her father who died without a deathbed forgiveness. In his will he disinherited his only daughter and any of her issue. The O’Neil curse also claimed her brothers: Eugene Jr. committed suicide in his bathtub and Shane plunged to his death from a window of a police station. Both of their deaths had been brought on by alcohol and drug addiction. Her mother Agnes died in squalor, her Pleasant Point home over-run with an army of cats who had soiled every available surface of Oona’s childhood home.

The greatest of all heartaches came on Christmas Day, 1977 when Charlie passed away. Oona was in a realm beyond bereft and was known to sit holding Charlie’s glove. The anguish of his passing was compounded when grave robbers stole her husband’s corpse and demanded a ransom. If not paid, one of her seventeen grandchildren would be harmed. The response brought out Oona’s Juno at last; she refused to give in to their demands, “A body is simply a body. My husband is in heaven and in my heart.” His remains were discovered in a cornfield and the farmer on whose land it was found consecrated the spot with a cross and a cane. Oona declared the tribute more moving than her husband’s official burial site.

After thirty years as the archetypal bird in a very gilded cage, Oona became a Merry Widow, trying to find escape through young lovers; one of these was David Bowie, another Ryan O’Neal. Gloria Vanderbilt’s comment on the latter liaison, “Ryan wanted to marry Oona just to make her an O’Neil again.”

Although that nuptial did not transpire, Oona did revert to being an O’Neil once more of her own accord: she slid into the arms of alcohol. Increasingly inebriated, Oona became a recluse in Manoir de Ban where she watched endless films of Charlie. In the silver screen she was able to dwell once more in the golden days of the lady and the tramp.