Aurora (1837)

The Princess of Wales and the Empress of Austria, though they lived a century apart, led parallel lives: both were married off to Europe’s most eligible royals, dealt with formidable mothers-in-law, and rued that fairy tale weddings do not always equate to a happily ever after.

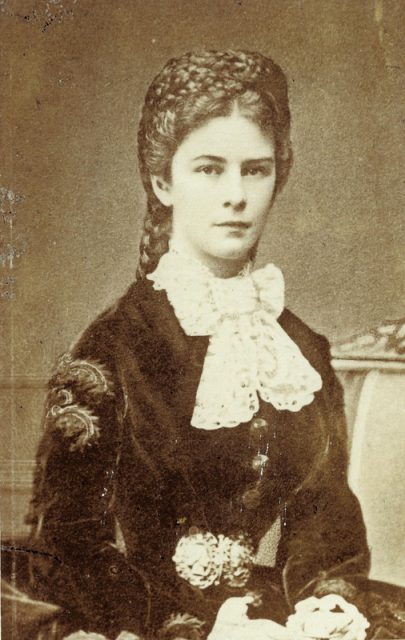

The girl who would become queen of a kingdom that had dominated the map for six centuries was one of the great beauties of her era, so much so that she captured the heart of an emperor. Elisabeth “Sisi” Amalie Eugenie arrived on Christmas Eve; each of the eight children-as well as two illegitimate daughters from her father-were so indulged that each year they received their own Christmas tree. Her enchanted childhood was spent at Possenhofen Castle on Lake Starnberg, outside Munich, where she and her siblings ran wild in the adjacent forest. Her mother, Ludovika, was the daughter of King Maximilian I; the patriarch was a duke from the House of Wittelsbach, the reigning dynasty since 1180. The ruler of the Bavarian kingdom was Sisi’s cousin, King Ludwig II, known as “Mad Ludwig.” His fairy tale mountain home, Neuschwanstein, later served as the model for Sleeping Beauty’s Castle in Disney theme parks.

Europe in the nineteenth century was the personal chessboard of the Habsburg dynasty whose members sat on almost every throne of the continent and wielded untold power. In 1853, Ludovika and her sister, Archduchess Sophie, arranged a match between their respective children. Ludovika brought the eighteen-year-old Helene, “Nene,” to the scenic resort town of Bad Ischl to meet the world’s most eligible bachelor, the newly crowned Emperor Franz Josef. However, when the king saw Sisi, who had tagged along for the trip, he was smitten: her chestnut hair cascaded to her ankles, her features seemed chiseled from a cameo, her waist smaller than that of Scarlett O’Hara. The Archduchess Sophie pointed out that Helene was his intended, and she was aghast when her dutiful “Franzi” declared the younger sister would be his bride. Reluctantly, the royal mother succumbed, at least comforted by the realization the teenager would instill an infusion of popularity into the stodgy regime. Sisi was flattered at being the love interest of one of the world’s most powerful men. Nevertheless, doubts about her new role nagged at her elation, “I love the Emperor. If only he were not the Emperor.”

At age sixteen, Sisi was the most envied of women when she became engaged to Europe’s most powerful and wealthy king. The royal wedding of 1854 caused a sensation as thousands had lined Vienna’s streets to catch a glimpse of the princess bride. In her glass coach, Sisi sobbed with trepidation. As it transpired, she became the people’s princess due to her sweet disposition, dedication to charitable causes, and ethereal beauty. Queen Victoria found the Empress “even lovelier than she had been led to expect.” Yet her diamond and emerald tiara proved an unwelcome burden. Austria was the largest European state except for Russia, and the once carefree Sisi became the Empress of her own country, as well as the kingdoms of Hungary, Bohemia, Bavaria, and other regions that held fifty million subjects.

Terrified of intercourse, Sisi spurned the advances of her groom for three nights. When consummation occurred, the act became the topic of conversation of the palace. The morning after, as with every morning thereafter, the imperial couple had breakfast with Elisabeth’s aunt/mother-in-law who asked intimate questions. People remarked of Sophie that she was “the only man at court.”

Franz Joseph worshipped his wife who declared she made him “as happy as a god,” but he was immersed in the gargantuan task of ruling the Habsburg Empire that was crumbling under the weight of open revolt. He worked on his wedding day, and his wife discovered that with her husband, country came first, his mother second, his wife, third. And while opposites attract, this did not prove the case with the royal couple. The emperor was dedicated to duty and convention; the Empress craved excitement and romance. Elisabeth felt stifled at living in a larger-than-life goldfish bowl governed by rigid rules of protocol and referred to the Habsburg Palace as her “prison fortress.” A small act of rebellion: Sisi refused to give away her shoes and boots after a single use, a royal ritual- and defiantly wore them for a month.

