Triumph of the Will (1902)

The ancient Greek Menader wrote, “Whom the gods love die young.” The quotation applies to a 20th century woman who lived for over a century-the latter half under the cloud of colluding with the most evil regime in history. This raises the philosophical question: should we judge art on its own aesthetic or does its creator’s ethics come into play? Those who believe that a canvass should be divorced from the painter could make the argument the pyramids were constructed at the cost of the lives of thousands of Jewish slaves yet remain one of the Seven Wonders.

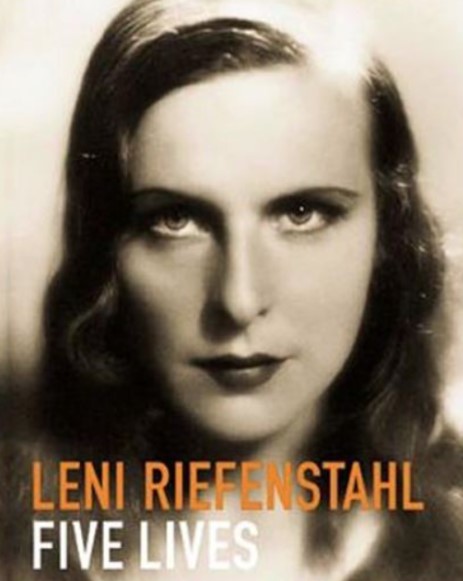

The woman- arguably the greatest of female directors- was born in Berlin as Helene Berta Amalie (Leni) Riefenstahl. Her surname, according to Google’s Instant Translator, means ‘scoring steel’ and to judge from her exploits the word fits. Although the family was affluent-her father Alfred owned a large heating and plumbing firm- she and her brother Heinz appeared unhappy in childhood photographs. Their misery was understandable as Herr Riefenstahl was a tyrant of the non-benevolent variety. His wife Bertha was not allowed money of her own and had to ask permission before going on any outing. Leni said this legacy left her with a sense of “screaming resistance.” No one could ever persuade Leni there was something she could not do and in her late teens she made up her mind to be a dancer. With her mother’s approval she secretly took lessons; when the truth outed the patriarch sent his wayward daughter to boarding school with instructions she be treated with severity, something her teacher chose to ignore. The teen directed and starred in plays; having hidden her ballet shoes she practiced every day. Leni gave her first recital in 1923 and her free style moves-in the vein of Isadora Duncan-caught the eye of producer Max Reinhardt. Under his patronage she undertook a highly successful European tour. While on stage in Prague she damaged her knee, abruptly ending her career.

Leni had also garnered notice because of her scandalous love life. Her first sexual experience was at 21-when she finally broke free of her father- with Otto Froitzheim- Germany’s most famous tennis champion-18 years her senior. She recalled he was wildly handsome but broke off their engagement due to his affair with actress Pola Negri. Her only walk down the aisle was with Peter Jakob, a career officer in the German army. To her great chagrin, his unofficial career was adultery and the couple divorced in 1946 though they remained together until 1952. Leni recalled, “He was my fate, my greatest love and greatest emotional tragedy.”

Despite the end of her dancing days Leni was not willing to play housfrau and cast her eye on another venue of artistic expression. Inspiration came when she saw an alpine drama filmed by Arnold Fanck. His movies, set against stunning natural backdrops, provided a distraction from the economic problems of the Weimar. Enthralled, Leni arranged a meeting with the director who was taken with her appearance and athletism. He wrote The Mountain of Destiny (1926) for her about a dancer turned mountain climber and several others followed. Her dangerous feats-she climbed mountains barefoot, survived avalanches and skied down slopes in a bathing suit-made her a star throughout Germany. Riefenstahl would have been a bigger success had she not lost the role of a cabaret singer to the unknown actress who lived in the apartment next to hers; the film was The Blue Angel; the actress, Marlene Dietrich. Despite her acclaim she felt her talent was best suited to work behind the camera and in her directorial debut The Blue Light a superstitious villager called the mystic mountain girl-played by Leni- “an accursed witch.’ Her films were praised by Charlie Chaplin.

