Messenger Boy (1844)

Popular belief holds that Jack Dorsey was the founding father of social media when he created Twitter in 2006. However, instant long-distance communication began two centuries earlier when Samuel Morse instituted history’s most famous code.

In the Little House on the Prairie days, people sent letters that travelled with the speed of stagecoach and ship. Ironically, the invention that helped snail mail go the way of the dodo began with a letter.

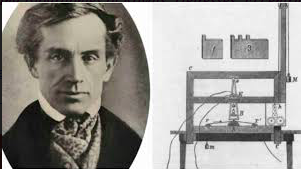

The man who invented instant messages was Samuel Finley Breese Morse, born in 1791, the eldest son of Josiah Morse, minister of a Congregationalist church in Massachusetts. His father rued he was “an easily distracted child.” Although Morse studied science at Yale, he travelled to Europe to pursue his passion for painting. Bitterly disappointed that his oversized canvasses earned praise but few sales, in 1832 he returned home aboard the Sully. From a deck side conversation, he had his eureka moment: electromagnetism could travel along wires that would result in sending information within moments rather than months.

Upon his return, in order to support his wife Lucretia and two children, Morse became a portrait painter; his most esteemed commissions were of the Marquis de Lafayette, Eli. Whitney, and President James Monroe. Nevertheless, still dogged by money problems, Morse felt he was a failure. At low ebb, in 1835, Morse received a letter from his father in New Haven, Connecticut, that shared Lucretia had taken ill after the birth of their third son. Immediately Morse set off for home; because of the time it had taken for the horse-drawn letter to arrive, Morse had missed his wife’s final moments as well as her funeral. The widower wrote, “My whole soul was wrapped up on her…she connected all that I expected of happiness on earth.”

The snail pace of mail reminded Morse of his Sully revelation, and he devised a series of dots and dashes that would be the language of the telegraph, so named after "to write at a distance." After demonstrating his new technology in a building, Congress awarded him $30,000.

At age fifty-three, Morse arranged for a wire to run from Washington, D. C. to Baltimore, Maryland, wherein he tapped out dots and dashes to his colleague, Alfred Vail, the Old Testament quotation from Numbers 23:23, “What hath God wrought?” The literal answer appeared days later when news travelled by telegraph of James K. Polk’s winning the Democratic presidential nomination in Baltimore. The age of the telegraph ended the reign of the Pony Express, and ushered in the era of the telephone, the Internet, the smartphone.

The possessor of fame and fortune, Morse bought Locust Grove, an Italian villa mansion overlooking the Hudson River, and lived to see telegraph wires connecting the world from America, Europe, Asia, and crossing the Atlantic by underground cable. The new technology gave birth to Western Union and The Associated Press, and the Morse code international distress symbol-SOS-became ubiquitous. Upon Morse’s 1872 death, telegraph operators draped their instruments in black. One accolade Morse never lived to see was the 1982 sale of his painting, “The Gallery of the Louvre,” for $3.35 million.

The telegram made notable appearances: in 1912, “SOS SOS. WE ARE SINKING FAST. TITANIC.” In 1917, the decoding of the Zimmermann telegram instigated the Unites States’ entry into World War I. The briefest telegram was from Oscar Wilde in Paris, “?” to his publisher in Britain, regarding the sales of his books. The exuberant response, “!”

The telegram that most aligns with the spirit of Morse was evangelist’s Billy Graham’s words, “I am only a Western Union messenger boy, delivering a telegram from God.”