La Dame aux Camélias

“We are the breakers of our own hearts.”

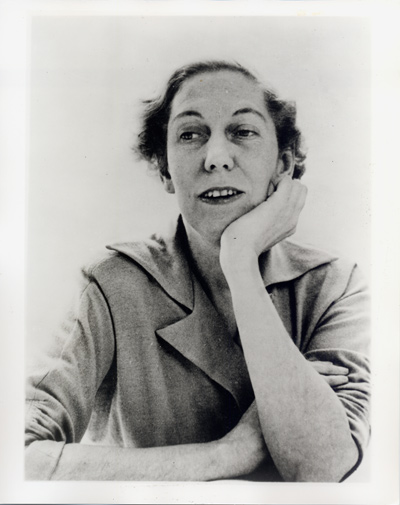

–Eudora Welty

Eudora Welty House & Garden (opened 2006)

Jackson, Mississippi

Although her home was where Eudora Alice Welty did her writing, it never went by a literary name, as did Virginia Woolf’s Monk’s House, Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House, or Jane Austen’s Chawton House. Eudora referred to her residence as, “Tudor style with some timbering, you know, à la Shakespeare.” To learn about the literary landmark, set your compass to the Eudora Welty House & Garden.

Along with contemporary writers such as Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, and Tennessee Williams, Eudora shaped the Southern Literary Renaissance. Eudora was the daughter of Methodist parents, Christian Webb Welty, a successful insurance executive, and Chestina Welty, a teacher before marriage. The couple was thrilled with the birth of their son, Christian. When the baby was fifteen months old, he and his mother became ill. Chestina suffered from septicemia that resulted in the loss of her long hair. Her husband placed the locks in a bag in a bureau drawer. Chestina survived; her son did not. Before his burial, his grieving mother removed the two polished buffalo nickels that had covered his eyes. She placed them in a cardboard box. Joy followed loss with the 1909 arrival of Eudora.

In addition to a childhood enveloped in love, Eudora grew up with a milieu of books. Eudora recalled the exhilaration when she first fell under the spell of the written word, “It had been startling and disappointing to me to find out that storybooks had been written by people, that books were not natural wonders.” A ritual, what she referred to as “a sweet devouring,” was checking out books at the Jackson Public Library. Two things irked Eudora: the librarian, Mrs. Calloway, only allowed patrons to check out two books at a time, and they could not be returned the same day. Several decades later, the library bore the name of Eudora Welty. On Sundays, her father took her to his office where she was allowed to use his typewriter. She recalled, “It used to be wonderful to be in Daddy’s office. That’s where I fell in love with the typewriter.” Christian and Chestina instilled the values of The New Testament in their children-that grew to include sons Edward Jefferson and Walter Andrews.

One day, Eudora discovered a cardboard box on her mother’s bureau and removed the strands of russet-colored locks that reminded her of Rapunzel, a favorite fairy tale. In another box she found two buffalo head nickels, and asked her mother if she could spend the coins. Chestina explained her refusal by telling her about the baby brother who had died before she was born. The episode made a lasting impression on Eudora that would later infuse her stories: objects carried messages of love, loss, and the power of the past on the present.

Eudora attended the Mississippi State College for Women in Columbus, Mississippi–the first state college in the country to admit females–that mandated students attend chapel. An extra-curricular activity was starting a literary magazine. She ended up obtaining her bachelor’s degree in English at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wisconsin. Hell-bent on making her livelihood as a writer, she nevertheless took her father’s advice to pursue a practical career. She enrolled in an advertising/secretarial program at the Columbia University School of Business in New York, a field that did not speak to her soul. Mrs. Welty, an avid gardener, sent Eudora boxes of camellias by train to Manhattan. Eventually, New York exerted a magnetic pull, and Eudora decided to remain after graduation. Fate had other plans. She hurried back to Jackson when she heard her father was dying of leukemia. In the hospital, Eudora watched as her mother lay on a cot beside her husband, a tube ran from her arm to his as the doctors performed a blood transfusion. Christian passed away in September of 1931.

Eudora turned to writing to chronicle her truth, “My continuing passion was not to point the finger in judgment but to part a curtain, that invisible shadow that falls between people.” In 1936, a magazine named Manuscript published her first short story, “Death of a Traveling Salesman” that recounted the last day of a lonely man taken in by two hillbillies in rural Mississippi. The year 1941 marked the release of a compilation of her short stories with an introduction by Katherine Anne Porter, author of Ship of Fools. Eudora’s fictional world revolved around the historic forces that shaped the South. The landscape of her birth dictated that yesterday shadowed the present. She had remarked that General Sherman had burned Jackson three times.