Motherhood might have proven an outlet, but the Archduchess assumed parenting duties of daughters Sophie and Gisela, and the long-awaited son and heir, the crown prince Rudolph. Denied a meaningful role, Sisi spent her time in her private suite, reading the works of Heinrich Heine and penning poetry on a desk that had belonged to a former Habsburg princess, Marie Antoinette. She used the pen name, Titania, from the character in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. She hardly ate while exercise became a mainstay of her daily regimen. In her quarters, she installed gymnastic equipment in order to maintain her waspish waist. To keep her flawless complexion, she slept with a mask made of raw veal. Renowned for her floor length tresses, her hairdresser worked on them for three hours a day, fashioning them into a braided crown. After discovering her husband’s infidelities when she came down with a venereal disease, Sisi took to travelling to far-flung countries such as Pompeii, Egypt, and Corfu; on the Greek island, she built a palace she named Achilleion after the mythological Achilles. The disconsolate queen remarked, “Every ship I see sailing away fills me with the greatest desire to be on it.” Guilt-ridden over the pain he had inflicted on his wife, Franz Joseph admitted he had “a debt of conscience her never could repay” and showered his consort with gifts, including star-shaped diamonds that she intertwined into her Rapunzel locks. Other trappings of her bottomless wealth were thoroughbred horses and vacations on yachts. Enamored of the sea, she had a tattoo of an anchor on her shoulder that might also have been a nod to the weighty mantle of royalty. Her husband footed all bills, asking only she spend time at his side. However, no matter where the Empress travelled, depression and mental instability hovered. As a result, Sisi took an interest in the new innovations in the treatment of the insane. Viennese Sigmund Freud would have been her best choice-and she toyed with the idea of opening her own psychiatric hospital. “Have you not noticed,” she once asked, “that in Shakespeare the madmen are the only sensible ones?”

As the years passed, the Empress asserted her influence; her most significant political act was to persuade her husband to grant Hungary a constitution that led to the Austrian- Hungarian Empire. The move lessened the couple’s issues and Sisi and Franz Joseph resumed their intimate relationship. Their fourth child, Marie Velerie, was born in Budapest.

There is a saying that it is not good to let too much light into the castle, a truth that applies to the Empress of Austria who endured crippling misfortunes. Her sister, Duchess Sophie, perished in a fire in Paris, her two-year-old daughter, Sophie, passed away from illness, her cousin King Ludwig’s corpse was found in Lake Starnberg-either from murder or suicide. No stranger to misfortune, Franz Joseph survived an assassination attempt, and his brother, Maximilian I, met his end through a firing squad in Mexico. The most devastating loss was the thirty-year-old Rudolph, the heir to the throne, perished in a hunting lodge at Mayerling, a small village southwest of Vienna. Beside his corpse was the naked body of the seventeen-year-old Baroness Maria Vetsera. News spread like the proverbial wildfire that Rudolph had shot his companion and then turned the revolver on himself. The double murder, shrouded in mystery, crushed his mother’s already bruised spirit, “Rudolph’s bullet killed my faith.” The crown prince’s passing irrevocably altered the destiny of an ancient empire-and that of the world. Succession ultimately passed to Franz Joseph’s nephew, the Archduke Francis Ferdinand, whose assassination in Sarajevo in 1914 led to the outbreak of World War I that signified the death knell of the Habsburg dynasty.

After the loss of her son, Elisabeth wore black for the rest of her life, refused to be photographed so she would be remembered at the height of her beauty, and travelled incessantly to distance herself from the pain of her past. She sojourned across Europe and North Africa, refusing imperial protection. In 1898, Sisi was in Lake Geneva, using an assumed name, where she travelled with a lady-in-waiting. Also in the city was an Italian anarchist, Luigi Lucheni, who had made his way to Switzerland to assassinate Prince Henri of Orléans in order to protest the royals he viewed as bloodsuckers. News of the crowned head in their midst leaked to a newspaper and unable to attack the French royal, Lucheni turned his sights on the Empress. As Sisi was about to board a steamship for Montreux, the assassin lunged at her that led to her death from internal bleeding ending her forty-four-year reign. Her dying words, “What happened to me?”

A train returned the Empress’ body to Vienna, and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire plunged into mourning; eighty-two sovereigns followed her funeral cortege to the Capuchin Church, the ancient Imperial Crypt of the Habsburgs. Unlike Sleeping Beauty who awoke from her slumber, Sisi never attained the fairy tale heroine’s Latin name for dawn: Aurora.