Riddles Unexplained (1901)

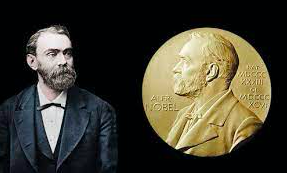

The Nobel Prize is arguably the world’s most acclaimed award. A few of the eminent recipients have been Rudyard Kipling, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama, and Nelson Mandela. Lost in the hoopla of the glittery event is the shadowy presence of inventor Alfred Nobel.

The man who left a legacy of a two-edged sword-he created dynamite and the the Nobel Peace Prize- peace-was born in Sweden in 1833, one of eight children of Immanuel and Andriette Nobel. When Alfred was nine, the family joined Immanuel in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he worked for Tsar Nicholas I in establishing naval mines during the Crimean War. With the advent of peace, Imanuel lost his wealth and the family returned to Sweden. Though Alfred’s ambition was literary, his father convinced him to follow in his scientific footsteps. Alfred worked in Immanuel’s factory where he focused on experimenting with nitroglycerine. Tragedy followed when a laboratory explosion killed Emil, the youngest Nobel son, as well as four workers. Undeterred, Alfred persisted with the result he invented an explosive he named dynamite. His 1866 brainchild changed the world: it led to the creation of the Panama Canal, it allowed trains to pass through mountains, it racked up the casualties of war. Dynamite also made the shy scientist exceedingly rich: he established ninety factories in twenty countries. Victor Hugo described him as “Europe’s richest vagabond.” Despite his Midas touch, Alfred suffered from depression. When asked for a brief biography for the Nobel family history, Alfred’s answer, “Greatest sin: does not worship Mammon. Important events in his life: none.”

However, there was an event that altered the trajectory of his life. In 1888, while in his French mansion, Alfred had the novel experience of reading his own obituary. The column stated, “Le marchand de la mort est mort” (The Merchant of Death is Dead). The paper went on to explain that the dynamite king had “become rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday.” In truth, it had been Alfred’s brother, Ludwig, who had passed away on a visit to Cannes, France. The shoddy journalism led to Alfred’s eureka moment: he would rewrite his will to alter his posthumous legacy so that a Marc Anthony would never say over his grave, “The evil that men do lives after them.” He earmarked his fortune of 35 million kroner (225 million in contemporary currency), to create an annual prize that would reward those “who during the preceding year shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.” The most famous last will in history consisted of 300 words, penned on a torn half sheet of paper.

When Alfred passed away in 1896 in his magnificent villa in St. Remo, on the Italian Riviera, the reading of his will sent shockwaves through Sweden with the intensity of a blast of dynamite. His disinherited family, infuriated, took the matter to court; Swedes were outraged that foreigners could become laureates. The Nobel committee set December 10th, (the anniversary of Alfred’s death,) as the annual award date. In the inaugural ceremony, King Oscar II handed the gold medallion, bearing the profile of Alfred Nobel, to the winners, one of which was the German Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen, for his discovery of X-rays.

Alfred Nobel was a man of many of paradoxes: brilliant, he always felt inadequate, an advocate of peace, he had invented an instrument of war, a Swedish patriot who had lived abroad. His contradictions led to his verbal self-portrait, “You say I am a riddle-it may be, for all of us are riddles unexplained.”