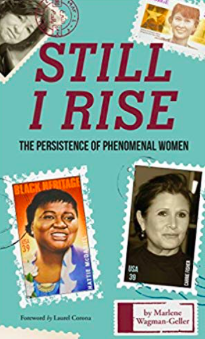

Prologue Still I Rise

Jun 23, 2019 by Marlene Wagman-Geller

Anyone who has managed to survive to mid-mark of the biblically allotted three score years and ten has had occasion to cast one's eyes heavenward to mutter, "Ya know, God, there are other people." Amidst these litanies of woes can be discerned cries of betrayal, illness, lost illusions. After all, part and parcel of living means treading the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, navigating the Canal of a Shattered Romance. What helps ease the thorny path is the belief that we are not alone in our grief, that loss is part of the human condition. Another weapon in the arsenal of endurance is the hope we can rise.

Anyone who has managed to survive to mid-mark of the biblically allotted three score years and ten has had occasion to cast one's eyes heavenward to mutter, "Ya know, God, there are other people." Amidst these litanies of woes can be discerned cries of betrayal, illness, lost illusions. After all, part and parcel of living means treading the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, navigating the Canal of a Shattered Romance. What helps ease the thorny path is the belief that we are not alone in our grief, that loss is part of the human condition. Another weapon in the arsenal of endurance is the hope we can rise. In a nod to the sweet is sprinkled with the bitter, while celebrating the launch of my fourth book, Behind Every Great Man, was the pain I experienced from watching a lady I love grappling with a tsunami of tsoris, which, through solidarity, became my own. For solace, I turned to women who had conquered their own emotional Everests; who had not only not been crushed but prevailed. The first of these possessors of indomitable spirit I investigated was Hattie McDaniel. She was the thirteenth child born to former slaves, and her life was a Sisyphus-like struggle against grinding poverty, racism, four failed marriages, and a hysterical pregnancy. Rather than bowing to defeat, she arm-wrestled Jim Crow and broke the color barrier in film to become the first African-American to win the Academy Award for her portrayal of Mammy in Gone With the Wind. In her emotional acceptance speech, she stated she hoped she was a credit to her race. She was-and not just to her race, but the human race. Aung San Suu Kyi went from fifteen long years of house arrest in Burma to Sweden's Nobel Peace Laureate. Rather than vow vengeance on those who had stolen her life, she sought to negotiate with the junta, something that bore no fruit. She stated with her indefatigable humor sweetened with temperance, "I wish I could have tea with them every Saturday, a friendly tea. And, if not, we could always try coffee." Nobody feels sorry for London born Joanne Rowling, the most staggering successful author. However, her earlier life was a prologue far removed from her present golden years. She was in Portugal, trapped in a physically and emotionally abusive marriage, mother of an infant when she fled penniless to her sister's Scottish home. Had she succumbed to the depression which had led to the contemplation of suicide, the world would never have met its beloved, bespectacled wizard. Although these ladies hailed from different climes and chronologies, they shared a common denominator. Life had thrust them to their knees, but there they refused to remain.

In addition to writing the book as a paean to the ladies who, rather than letting all obstacles smash them, they smashed all obstacles, was the fact that historically men seem to have garnered the monopoly on transcending suffering. One needs only to think of the Bible, and the men engaged in epic struggles: Jonas adrift in the whale's belly, Moses' grief upon smashing the Ten Commandments, of Christ on his cross. From the modern era are the images of the jailed freedom fighters: Mandela in South African, Gandhi in India, King in America. Their female counterparts have somehow been obscured, although their sufferings were no less, their courage no less.

In my inbox, I often receive emails from friends concerning female empowerment, of the solidarity of sisters. Still I Rise is an extension of these cyber-hugs. My hope is these stories of courage will give faith to those who falter for there is truth to the might of the pen. Nelson Mandela, while a prisoner of Apartheid on Robben Island, kept in his cell the inspirational poem "Invictus." The poem was a kind of Victorian Sinatra "My Way," about one's head being bloody but unbowed, of possessing the fortitude to remain captain of one's soul.

The verse from which I took the title of this volume was penned by the intrepid Maya Angelou whose life was a patchwork quilt of challenges. She had been the victim of a childhood rape whose trauma left her without a voice for several years, failed marriages, and racism. Yet, through the elixir of words, she broke free from the solitude of silence and became the poet laureate of President Bill Clinton's Inauguration. Through her travails, she discovered why the caged bird sings-it sang because though imprisoned, it never lost the vision of a life free from bars. In an ode to her indomitable spirit she wrote an anthem of fortitude:

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may tread me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.