Minerva

“I am not certain if I can. At least I’ll gladly try.” Betsy Ross

The Betsy Ross House (opened 1937 )

239 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Within the stripes of the American flag lies a treasure trove of history, mystery, and controversy. “Old Glory” appears in fifty states and on the moon; thousands have died fighting for or against it. The Marines raised the Stars and Stripes to commemorate the victory in the Pacific; the draft-dodgers burned it in protest of the military in Southeast Asia. As the Twin Towers crumbled, three New York City firefighters rigged a makeshift flagpole and hoisted the symbol of resilience. Millions visit the Betsy Ross Home to pay homage to the universal icon.

Beneath the legend is Elizabeth, (Betsy,) born in 1752 in Gloucester City, New Jersey, one of seventeen children of Samuel and Rebecca Griscom. The family were members of the Society of Friends, known as Quakers-so called after members quaked in church. When Betsy was three, the family relocated to Philadelphia where Samuel worked as a carpenter.

A person who left a lasting impact on Betsy was her paternal great-Aunt Sarah who operated a business that fashioned women’s corsets. She taught Betsy how to sew and showed a woman could be her own boss. When Betsy visited her sister, an employee at an upholstery shop, the eleven-year-old fixed an issue that a seasoned seamstress could not, store owner John Webster offered her a six-day-a-week apprenticeship. From that point Betsy’s education ended, and her seventy-year vocation began.

Betsy remained in her position until she fell in love with fellow apprentice, John Ross. Although John had established his own business and was a member of a well-connected family-his uncle, John Ross, was a member of the Continental Congress- the thorn in the romance: he was Anglican, and the Society of Friends forbid intermarriage. Consequently, John and Betsy eloped; they crossed the Delaware River to nearby Gloucester, New Jersey, where they wed in a local inn named Hugg’s Tavern. Betsy joined her husband in worshipping at Christ Church where General Washington attended when he was in Philadelphia. The couple rented a second-floor room on Arch Street from landlady Hannah Lithgow and ran their upholstery business from the ground floor.

Although committed to one another, the couple was not immune to the cauldron bubbling outside their door. Weary of King George III treating his overseas empire as his personal piggybank, the Colonists prepared for rebellion. The Patriots-one of whom was John Ross- formed the minutemen. In defiance of the tenet of her Quaker religion that advocated pacificism, Betsy sewed thousands of canvas cartridges that held gunpowder for muskets.

In 1776, John, while guarding a stash of munition, suffered injuries from an explosion of gun powder. His death left Betsy a twenty-four-year-old widow in the middle of the Revolutionary War, cut off from her family, friends, and faith. What helped her financially was the war proved profitable as there was a huge demand for uniforms and blankets. However, it was another product that made Betsy Ross an integral thread in the tapestry of Americana.

In 1776, each unit of the revolutionary army flew its own flag, most which embodied red, white, and blue, the colors of the British Union Jack. Colonists clamored for a standardized design to represent the fledgling United States.

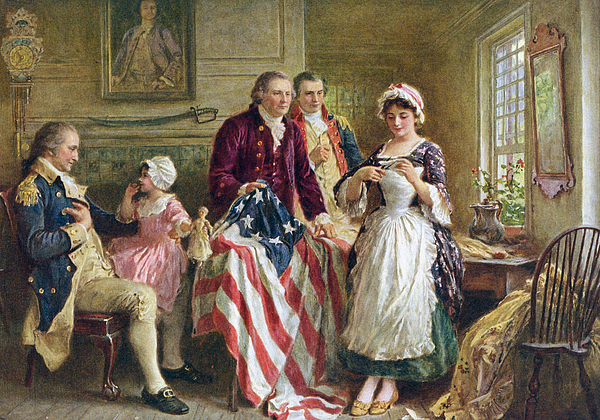

Lore holds that General George Washington, John Ross, and Robert Morris, in Philadelphia to attend the First Continental Congress, visited the Arch Street upholstery shop to commission a new flag. John had chosen Betsy as she was the widow of his nephew; George favored her as he was pleased with the bed hangings, pillows, and mattresses she had provided for his Mount Vernon estate. Their sketch showed a model with thirteen red and white stripes with a blue square in the upper left-hand corner bearing thirteen stars in a circle. Betsy suggested that the six-pointed stars be changed to five since that pattern was easier to make. The following year, on June 14, 1777, Congress passed a law that the United States had proclaimed the flag be “white on a blue field, representing a new constellation.” Although no proof exists that Betsy was behind the historic enterprise does not mean it was not true. As it was treason to produce any flag other than the Union Jack subterfuge would have necessitated keeping their plan under wraps.