In 1936, Eudora obtained a position at President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration that entailed travel throughout the Deep South. Distraught by the abject poverty, she took photographs that she developed in her kitchen. The un-staged shots captured unemployed men slumped on park benches. Random House published her pictures as One Time, One Place: Mississippi in the Depression.

Gravitating to fellow writers, Eudora befriended Katherine Anne Porter, Elizabeth Bowen, and Robert Penn Warren. An enduring bond was with her literary agent, Diarmuid Russell. An adherent of Southern hospitality, Eudora rarely turned down interviewers who enjoyed bourbon and a home-cooked meal. However, when Henry Miller–with who she shared a publisher–arrived in Jackson, Chestina refused to let him visit as she had heard that he wrote pornography. For the duration of his stay, Eudora drove him around in her family’s Chevrolet, where she brought along chaperones in case he acted like one of his sex fiends in The Tropic of Capricorn. Eudora pronounced Henry the dullest man she had ever met, and who “wasn’t interested in anything outside himself.” (In contrast, Eudora deeply disliked when the conversation revolved around her). As much as she did not care for Henry, she revered William Faulkner and was ecstatic when she received his letter where he complimented her writing, “You’re doing all right.” Ecstatic at receiving a letter from Faulkner, Eudora sent it a friend in Oxford. Later, the “friend” sold the letter to the University of Virginia for a “horrendous sum.” The University sent Eudora a carbon copy. Another treasured letter was from writer E. M. Forster that she framed and hung in an upstairs room, and later relocated to the ground-floor sitting room. Eudora shunned public accolades as evidenced in 1990. At the podium of the Folger Theatre in Washington, D.C., when 220 fans and authors erupted into a thunderous applause, she said, “Never happened to me before. I’m used to being last on the program because my name begins with a W.”

During World War II, Eudora worked for The New York Times Book Review contributing articles under the pseudonym Michael Ravenna, as the public felt ladies were not capable of serious commentary. She returned home to nurse her mother who had lost her husband and younger son, Walter. A source of solace was her garden that Eudora had embellished with an ornamental bench. In 1966, Eudora lost first her mother, and a few days later, her brother, Edward, who died from injuries sustained in a fall.

In 1973, Eudora received a phone call from Frank Hains at the Daily News who asked her “How does it feel?” she was perplexed until she glanced out her window where she saw two men approaching. Eudora had won the Pulitzer Prize for The Optimist’s Daughter.

Though fortunate in her choice of friends, she was less lucky in the romantic arena. She had a decade long friendship and relationship with John Robinson. He cared for her but often sent her mixed messages. The fly in the romantic ointment was when she discovered he was living with another man in Italy.

Another romance also came with a rub. In 1973, the Mississippi Arts Festival declared a Eudora Welty Day and asked the author to provide a guest list for her out-of-town friends. An acceptance arrived from author Kenneth Millar who wrote under the pseudonym of Ross MacDonald. The two met after the deaths of Eudora’s mother and brother, and Kenneth’s loss of his only child, Linda. In 1971, Eudora was staying at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City, and Kenneth had an adjoining room. He took Eudora to a cocktail party his publisher, Alfred Knopf, threw in his honor. When he left, Kenneth sent Eudora a postcard that had a photograph of the Kissing Bridge in West Montrose, Ontario. On the other side was the message, “Treasuring fond memories of New York and you.” As with the television show Friends, where for years viewers wondered will they or won’t they–the same situation applied to the Southern writer and the crime fiction detective. The answer is ambiguous which is something the couple, who both enjoyed mysteries, would have approved. Despite their love, Ken never divorced his wife, Margaret. By 1980, Kenneth developed Alzheimer’s disease; Eudora wrote to him, “You’re dear in every way to me, and I think of you in such concern and love.” After his 1983 passing, Eudora attempted to write a story about him, her, and Margaret, but she admitted it was a tale she “could not and would not finish.” Whether their love extended to a physical plane is lost in the miasma of the Southern night, but passion there was. Kenneth told Reynolds Price, “You love Eudora as a friend. I love her as a woman.” When asked about her single status, Eudora’s response, “Marriage never came up.” Even the buffalo nickels did not hint at tangled life could be.