It was in the year before Hitler’s rise to power that she first heard the Nazi leader speak at a rally. In her autobiography she wrote, “That very same instant I had an almost apocalyptic vision that I was never able to forget. It seemed as if the Earth’s surface were spreading out before me, like a hemisphere that suddenly splits apart in the middle, spewing out an enormous jet of water, so powerful that it touched the sky and shook the earth. I felt paralyzed.’’ Leni, just before she was to leave for several months of production in Greenland, wrote to the future Fuhrer she was smitten with his speech and wanted to meet him. Hitler, another of her fans, agreed. At their 1932 encounter he told her that her dancing was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen and promised, “Once we come to power, you must make my films.” Although Leni was one of the century’s great beauties Hitler did not view her in an erotic light-though the same was not true of Joseph Goebbels. He hounded her through the years to be his ‘second wife.’

In the 1930s Riefenstahl won the tyrant trifecta. Stalin sent her a note praising her film Olympia, Mussolini asked her to make a documentary, and Hitler was her patron for three movies about his party. Her 1934 film on the Nuremberg rally provided a glimpse of the Third Reich in its strutting infancy. Her revolutionary approaches remain unquestioned-it stands with Battleship Potemkin as the most masterly propaganda film ever made-the problem was the star of the show was Adolf Hitler. He described her movie as “a totally unique and incomparable glorification of the power and beauty of our Movement.” Although in terms of artistry it was a masterpiece it forces the examination the relationship between art and accountability. Amidst great acclaim Leni went on tour to the Venice Biennale, throughout Europe and to the United States. Her arrival coincided with the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht and Riefenstahl was met with hostility, only Walt Disney publicly received her. Leni said she refused to listen to the rumors, ones undoubtedly spread “by the Jewish moneymen.” On the outbreak of the war Leni turned her hand to reporter; however, after witnessing the massacre of Polish Jews she was appalled and retreated to Spain.

It was Ms. Riefenstahl’s fate to not only survive WWII but to live on and on and on as a pariah. In 1945 the Allies denounced her as a Nazi sympathizer and placed her under house arrest. One of her captors was screenwriter Budd Schulberg who dubbed her “the Nazi pin-up girl;” newspaperman Walter Winchell called her ‘pretty as a swastika.” Amidst widespread skepticism she insisted she was apolitical-despite her fondness for reading Mein Kampf on the set-and was motivated only by her artistic muse. As she had never been a member of the Nazi party after four years of incarceration-first by the Americans then by the French- the authorities cleared her of war crimes. Although free her reputation remained sullied with her undeniable role in helping to make an awkward little man into a demigod. Repeated attempts to obtain financing for a new film proved futile and any pubic showing of a Riefenstahl film prompted protests. Her talent had become her tragedy. Devoid of work she spent the next 20 years in relative isolation, living in her mother’s apartment in Munich, trying to shed her image as the Nazi regime’s most persuasive propagandist. Although she engaged in many post war pursuits her chief one was devoted to fortifying her legend and to suing her detractors. Over the years she won more than 50 actions against those who alleged she had always known the truth. Although legally vindicated she groused, “But the lies always stick.” She also tried to disinherit her only living relatives, a niece and a nephew, with a spurious will that laid claim to her brother’s estate. Leni used the fact that her relationship with Hitler did not extend beyond the professional as her plea to save Heinz from the Russian Front-where he died- fell on deaf ears.

A major revival of interest in Riefenstahl occurred in the early 1990s when international stars such as tennis player Boris Becker flocked to her 90th birthday party. The celebration took place in a hotel on the Starnberg Lake, an establishment frequented by Bavaria’s richest. Helmut Newton photographed her for Vanity Fair, and Ray Muller’s documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl featured a lengthy interview with the defiantly unapologetic nonagenarian. Not surprisingly, Leni was eager to set out her version of the truth and turned author when, at age 90, she penned her memoir. Its epigraph was a complaint of Einstein’s, “So many things have been written about me, masses of insolent lies and inventions that I would have perished long ago, had I paid any attention.” In her book-devoid of humor- she countered the old accusations that painted a picture closer to myth than history. Its 700 pages are filled with the crosses she had to bear such as her terrible American captors who showed her pictures of concentration camps. The New York Times book reviewer, John Simon, said it did not contain “a single unspellbinding page.” Although he questioned its veracity he concluded, ‘The book must, in the main, be true; it is far too weird for fiction.”

