The Truth (1903)

“C’est mon Plaisir” “It is my pleasure.” Isabella Stewart Gardiner

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

25 Evans Way, Boston, Massachusetts

Gods behaving badly is exemplified in Titian’s 16th century painting, “The Rape of Europa.” The canvass reveals Zeus, in the form of a bull, ravishing the maiden. The masterpiece served as the crown jewel in Isabella Gardner’s art gallery, the scene of a violation that involved the art world’s greatest whodunit.

The consummate collector, one of Isabella Stewart’s treasures was lace. Among her most precious was a tattered fragment of sixteenth-century Belgian material, once the possession of Mary Stewart, Queen of Scots. The artifact’s appeal: Isabella professed she was a descendent of the royal despite the different spellings of their surnames. To bolster the blueblood connection, Isabella obtained William Ward’s 1793 Mary Queen of Scots Under Confinement.

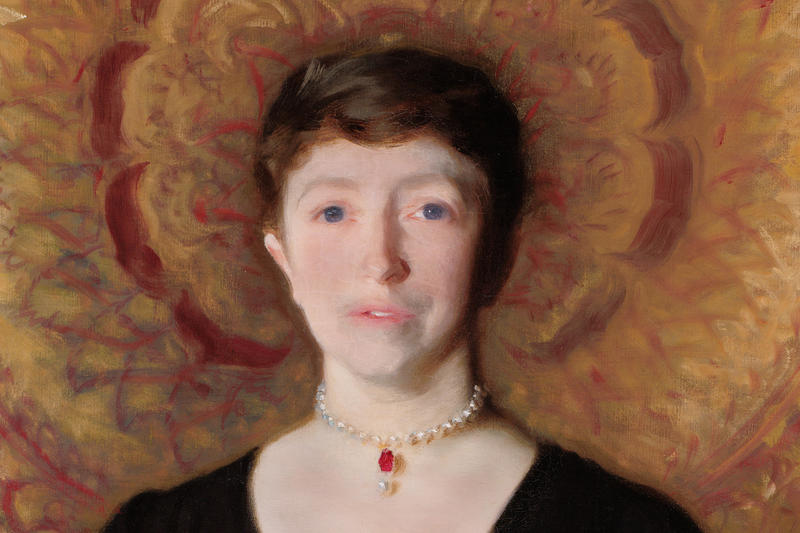

Although not a descendent of Mary, Isabella’s family had their roots in Scotland. The ultimate aesthete was born in New York City in 1840, the eldest of four children of Adelia and David. Although her facial features were plain, she had curves for which kings have scorned their scepters. A friend from her French finishing school, Julia Gardner, introduced Isabella to her brother, John “Jack” Lowell Gardner, Jr. A Boston blueblood, he was the city’s most eligible bachelor.

A few days before the bride’s twentieth birthday, the couple married in New York City’s Grace Church. A wedding present from the father of the bride was a home in pricey Back Bay from where she juggled Brahmin and Bohemian Boston. Known as Mrs. Jack, Isabella specialized in scandalous behavior. As the Bostonians were either Unitarian or Episcopalian, she presented herself as a Buddhist. Newspapers carried articles on Isabella taking Rex, a lion from the Boston Zoon, on walks down Commonwealth. A sports fan, she attended the symphony with a hatband inscribed, “Oh You Red Sox.” A pair of large diamonds mounted on springs served as antennas. A culture vulture, Isabella dined with Oscar Wilde who sent her a copy of his scandalous poems to his lover, Alfred Lord Douglas. Other notable friends were Julia Ward Howe, Henry James, and T.S. Elliot.

Another thumbing of nose at sedate society manifested itself in John Singer Sargent’s 1888 portrait where he accentuated his model’s hourglass figure with a skintight black dress plunging neckline. At Jack’s request, Isabella reserved the painting for their private viewing.

There are innumerable photographs of the heiress: with dogs, Kitty Wink and Patty Boy, in Norway, on a horse-drawn cart, in Italy, on a gondola. However, the only picture where Isabella radiated joy was holding John “Jackie” Lowell Gardner III. After his passing from pneumonia just before his second birthday, Isabella fell into a deep depression. To restore his wife’s spirit, John arranged a trip abroad and ultimately the couple visited thirty-eight countries.