As much as Eudora preferred escaping the public’s radar, irate Northerners called in the middle of the night berating her for refusing to write about her region’s rampant racism. Her counter was authors were not required to preach from a political pulpit. However, when she felt strongly about an injustice, she used her pen to puncture the poison. When Byron De La Beckwith shot Medgar Evers, the black, civil rights leader, in Jackson, on the night of the assassination, she began her story, “Where is the Voice Coming From?” that explored the mind of a bigoted psychopath. She sent it to William Maxwell, the editor at The New Yorker. With the arrest of Beckwith, to avoid a libel suit, Eudora and the editors changed some details. Post publication, a journalist called Eudora and asked if anyone had burned a cross on her lawn. Her rejoinder, “The people who burn crosses on lawns don’t read me in The New Yorker.”

In recognition of her contribution to literature, accolades poured in. In 1962, Eudora presented fellow Mississippi writer, William Faulkner, with the Gold Medal for Fiction. Another Mississippi recipient was Tennessee Williams, who won it for drama. Her friend, Katherine Anne Porter, shared the same honor. In 1972, President Nixon appointed Eudora to the National Council for the Arts. Eight years later, President Jimmy Carter–who she referred to as “one of my great Southern heroes–awarded the grande dame of American letters the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The accompanying accolade stated that her fiction “illuminates the human condition” while her essays “explore mind and heart, literary and oral tradition.” Ms. Welty collected awards as Imelda Marcos collected shoes: honorary ones arrived from Harvard and Yale. She was also the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize and France’s Légion d’honneur.

Eudora Welty House & Garden: Eudora observed, “A place that was ever lived in is like a fire that never goes out.” Her words show why she had fealty to the Tudor-style home where she had lived from age sixteen until her death at age ninety-two. In 1986, the author deeded her residence to the Eudora Welty Foundation, thus saving the organization from having to restore the structure to its historic condition. The Foundation’s brochure refers to the residence as “one of the nation’s most intact literary house museums.” While many writers’ residences’ have a stuffy atmosphere, replete with ropes and hospital corner sheets on beds, the Welty home seems as if she had just stepped out to the Mayflower Café for a plate of fried catfish and butter beans.

In every room books are found on shelves, on her walnut dining room table, stairs, and couches. A charred set of Charles Dickens’ novels carried a history: they had been a gift from Chestina’s father, and she had once rushed back into her burning home to rescue them from the flames. Bric-a-brac abounds such as a gaudy bust of Shakespeare on the mantel. Self-effacing, Eudora kept her many awards in a cardboard box in an upstairs closet. Currently, they are in the house next door that serves as the Visitor Center. Also on display are various literary awards including her Pulitzer Prize. Guests might experience a sense of déjà vu as some of the objects made their way into her work such as the desk from The Optimist’s Daughter that is in her second-floor bedroom, one that was off bounds to visitors. At her desk, situated near a window, the author tapped away on her typewriter. (hose touring the home are permitted to try tapping some keys in the next-door visitor center; it is not an original model). On her bureau rests perfume bottles, a jewelry box, and a comb. A wooden plaque reads: Eudora’s Room.

The museum holds items that were near and dear to the author’s heart; for example, her adored father’s gold pocket watch and telescope, a favorite book from her childhood, the typewriter she took to Europe, and a RCA Victor album. An exhibit showcases photographs and news items of Medgar Evers that details how his assassination helped fuel the Civil Rights Movement. The case displays a vintage watering can, tools, photos, and flower related objects.

If the house was Eudora’s heart, her garden was her soul. When her night-blooming cereus yielded a flower, to partake of its beauty, Eudora threw a party that lasted from dusk to dawn. The Mississippi Department of Archives ahd History undertook the restoration of the gardens. Thev recreated Chessie’s trellises, and arbors so visitors can enjoy what brought mother and daughter both joy and solace.

Eudora’s attachment to her home can be understood with her words, “One place understood helps us understand all places.” The Eudora Welty House & Garden provides insight into the South’s own La Dame aux Camélias.

The Window of Her World: From her window, Eudora saw the oak tree her mother had planted. From the opposite side of the street was Belhaven College. Wafted on the southern breeze, music from the college students blended with the clack of Eudora’s typewriter.