In a nod to you can’t keep an iron-willed woman down at an age when other women are reaching for their knitting needles she took up scuba diving, claiming only to be 51-when she was actually 20 years older-in order to obtain a diving license. Two collections of her underwater pictures “Coral Gardens” and “Wonders Under Water,” came out in the United States and she continued diving in the Maldives until she was in her late 90’s. In 2002 she released her first movie in almost half a century, a 45-minute documentary of marine life called “Impressions Under Water” that qualified her as the world’s oldest film director. It is a series of breath-taking images of the unpolitical life under the sea-interspersed with shots of Ms. Riefenstahl petting rays. It seemed as if time had forgot Leni as she looked fetching in flippers and a wetsuit. The film is also a nod to her films had been more about narcissism than Nazism.

However, it was her photography that stirred up her old nemesis-controversy. Inspired by Hemingway’s The Green Hills of Africa she became enamored of the continent and made several trips to southern Sudan to photograph its indigenous people-as she had once down with Aryan athletes. There she boogied with the Nuba maidens and travelled extensively, usually clad in Versace leggings. Initially she worked alone but was later joined by her lover Horst ‘Horsti’ Kettner, who she lived with for the rest of her long life. In March, 2002, while on a return visit to the Nuba, the 97-year-old Ms. Riefenstahl was severely injured in a helicopter crash that came under fire in the war-torn Sudan and had to be flown to a hospital in Munich. The pain of her physical injuries required morphine, but the stab wounds of her persecutors-as she regarded anyone who questioned her blameless version of the past- were harder to anesthetize. Her first Sudan book, “Last of the Nuba” published in 1974, won her recognition as a photographer and to some extent rehabilitated her as an artist. She felt a sense of vindication when her native land once again praised her as the most important female director. Leni also photographed the ill-fated Munich Olympics where terrorists murdered the Israeli wrestling team.

Riefenstahl’s detractors continued with their “J’accuse!” but a new and mainly American audience embraced the woman who showed the artistry of a D. W. Griffith. Among her fans were the organizers of the first Feminist Film Festival who hailed her as a female director role model. On a technical level this was understandable and yet the irony was she had been the handmaiden of a regime that had glorified violence and heavily leaned towards misogyny. L. Ron Hubbard briefly collaborated on a remake of The Blue Light, Mick Jagger invited her to take his picture with wife Bianca, and Andy Warhol added her to his list of muses. Jodie Foster aspired to direct and star in her life story but Leni refused, “Jodie’s not beautiful enough to play me.” Instead, Riefenstahl suggested she be portrayed by Sharon Stone as she had appeared in Basic Instinct. Another objection to a Foster production was Leni felt Jodie “Doesn’t want to do the memoirs. She wants to do the rumors.” George Lucas praised her modernity and in 1998 Riefenstahl was one of the guests of honor at Time’s seventy-fifth anniversary banquet.

Leni spent her later years in Pocking, her light-filled home south of Munich in the Bavarian Alps where she and Horst moved in 1979. She remarked of her two great loves, “I cannot imagine my life without him, or without this house.” She remained slim and blonde and her legs, quite as famous in her heyday as Dietrich’s, stayed shapely. To the end she continued to plead naivety- and with advancing age and morphine for her bad back- a simple failure of memory. Finally, after joining Greenpeace and after celebrating her thirty-fifth anniversary with Horst, she died in bed at age 101-living, working, loving, and litigating until her heart of steel gave out. Her epic film could well have served as her epigraph, Triumph of the Will.