Girdled the Globe (1864)

“I have never written a word that did not come from my heart. I never shall.”

Some women can fit into one of the following categories: world traveler, fourteen siblings, married a millionaire, spent time in a madhouse, owned a pet monkey. However, in all likelihood, only the nineteenth century version of Brenda Starr dipped her toes in all of these waters.

The lady who beat a literary character at his own game was Elizabeth Jane, nicknamed Pinky by her mother, Mary Jane. Her hometown, Cochran Mills, Pennsylvania, had been founded by her father, Judge Michael Cochran, who had risen from mill worker to mill owner to judge. He had brought to his second family ten children from his first marriage, his second wife gave birth to five more. Tragedy struck when Michael passed away when Elizabeth was six and Mary Jane remarried, then divorced, an abusive drunk. Anxious to better her station, Elizabeth enrolled in the State Normal School with the aspiration of becoming a teacher. Unable to afford the tuition, she dropped out and helped her mother run a boarding house in Pittsburgh.

In 1885, Elizabeth read a column in The Pittsburgh Dispatch, by Erasmus Wilson, that bore the title: “What Are Women Good For?” According to the post, the answer was not much, other than “to be a helpmeet to a man.” Erasmus described working women as a “monstrosity.” Infuriated, Elizabeth wrote a scathing rebuttal and signed her letter, “Poor Little Orphan Girl.” The newspaper’s editor, George A. Madden, taken with the writer’s spunk, ran an ad asking the Little Orphan Girl to reveal her identity. When Elizabeth came forward, he asked her to write a column that she entitled “The Girl Puzzle,” that called for reform in the divorce laws that were skewered against wives. Madden offered her a full-time position at $5.00 a week. Casting about for a nom de plume, (she had previously added an ‘e’ to Cochran,) Madden turned for inspiration to Pittsburgh born Stephen Foster who had penned “My Old Kentucky Home,” the anthem of the Kentucky Derby. The editor landed on another Foster song “Nelly Bly,” though her editor misspelt it as Nellie, thus establishing her byline.

Elizabeth began her journalistic career by going under cover in sweatshops, reporting on the wretched conditions of their female workers. Infuriated factory owners threatened to withdraw their advertisements; consequently, the newspaper only allowed Elizabeth to write articles that fell into the category later known as “the pink ghetto,” focusing on topics such as flower shows and fashion. Miserable, she wheedled her bosses into making her a foreign correspondent, and she left for Mexico. For several months, she travelled throughout the country, reporting on corruption and the lives of the poor. Her articles ran afoul of the government and fearing arrest, she returned to the States. Her experiences were chronicled in a book Six Months in Mexico. After she was once again assigned to write on entertaining and childcare, she quit in protest. Her last act before departing The Pittsburgh Dispatch was to leave a note on Erasmus’ desk, “I’m off to New York. Look out for me. -Bly.”

In New York, Elizabeth finagled a meeting with Joseph Pulitzer, owner of The New York World. Pulitzer agreed to employ her if she infiltrated the Women’s Lunatic Asylum, located on Blackwell’s Island, (currently Roosevelt Island.) The famed newspaper tycoon offered no assistance on how to gain entry or how to leave once committed. In 1887, the activist became actress into order to appear a madwoman. Cochrane checked into a boarding house in the working-class Bowery District under the name Nellie Brown. Her pretense was she was from Cuba, ranted that she was searching for missing trunks, screamed, (an act aided by rats scurrying across her pillow,) and demanded a pistol. Her guise of insanity was so convincing that her roommate refused to sleep in the same room with her “for all the money of the Vanderbilts.” Doctors declared her, “Positively demented” and a few days later, she was aboard a ferry where she observed, “two coarse, massive female attendants who expectorated tobacco juice about on the floor in a manner more skillful than charming.”

In Blackwell’s Island, Elizabeth joined sixteen hundred other unfortunates where she experienced the inhumane treatments that included filthy garments, rancid food, and sadistic caregivers. Complaints resulted in beatings with a broom. Elizabeth questioned, “What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?” Baths consisted of three buckets of freezing water poured over her head that gave the sensation of drowning. Dripping wet, nurse Ratchetts forced her into a short cotton flannel slip that bore the words: Lunatic Asylum, B. I. H. 6” for Blackwell’s Island, Hall 6. When Elizabeth asked for a proper nightgown, an attendant sneered, “We have no such things here. You are in a public institution. Don’t expect anything or any kindness here for you won’t get it.” The twenty-three-year-old reporter lived among those who were suicidal, psychotic, as well as perfectly sane women who had been committed by husbands who wanted them out of the way. One inmate’s heavily accented German was mistaken for gibberish that had led to a diagnosis of madness. Even when Elizabeth dropped her act and appeared intelligent and coherent, no attention was paid. Exhausted and starving, Elizabeth was overjoyed when, ten days later, lawyers from The New York World arranged for her release. Two days later, the newspaper published Cochrane’s exposé as Ten Days in a Madhouse that likened the asylum to a human rat trap, under the headline: “Inside the Madhouse.” The article recounted how hospital administrators injected their patients with so much morphine that they were rendered comatose and incoherent. The account shocked the public so much that it led to an investigation. A month later, the city added a million dollars to the institution’s budget and arranged for an overhaul of the facility.

