Queen of Sugar Hill

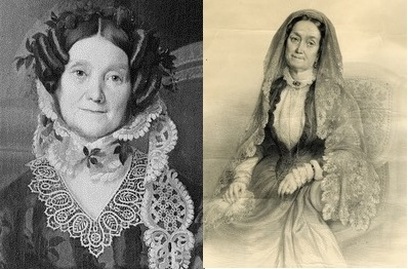

Eliza Jumel

“Vice Queen of the United States” (How Eliza Jumel introduced herself in Paris)

Morris- Jumel Mansion (opened 1904)

If walls could indeed talk, Manhattan’s ’s oldest remaining home would provide a tantalizing tale. And one would be of Eliza Jumel who defeated Aaron Burr in a duel. To experience the historic house that doubled as a nineteenth-century soap opera, head over to the Morris- Jumel Mansion.

While the Cockney Eliza Doolittle longed for “a room somewhere/far away from a cold night air,” the Yankee Eliza Jumel’s appetite increased with the eating. Her mother, Phebe, married sailor John Bowen, and gave birth to John Thomas, followed by Mary. Her youngest, Betsy, arrived three weeks before the start of the American Revolution. As her husband, away at sea, provided only a pittance, Phebe worked in a “disorderly house,” situated on the site of a former jail. When Betsy was seven, she awoke in terror as rioters burned down the brothel to rid Providence, Rhode Island, of its citadel of sin.

The homeless mother and daughters relocated to a shelter before they found lodgings with Patience Ingraham. Phebe and Patience ended up behind bars for “plying their flesh.” For the next three years, Betsy endured the workhouse until she became an indentured servant for Samuel Allen and his wife, Charlotte. Misfortune dogged the Bowens: John drowned at sea, and Phebe and John Thomas passed away, likely from yellow fever.

As an adult, Betsy moved to New York, where she worked as a stage actress. In a bid at reinvention, she transformed to Eliza Brown, a moniker possibly chosen for its association with the wealthy Brown brothers who founded Brown University.

The man who impacted Eliza’s destiny, Étienne Jumel, fled France at the outbreak of the revolution. In America, he anglicized Étienne to Stephen and fell for the actress. A week after Eliza’s twenty-ninth birthday, she married the thirty-eight-year-old Stephen. In the same spirit as Henry of Navarre’s philosophy, “Paris is worth a mass,” Eliza, a member of the Congregational Church, wed Stephen in a ceremony officiated by Father William W. O’Brien, the pastor of Manhattan’s only Roman Catholic church. Prominent New Yorker John Pintard wrote to his daughter that Eliza had tricked Stephen into marrying her by pretending to be terminally ill, and her dying wish was to be made an honest woman. The animosity stemmed as the era’s zeitgeist held that men of the mercantile class did not marry actresses with murky pasts. Later in life, for upper-class acceptance, she became an Episcopalian. Without children of their own, they raised Mary, Eliza’s illegitimate niece.

The Jumels purchased a bluff-side estate that had long stood empty—except for its gallery of ghosts. British Colonel Roger Morris and his Anglo-Dutch heiress wife, Mary, whose family had made their fortune in the slave trade, had built Mount Morris as their summer residence. When they left the city at the onset of the Revolutionary War, General George Washington commandeered the estate as his headquarters. He remained there for five weeks, and the second-story octagonal-shaped room served as his office till British troops necessitated his departure. For a brief period in 1790, when a tenant farmer, John Bogardus, rented the premise, the house transformed to an inn and tavern. At that time, Washington threw a lavish banquet on its grounds. His guests included Thomas Jefferson, John and Abigail Adams, Alexander and Eliza Hamilton, Martha Washington, and Major General Henry Knox, the latter the namesake of Fort Knox

Twenty years after the who’s who of American history dinner, Stephen and Eliza Jumel changed the name of Mount Morris to Mount Stephen. The Jumels purchased the property and its 104 acres for $9,927.50. Eliza managed to knock two thousand dollars off the price as local lore held a Hessian soldier’s ghost hung around the mansion’s stairway. Mary refused to stay alone in the house. Their real estate portfolio included property on Broadway, located three blocks from Wall Street, purchased for $14,700. Further acquisitions made the once penniless Eliza one of New York’s richest women. Their cook, Anne Northrup, was the wife of Solomon Northrup, author of Twelve Years a Slave. She worked as Eliza’s cook for one to two years in the 1840s.

To spend time with Stephen’s family, the Jumels boarded the Maria Theresa for France. In Paris, over the next eighteen months, Eliza purchased more than 240 paintings that dated from the sixteenth through the early nineteenth century. Souvenirs of her travel abroad were the works of art, armoires, sofas, and chairs. When she returned to the States, what she left behind was Stephen Jumel. Despite the distance, Stephen’s matrimonial fire remained strong. He wrote to his wife, “Since your departure, my bedchamber has become insipid to me. I stayed on the jetty until I could no longer see the ship.” Stephen granted Eliza power of attorney to handle business transactions during his absence. Her real estate investments and aggressive lawsuits increased their fortune.