Amidst running her store, producing munitions for the army, and sewing slings for the wounded soldiers, Betsy found romance with sailor-soldier Joseph Ashburn who she wed at Philadelphia’s the Old Swedes’ Church. The new wife sewed a flag for Joseph’s ship, the Hetty. The Ashburn’s baby, Aucilla, died before her first birthday; three years later, their second daughter, Eliza, was born. Once again, the war summoned her spouse and Joseph set sail on the Lion, bound for Europe on a mission to destroy enemy ships. John ended up in the British Old Mill prison, where he succumbed to disease brought on by overcrowding and unsanitary conditions.

When the war ended, Betsy was once again a widow. John Claypoole, someone she had known from her childhood, who had also been a prisoner in the Old Mill, delivered the devastating news. Two years later, Betsy took her third trip down the aisle. The Claypooles became members of the Free Quakers, a branch of the religion whose views were less extreme. Eliza became the big sister to the Claypoole’s four daughters. Their last baby, Harriet, died at ten months. Their upholstery business flourished, and the Claypooles were able to afford a house, a horse and carriage, and private schools. John was also active in the abolitionist movement. The Yellow Fever bypassed their family, although it claimed the lives of Betsy’s parents and sister Deborah.

In 1800, John suffered from a stroke and remained bed-ridden for the rest of his life. The business faltered and they depended on charity from the Free Quakers. John passed away seventeen years later; Elizabeth Griscom Ross Ashburn Claypoole died at age eighty-four, one of the few females to feature in the Founding Father saga.

Eventually, the story of the first flag-maker became so popular Betsy’s house became a tourist mecca. The Munds, a German immigrant family, hung a sign out front that read, “First Flag of the US Made in This House.” In 1898, Philadelphia formally established the building as the American Flag House that eventually transformed to the Betsy Ross House. From a flagpole hangs the Stars and Stripes with a circular star pattern, and a plaque bears the inscription, “She produced flags for the government for over 50 years. As a skilled artisan Ross represents the many women who supported their families during the Revolution and early Republic.” More than 250,000 visit the house each year, a historic home located a few blocks from Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell.

In 1971, twenty-five anti-war demonstrators barricaded themselves in the Betsy Ross House to protest the Vietnam War. The activists released fifteen tourists from the souvenir shop and then proceeded to hang the flag upside down. Three years later, the museum transferred the remains of Betsy and her third husband from the Mount Moriah Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania, to the garden located in the courtyard. On July 4, 1961, a thief made off with the flag that continuously flies over the legendary lady’s grave. The museum immediately found a replacement.

A docent, dressed as Betsy, leads tours of the house where visitors can experience an eighteenth-century upholstery shop, and view six rooms furnished with period pieces and antiques. The guide points out the parlor where Betsy met with George Washington, her bedroom where she secretly sewed the rebel flag, and the basement where she produced contraband for the Continental Army. The House’s personal effects are Betsy’s walnut chest, Chippendale chair, eyeglasses, snuff box, and family bible.

Even if Betsy’s role in the creation of the first American flag is not historically substantiated, there is enough information to prove she is far more than a Paul Bunyan or a Johnny Appleseed. She was a remarkable eighteenth-century woman who withstood excommunication from her family and church, the loss of three husbands, and life in the epicenter of the American Revolution. The ancient Greeks’ glory was their myths; a contemporary equivalent is Betsy Ross, America’s own Minerva.

THE VEW FROM HER WINDOW:

The woman memorialized on a 1952, three cent stamp, during the Revolutionary War years was privy to Philadelphians who were hungry-due to the British blockade- and who were reduced to burning furniture to keep warm.

NEARBY ATTRACTION: ROCKY STATUE

To the right of the Philadelphia Museum of Art stairs-the ones that the celluloid boxer climbed in the movie to the soundtrack of “Gonna Fly Now,” is the 8-foot-6 inch sculpture of Rocky, the irresistable selfie-magnet.