Failure is Impossible

Susan B. Anthony House (opened 1971)

Rochester, New York

“Men, their rights, and nothing more; women their rights, and nothing less.” Susan B. Anthony

The unwavering friendship between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Antony formed the foundation of the American suffrage movement. Elizabeth supplied the speeches that Susan delivered, “I forged the thunderbolts and Susan fired them!” For those desperately seeking Susan, one should make a pilgrimage to the Susan B. Anthony House.

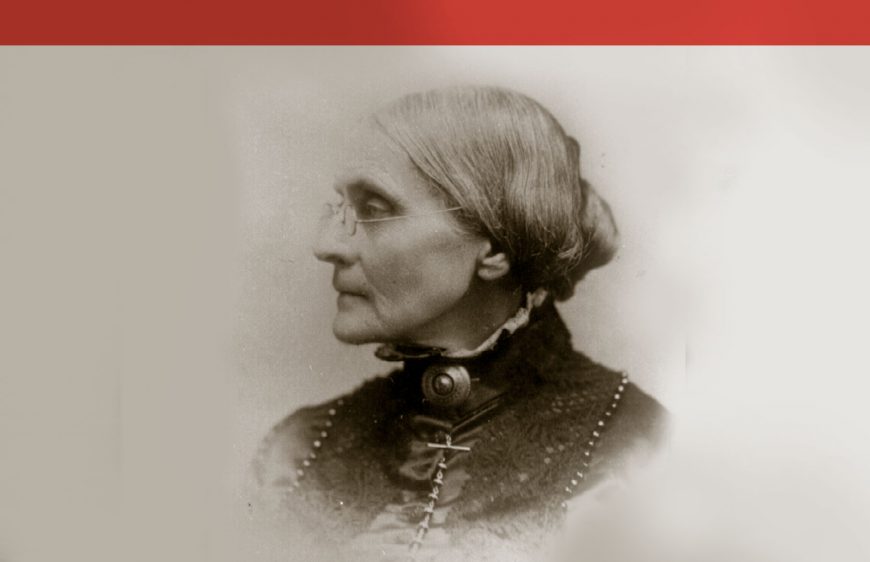

The Quaker faith, (so called as members were said to quake in the presence of the Lod,) was the bedrock of Susan’s soul and provided her with the courage to slay the hydra heads of injustice. Susan Brownell, (disliking her middle name, she only went by her initial,) was born in 1820, the second oldest of seven children of Daniel and Lucy Anthony. Along with her sisters Guelma, Hannah and Mary, Susan shared the same educational opportunities as her brothers. As a child, Lucy’s right eye became crossed with a tendency to wander that led to difficulty in reading and to be photographed in profile. The family lived in Adams, Massachusetts, until Susan was six, when they then moved to Battenville where Daniel opened a mill. Susan wondered why Sally Ann Hyatt, her father’s employee, although more knowledgeable than Elijah, her supervisor, was not in charge. Daniel’s response that a woman could not hold the reins did not sit well with his daughter.

The Panic of 1837 led to the loss of livelihood, and, to help with finances, Susan became a teacher, one of the few jobs open to women. What rankled her was the Quaker school’s female instructors earned one-quarter the salary as their male counterparts. Her next position was in New Rochelle, New York. She had no wish to follow Guelma into holy matrimony as she felt there were unholy things about the institution such as a woman could not seek a divorce, retain custody of her children, have a voice in money matters. Eventually, politics took precedence, and Susan focused her efforts on righting societal wrongs. While attending the convention of Sons of Temperance men told her to “listen and learn.” She ended up as the President of the local branch of the Daughters of the Temperance Movement. A rebel with many causes, Susan joined the American Anti-Slavery Society. Mobs pelted her with rotten eggs, hung her in effigy, and burned her image in the streets of Syracuse. A newspaper called her a “pestiferous fanatic.”

Taking New England somberness to the extreme, Susan was immune to anything other than her cause. Breakfast in bed led to feelings of guilt; the first time she stepped foot on a beach was at age sixty-seven. A decade later she experienced her first football game that she declared, “It’s ridiculous.” Likewise, she punctured a hole in the concept of maternal instinct. Her thoughts on Elizabeth’s pregnancies was to wonder, how, “for a moment’s pleasure to herself or her husband, she should thus increase the load of cares under which she already groans?” The mother of six, Elizabeth was pregnant when Susan made the remark. Susan’s comment to suffragette Antoinette Brown Blackwell, “Now, Nette, not another baby, is my peremptory command.”

In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention took place in Seneca Falls, New York, where its 200 attendees adopted the Declaration of Sentiments. They modeled the document on the Declaration of Independence with the modification, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal.” Although Susan had not attended the historic meeting, she had found her cause de célèbre.