Her father’s will, coupled with Jack’s fortune, left the Gardner’s with a contemporary fortune of approximately $200 million that led to Isabella’s vocation. She bought art ranging from rare books, antique tchotchkes, to Old Masters. One purchase occurred at a Paris auction where she arranged a signal with a dealer who bid on her behalf. She had instructed him to keep raising the stakes until she lowered her handkerchief. She outbid the Louvre and London’s National Gallery.

After the death of her husband from a stroke, Isabella suffered a nervous breakdown. For an outlet, she founded a museum-the first American woman to do so-to showcase her treasure chest that included letters from Napoleon, Beethoven’s death mask, and medieval rosaries. Boston buzzed over Mrs. Jack’s “Eyetalian palace.” Fenway Court, named after its locale, consisted of the façade of the Venetian palace Ca’d’Oro and held remnants of old Italian palazzi-staircases, fountains, and balconies. The exterior displayed a coat of arms that featured a phoenix rising from the ashes. From the balcony, one can envision the gondolas of the Grand Canal. Along with her pet terriers, Isabella moved into the Fenway’s fourth-floor apartment.

Eschewing a museum-like austerity, her gallery resembled a home-one that held canvasses with the names of the Old Masters. Hence, there were no plaques beside the paintings, and Isabella displayed family photographs and cherished novels throughout. Cases held the doyenne’s correspondence with Johannes Brahms and Franz Liszt in proximity to classics such as Edgar Degas’ ballerinas. The marble staircase features an ornate wrought-iron railing made from the bedframe from an Italian convent. A Roman mosaic of Medusa’s head dominates the magnificent garden. A journalist described the structure, “no less an artwork than the art itself.”

Hundreds of bluebloods attended the grand opening of The Fenway to the strains of the Boston Symphony’s overture to Mozart’s Magic Flute. A thousand candle flames flickered in front of priceless displays. Lanterns illuminated the arched windows and the Fenway’s eight balconies. Sheathed in black gown and draped in pearls, Isabella greeted her guests. In 1924, Isabella passed away in her fourth-floor apartment. Her interment was in the Gardner Family Tomb in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she lies between her husband and son.

In charge of her museum even upon her death, In her will, Isabella instructed her trustees to hold an annual memorial service to commemorate her April fourteenth birthday in her chapel that holds thirteenth century stained-glass windows. Another caveat directed the museum to change her institution’s name to her own. The third decree: should anything leave or be added to her collection, or if her placement of objects be altered, a Paris auction would sell her possessions with the proceeds earmarked for Harvard University.

Her edict-regarding nothing be removed, ended on the costliest St. Patrick’s Day in art history. Two thieves, disguised as police officers, pretended they were investigating a disturbance. Once inside, they shoved two guards against the wall and announced, “Gentlemen, this is a robbery.” Leaving the guards bound with duct tape in the basement, the pillage continued for eighty-one minutes. The thieves walked out with thirteen masterpieces and into the annals of one of the world’s most infamous mysteries. They left behind Whistlers, Raphaels, Sargents, and a Michelangelo Pietà sketch. The interlopers failed to snatch “The Rape of Europa.” Underneath the Titian, Isabella had placed a framed swatch of silk from her Worth of Paris gown. The museum had not insured their property.

Thirty-three years later, heavy gold frames showcase green brocade wallpaper where jewels of art once hung. A plaque reads: Stolen, March 18, 1990. Despite a ten-million-dollar reward, the perpetrators of the heist, and their ill-gotten gains, (estimated at a worth of half a billion dollars,) remain missing. Visitors must rely on imagination to visualize Vermeer’s “The Concert,” to picture Rembrandt’s only seascape, “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” One can also hear heart-rendering cries from Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Guests of the museum, surrounded by the founder’s mementoes, might feel they know Mrs. Jack. However, perhaps no one really knows Isabella, considering her quote, “Don’t spoil a good story by telling the truth.”