It Was, It Was

“I am happy that what was once so much pleasure for me turns out now to be a pleasure for other people.” – Alice Austen, speaking of her photography

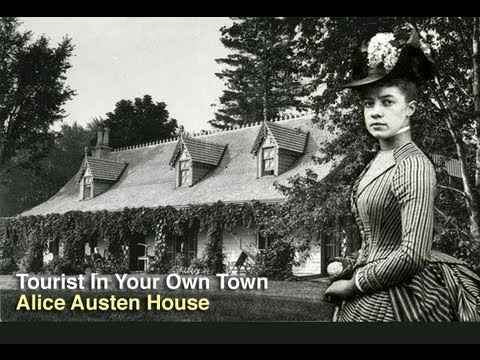

The Alice Austen House (opened in 1985)

2 Hylan Boulevard, Staten Island, New York

Simon and Garfunkel, folksingers from Queens, crooned in Bookends, “I have a photograph. Preserve your memories. They’re all that’s left you.” Alice Austen proved the veracity of their words. As the Klondike Gold Rush began in Alaska, Alice mined black and white nuggets in New York. The Alice Austen House has a dual distinction: it is the only American museum dedicated to a female photographer; the first designated as a LGBT Historic Site.

In 1866, during a baptism at St. John’s Church in Staten Island, Alice Cornell Austen christened her baby Elizabeth Alice Munn. The child preferred her middle name and rejected her last one as her father, Edward Stopford Munn, had taken off during his wife’s pregnancy. Without means of support, Alice moved into her parent’s home that was also the residence of her brother, Peter, sister, Mary, “Minn” and her brother-in-law, Oswald Müller. Alice grew up in the aptly christened Clear Comfort in the Rosebank neighborhood of Staten Island. At the time, the borough was transforming to the Newport of New York as mansions and yacht clubs dotted its shoreline. The residence dated from the seventeenth century, and her seafaring grandfather, John Hagerty Austen, had purchased it in 1844. After extensive renovation, the Victorian Gothic style house with its gingerbread trim and dormer windows held elegant furnishings and interesting curios two servants kept dusted. The third domestic was their cook. The lawn held a huge sycamore tree, and flowers carpeted the yard. Clear Comfort afforded a panoramic view of New York Harbor, and the twenty-year-old Alice witnessed the unveiling and construction of the Statue of Liberty until the landmark achieved her final height of 151 feet.

As the only child in a household of adults, Alice was the axis upon which her family revolved. She used the expression “larky” to describe a life filled with affection, security, and love. Her most precious possession was a camera-that resembled a wood box- that Oswald, a Danish sea captain, had given her when she was ten years old. Peter, a chemistry professor at Rutgers, showed her the alchemy of developing pictures. The two men converted a second-floor closet into a darkroom for their niece. A maid assisted with the task of rinsing glass plate negatives in the outdoor pump as the nineteenth century structure had no running water. Enamored of her hobby that transformed everything into a frozen snow globe of memory, Alice made Clear Comfort, her relatives, Punch, her pug, and Chico, her Chihuahua, the objects of her photos. The siren call of the harbor was also an early muse, and time after time, she raised her lens to ships, first powered by sail, then by steam.

A woman who dressed in the latest fashion, Alice’s activities included the new sport of tennis, gardening, sailing, and travelling. A horse-drawn carriage was at her disposal to transport her to skating parties and car races. Among Alice’s accomplishments: the first woman on Staten Island to own an automobile, a pioneer of the women’s bicycling movement, founder of the Staten Island Garden Club. But the lion’s share of her time was spent in the pursuit of photography. Just as the British Miss Austen chronicled the Regency era with her quill, the American Miss Austen captured nineteenth century New York with her photographs. What made Alice stand out-other than being the woman who wielded a camera at a time only the provenance of males- she pursued action shots rather than staged studio portraits. Her camera made its appearance on sailboat outings, and she shot scenes from moving trains. A social historian, Alice snapped images of her upper middle-class milieu and of scenic spots such as the swan boats bobbing on the Central Park pond. Intrigued by the financially disadvantaged, weighed down with fifty pounds of equipment strapped to her bicycle, Alice zoomed in on the denizens of the Lower East Side: fishmongers, organ grinders, child laborers, and chimney sweeps. For several years, the shutterbug visited quarantine stations where immigrants waited to be processed at Ellis Island. Other subjects that piqued her passion were horse-drawn carriages travelling along roads in proximity to early motor cars. The glass-photographic negatives bore her initials: EAA. Her work demonstrated technical prowess and she documented the time and date of each shot in her portfolio entitled “Street Types of New York.”