Bly became a journalistic Robin Hood exposing the rotten core of the Big Apple. Whenever there was an injustice directed against women, children or the poor, Nellie Bly was there. To investigate how females fared in New York City jails, she posed as a thief in order to experience incarceration. Her attempt failed when the police recognized her and gave her preferential treatment. On one occasion, she wrote about the black market, “I bought a baby last week, to learn how baby slaves are bought and sold in the city of New York. Think of it! An immortal soul bartered for $10! Fathers-mothers-ministers-missionaries, I bought an immortal soul last week for $10!”

Future assignments involved meeting the female power players of the day such as Susan B. Anthony, who Bly called the “champion of her sex,” and about Emma Goldman in which she portrayed the activist as a person rather than an anarchist. In an article ages ahead of her era, she asked the marital question: Should Women Propose? In her free time, Elizabeth dabbled in elephant training and took up ballet.

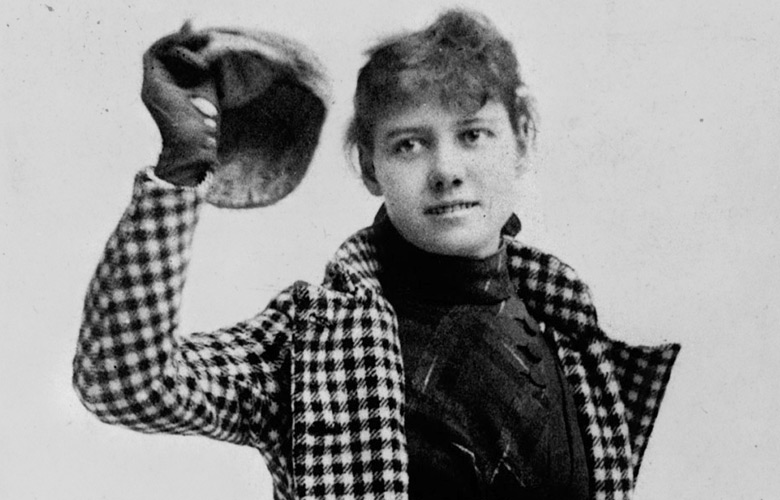

After her stint in a madhouse, what could a famous reporter do next? Elizabeth found her idea in the Jules Verne novel, Around the World in 80 Days and approached Pulitzer with the proposal that she could best Phineas Fogg’s record. Although impressed by the concept, Pulitzer told her that her gender would make the trip impossible. Cochrane’s response, “Very well. Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.” The New York World conceded. Cochrane added she would make the trip without a chaperone and with only one small satchel. Dressed in her distinctive black and white plaid Ulster coat and hat that resembled Sherlock Holmes’ deerstalker cap, Elizabeth boarded the steamship Augusta Victoria, bound for England.

In dispatches to The New York World, Elizabeth chronicled her experiences such as the casino in Egypt where she lost money at roulette, the snake charmer in Ceylon, the instruments of torture in China. Another stop was a visit to Verne and his wife, Honorine, at their home in Amiens, France. Committed to travelling light, her only souvenir was a monkey she named McGinty, purchased for $3.00 in Singapore. The New York World experienced a spike in sales as they covered her voyage. Trading cards and games bore her image while a hotel, a train, and a racehorse bore her name.

In a voyage that entailed rickshaw, horses, and donkeys, after seventy-two days, six hours, and eleven minutes, the triumphant Elizabeth returned, an international celebrity. Thousands of fans greeted her as she stepped off the train; ten celebratory gunshots boomed from Battery Park; boats in New York harbor sounded their whistles. A mountain of congratulatory telegrams awaited, including one from Verne. Cochrane reveled in her reputation that, as an admirer put it, established the American woman as “pushing, determined, and independent.” The young woman who embodied Scarlett O’Hara’s waist as well as her gumption became America’s most well-known woman. A book chronicled her adventures: Nellie Bly’s Book: Around the World in Seventy-two Days (1890). Because of her journalistic coup, Elizabeth expected a bonus and editorial recognition; but Pulitzer scarcely acknowledged her feat. Angered at the lack of appreciation and acknowledgement, Cochrane quit and embarked on a lecture tour where she earned $9,500, $250,000 in contemporary currency. In 1890, upon the death of her brother Charles, Elizabeth took over the care of her widowed sister-in-law and her two children.

At age thirty, Elizabeth married Robert Livingston Seaman, a millionaire forty years her senior. Fans and friends joked she was only trying wedlock for the story; however, she abandoned reporting to work with her husband in his steel-container business, the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company, that employed a work force of 1,500. Upon his death, she took over the factory and instituted numerous reforms, including health and recreation benefits. The business floundered, and Elizabeth was forced to declare bankruptcy. Once again experiencing the financial straits of her childhood, she returned to journalism with The World where her columns were dedicated to unearthing corruption. In 1913, Cochrane covered the Woman’s Suffrage Parade and published the report with the headline “Suffragettes Are Men’s Superiors.” The draw of World War I proved a powerful magnet, and she boarded the RMS Oceanic, bound for three weeks in Vienna; she became the first woman to reporting on the Eastern Front. The New York Evening Journal published Nellie Bly on the Firing Line, a column that carried her columns of the carnage. In the thick of the fighting, she fell under suspicion and ended up under arrest as a British spy. In her final years, as a reporter for the New York Journal, she took up the cause of abandoned, abused, and missing children and became a “fairy godmother” to an orphaned girl.

Elizabeth Cochrane, immortalized as Nellie Bly, passed away from pneumonia, and her internment took place in the Bronx. One would hope that her last thoughts, rather than have returned to the ten days in the madhouse, instead relieved her time of glory when she had, as written in The New York World, “girdled the globe.”