The start of a beautiful friendship occurred on a street corner in Seneca Falls when Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan to Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The women had no idea that their friendship would last for fifty years, that together they would stand at the vanguard of a revolution. Susan’s motto for their movement, “Organize, agitate, educate must be our war cry.” The two complemented one another: Susan possessed the organizational skills while Elizabeth was adept on a philosophical plane.

The partnership produced a newspaper, The Revolution, that advocated for fair divorce laws, equal pay, and the right for females to wear pants. The New York Sunday Times responded that Elizabeth should tend to her “domestic duties” and Susan needed “a good husband and a pretty baby.” In 1869, the friends formed the National Women’s Suffrage Association that championed suffrage for women as well as social, political, and economic equality. Henry Stanton remarked to his wife, Elizabeth, “You stir up Susan, and she stirs up the world.”

Susan’s greatest stirring of the pot occurred in relation to her Holy Grail: the ballot box. Her contention was that “disenfranchisement was akin to degradation.” In 1872, nearly fifty years before the passage of the 19th Amendment that granted American women the right to vote, Susan, accompanied by Guelma, Mary, and Hannah, as well as several other suffragettes, entered a Rochester barber shop where they demanded to be registered. When the polling officials hesitated, Susan read the Constitutional passage that promised all persons were entitled to equal protection under the law. On election day, Susan cast her vote for Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant due to his pro-women stance. The following morning, the New York Times covered the watershed moment under the heading, “Minor Topics.” In a microcosm of the misogyny of the era, the article referred to the women as “a little band of nine ladies.”

Susan was in her parlor when Deputy United States Marshall E. J. Keeney informed her that she was under arrest. She suggested he put her in handcuffs, an offer he declined. In the streetcar on the way to jail, when the conductor asked for her fare, she replied, “I’m travelling at the expense of the government.” At her preliminary hearing, Justice Ward Hunt set bail at $500.00. Susan had no intention of paying the fine as prison would draw attention to her cause. To her chagrin, her lawyer put up the money because he could not stand to think of a lady languishing in prison.

Anthony supporters argued that it was the United States that was on trial rather than Susan B. Anthony. In contrast, the Rochester Union called her a “corruptionist.” The trial venue was the village of Canandaigua, New York, where one of the spectators was former president Millard Fillmore. Judge Hunt refused to let Susan argue in her defense with the explanation that women were not competent to testify. After the lawyer finished his argument, the judge took a paper from his pocket and read his decision-thereby proving the verdict had been a foregone conclusion. He directed the jury to find her guilty. Susan forever referred to the trial as “an outrage.”

Before he read her sentence, Judge Ward asked the defendant if she had anything to say. She let a moment of what she called “sublime silence” pass before she stated, “Yes, Your Honor, I have many things to say. My every right, constitutional, civil, political and judicial have been tramped upon. I have not only had no jury of my peers, but I have had no jury at all.” When informed she would have to pay a fine of $100, she responded, “I will never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty.” She concluded, “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.”

Ms. Anthony fought her crusade in the eighteenth-century, red brick Susan B. Anthony House that had been her residence for forty years and, when she was president, was the headquarters of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. At the top of the narrow stairs is the attic where she worked on the posthumously published History of Woman Suffrage and The Revolution. Some of the original artifacts: a Singer sewing machine, typewriter, spinning wheel, eyeglasses, and shawl. A unique addition is the Anthony family pew from the First Unitarian Church of Rochester. Another treasure, encased in glass, is Susan’s alligator purse that inspired a jump-rope tune, “Call for the doctor!- Call for the nurse!-Call for the lady with the alligator purse!” The tour offers many soul-stirring opportunities such as standing in the parlor, the site of Susan’s arrest. Susan’s bedroom displays-encased in glass-her iconic silk black dress, near the bed in which she died.

The museum’s gift-shop offers miscellaneous items related to the activist. One is a $250.00 faux alligator purse stamped with the Ms. Antony quote, “Every woman needs a purse of her own.”

The firebrand delivered her last public words on her eighty-sixth birthday. During the celebration, she paid tribute to those with whom she had battled injustice, “But with such women consecrating their lives, failure is impossible.”

THE VIEW FROM THE WINDOW:

On election days, if Susan could once more gaze through her window she would see women laying “I VOTED “stickers on her grave in the nearby Mt. Hope Cemetery.

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS: Susan B. Anthony Square Park

A short walk from the Anthony house is a bronze sculpture of two old friends, fellow activists Susan and Frederick Douglass, sitting at a table. The name of the bronze tableau: “Let’s Have Tea.”