Life became ever “larkier” in the final months of the nineteenth century on a vacation spent at the Twilight Park resort in the Catskills when the thirty-one-year-old Alice met the twenty-six-year-old Brooklyn-born Gertrude Amelia Tate. Due to the Tate family who declared the women’s relationship a “wrong devotion,” Gertrude only moved into Clear Comfort in 1917. In contrast, the only closet Alice entered was her darkroom. Her unabashed attitude took courage; across the pond, Britain had incarcerated Oscar Wilde for acts of “gross indecency”- homosexuality.

Another treasure trove of photos would have scandalized the staid Victorian society. “The Darned Club,” shows two female couples, their arms wrapped around each other’s waists. In another, three women are dressed in male attire and phony moustaches; Alice’s friend, Julia Martin, is seated with an umbrella protruding between her legs, suggestive of an erect male member. A further snapshot showcases ladies clad in underwear, hair down, smoking in a church rectory.

The “larkiness” ended when the Stock Market Crash of 1929 wiped out the money Alice had inherited from her grandfather. During the Depression, Gertrude’s income as a dance teacher dried out. The couple tried to bolster their flagging finances by running the Clear Comfort Tea Room where a specialty was a lobster-salad adapted from the famed eatery, Delmonico’s. Despite the spectacular view and high-class cuisine, The New Yorker wrote, “It’s about what you’d expect if your oldest aunt, (the one who was considered artistic rather than domestic), had started up such a business without doing a great deal about it.” In desperation, Alice borrowed against the house, and sold the Austen heirlooms and furniture to antique dealers. A further effort to stave off debts was by renting her late Uncle Oswald and Aunt Minn’s room to Dr. Richard Cannon and his wife, Mary. In 1945, the court ordered Alice’s eviction for failing to make her mortgage payment. Gertrude’s sister allowed her to move in with her but did not extend the invitation to her lesbian lover. As her family members were deceased, suffering from arthritis and dependent on a wheelchair, the former society matron ended up in the municipal poorhouse at the Staten Island Farm Colony. A naked lightbulb hung over her cot.

Yet, fortune had not entirely abandoned Alice. Before her forcible removal from Clear Comfort, Alice had safe-guarded thousands of her glass-plate negatives. Oliver Jensen, an editor at American Heritage magazine, discovered them in the Staten Island Historical Society while doing research for his book, The Revolt of American Women. The forgotten cache of photos led to a 1951 exhibition and the publication of her work in Life magazine. During the ceremony in honor of the Grand Dame of photography, Gertrude basked in her lover’s glory. The exposure led to donations that allowed Alice to move into a private nursing home where she died a few months later at age eighty-six. The Historical Society financed her burial in the Austen family plot in the Moravian Cemetery at New Dorp in her native borough. A decade later, Gertrude passed away. Despite their wishes, the Tate family did not allow the long-term lovers adjoining burial plots. Gertrude’s internment was at the Cypress Hill Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Staten Island was far more fun when Alice and Gertrude were alive, and the best way to reincarnate their vivacious spirits is to take the Staten Island ferry to the Alice Austen House. The property is under the auspices of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation and is operated by the Friends of Alice Austen House that welcomes 8,000 annual guests. Victorian-era photographs adorn the house’s patterned wallpaper that summon the ghosts of the ladies of yesteryear who engaged in erotic same sex tableaus and dared to exchange their corsets for trousers. A remnant of Alice’s reversal of fortune is a gold brocade-covered armchair that she sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1933 in a desperate bid to buy more time in Clear Comfort. The chair is still their property, but the Alice Austen House rents it from the Met. The film, Alice’s World, narrated by Helen Hayes, plays continuously on video. While Gertrude and Alice’s Parisienne home served as the shrine for modern art, the other Gertrude and Alice’s Staten Island home is an altar of photography. And, standing on Clear Comfort’s porch overlooking her water-front property, the waves carry the cadence of Bookends, “What a time it was, it was….”

The View from Her Window

Alice adored Clear Comfort, and one of her favorite spots was the covered porch that provided her sweeping views of lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. Waves lap the pebbled beach, while the white picket fence serves as sentry from an intrusive, outside world. Nestled on a Staten Island Beach-once the private preserve of the Austen family, it offers the most panoramic view of all five New York boroughs.