A relationship that remained constant throughout Eliza’s life was the one she shared with Mary. Eliza gave her blessing when her attorney, Nelson Chase, married her niece. Nelson might have been partially attracted to the fact that Mary was an heiress. Stephen, who had returned from the continent, acted as witness. Shortly afterwards, travelling in a one-horse wagon, he suffered a fatal fall. The story that made the rounds was Stephen’s death had resulted from impaling himself on a pitchfork and the missus had intentionally not bandaged his wounds. In either scenario, Stephen expired at his namesake home, leaving the fifty-seven-year-old Eliza a widow. His passing resulted in a famous addition to Mount Stephen’s guest book.

Nelson began working for attorney Aaron Burr, whose curriculum vitae included a stint as Thomas Jefferson’s vice president and the killer of Secretary of State Alexander Hamilton. Eliza invited Burr to Mount Stephen for a banquet, and he charmed his hostess when he led her to seat with the words, “I give you my hand, Madame; my heart has long been yours.” Burr proposed with a Machiavellian agenda: as he was always in debt, he felt Eliza was the key to an economic kingdom. The widow’s calculation was that marriage to a former vice president would bring her entry into the societal circle for which she had long sought entry. They were wed in her home’s front parlor.

The matrimonial bubble burst when Eliza grew alarmed at the rate at which her husband was going through her fortune. Eliza’s divorce lawyer was Alexander Hamilton Jr., who may have hoped he would win the case in a bid at karmic retribution. A judge dissolved their marriage in 1836, a few hours before Burr’s death. His passing freed Eliza from her inconvenient second husband and allowed her to present herself as the widow of the vice president. On this occasion, gossip needed no embellishment. The saga of Betsy Bowen, Eliza Brown Jumel Burr, ended when she died, alone, at age ninety, at Mount Stephen. The woman who had started life in a brothel passed away as one of America’s wealthiest women, and the country’s first major collector of European art.

Morris Jumel Mansion

Constructed in 1765, the Morris Jumel Mansion is Manhattan’s oldest remaining home whose age alone renders it a revered address. The estate’s senior status, along with the fact that presidents, first ladies, and a vice president walked its halls, makes it a notable landmark. Gazing at the balcony, one can visualize George Washington pacing its length, contemplating a strategy to drive the British back to their shores. Contemporary accounts hold that Eliza, a Manhattan Miss Havisham, suffering from dementia, rode around her property on horseback, attended by a contingent of homeless men, armed with sticks for rifles, in a mock parade. The Entrance Hall holds a painting of the chatelaine, along with her two grandchildren, commissioned in 1854 while in Rome. In case one wanted to sit and gaze upon her portrait, there is a sofa upholstered in gold with claw feet. Another canvass is of the evicted Aaron Burr. In the parlor, adorned with light blue brocade, lies the furniture Eliza maintained had once belonged to Napoleon. A French Empire armchair, carved with a floral motif, has engravings of dolphins, with an upholstered seat and back. Equally ornate, the pianoforte displays a brass lion head. The dining room holds a French porcelain basin with a blue floral decoration. A French style candelabra with three candles rising from a laurel wreath held aloft by a figure of winged victory resting on an orb is an embellishment of the Octagon Room. From the wall of the Octagon Room is an oil painting of the mistress of the manor whose brass plaque reads: “Eliza Jumel 2nd wife of Aaron Burr Vice President of the United States.” On the second floor is Eliza’s bedroom which holds a canopied bed with a covering of navy fabric. Aron Burr’s room retains a cast iron bootjack in the shape of a beetle, and his gaming table.

When Roger and Mary Morris constructed their summer home, an architectural flourish was a grand Tuscan portico. The Georgian-style mansion, situated on the second highest point of Manhattan, is reminiscent of a Southern plantation, a Tara transplanted to the East Coast. In 2014 writer and composer Lin-Manuel Miranda sat in Aaron Burr’s bedchamber where he wrote songs such as “The Room Where It Happened” for his hit musical, Hamilton.

Visitors come to gaze upon rooms that exhibit furniture from various time periods, including Second Empire pieces that Eliza brought from France. Aaron Burr’s writing desk holds several cubbyholes. Eliza’s is buried five blocks from her old haunt, in the Jumel mausoleum in Trinity Cemetery.

In the 1930s, Duke Ellington moved into the area referred to as Sugar Hill, and pronounced the Morris- Jumel Mansion its crown jewel. Eliza Jumel reigns as the queen of Sugar Hill.

A View from Her Window

Looking out at her domain, Eliza would have had views of the Harlem and Hudson Rivers, Westchester County, and Staten Island.

Nearby Attraction: The Apollo Theater