The Salt is Sugar (2013)

“Two hundred women, no phones, no washing machines, no hair-dryers, it was like Lord of the Flies on estrogen.” Piper

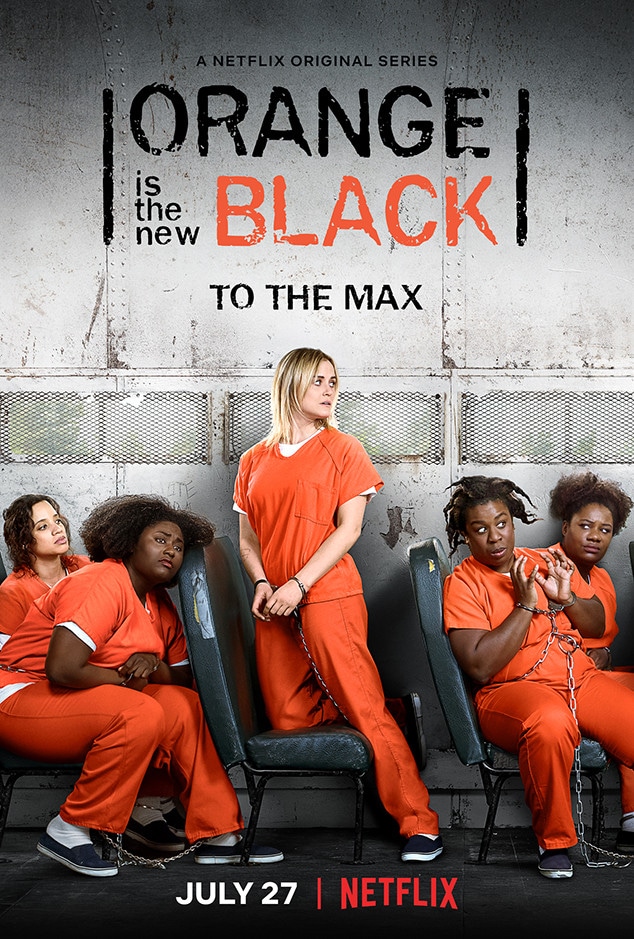

Television series centering on female friends? check; on family dynamics? check; on landing Mr. Right? check. Not until the arrival of Netflix’s dramedy, Orange is the New Black, did the small screen turn to the hell of incarcerated women.

Piper Kerman’s 2010 best-selling memoir, Orange Is the New Black: My Year In A Woman’s Prison, (orange is the color of the jumpsuits worn by new inmates,) served as the catalyst for producer Jenji Kohan’s Netflix series. The plot centered around Piper, a privileged, college-educated, white woman, (her nickname is College,) the antithesis of a typical American prisoner. Piper was enjoying a Brooklyn, bourgeois bohemian lifestyle with fiancé Larry when she discovered the truth of William Falkner’s quote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” During her wild-child years, Piper had served as a one- time mule at the insistence of Alex, her drug-trafficker, lesbian lover. Her crime caught up with her ten years later for which she received a fifteen-month sentence. Larry was gobsmacked that his yuppie girlfriend’s closet carried skeletons in which hung an international drug ring and a same sex relationship.

An early concern regarding separation from Larry is that he would watch Mad Men without her; however, Piper soon had far more to worry about than if he watched it while canoodling with another. In the first episode, Piper arrived at Litchfield Penitentiary in upstate New York that could have displayed a sign from Dante’s Inferno, “Abandon hope all ye who enter here.” Or, as prison pal Nicky put it, “It’s just like the Hamptons, only fucking horrible.”

During the opening credits of Orange, (the shorthand used by those associated with the show,) Regina Spektor crooned, “You’ve got time.” For the ladies of Litchfield, that’s not a comforting thought; the sands of the hourglass slip at a snail’s pace in an institution indifferent to prisoners’ pain. Alongside the lyrics, a photo montage scrolls through female faces absent from prior series: Latinas, lesbians, blacks, immigrants, elderly, the mentally ill, and those with double-digit dress sizes. The motley crew are as memorable as their names: Crazy Eyes, Yoga Jones, Red, Taystee, Miss Claudette. Although the show centered on WASP Piper, her fellow inmates shared time in the glaring searchlights of Litchfield. Those with whom the former Brooklyn-based Piper resides: an activist nun, (based on Sister Ardeth Platte, a Dominican Sister who spent years imprisoned for her anti-nuclear activism,) a slave-operator turned murderer, as well as former lover, Alex. We learn that most of the prisoners’ legal woes stemmed from drugs, covering up for a man, and abusive relationships. As Poussey stated, “We’re all just here because we took a wrong turn going to church.” Carnality also proved irresistible catnip to the series that explored the sexual shenanigans of the prisoners who were either transgender, straight, bisexual, or gay. Other’s sexual identity is expressed by the slogan, “gay for the stay, straight at the gate.” The show carried the disclaimer, “Language, sex, nudity, suicide, smoking.”

Through flashbacks, the audience learns the women’s backstories that wove a sad and strange tapestry. Red, (a nickname based on feistiness as well as hair color,) lord of the prison kitchen, was doing time for her role in the Russian Mafia. Before her incarceration, after a fellow Russian woman had dissed her, Red punched her in the chest that destroyed her breast implant. Not mellowed by life behind bars, when Piper conversationally remarked that the food was shit, Red ensured Piper received a used tampon sandwich, and was denied access to future meals. Sophia is a former firefighter, transgender woman who committed credit card fraud to finance her sex-reassignment surgery. The prison officials cut off her hormone pills that left her in the purgatory of an intersex existence. In this Twilight Zone universe, a stick of gum could ignite a romance or a death threat.

If dealing with desperate fellow prisoners was not horror enough, there is also the matter of sadistic guards, represented by Officer Mendez, the correctional officer dubbed Pornstache, a nod to his moustache and his prurient habits. He smuggled drugs into Lichfield and had sex with the women who he felt should be grateful for his amorous attention.

Alongside the correctional officers and the inmates there is another Litchfield inhabitant, a chicken whose capture became the prisoners’ Holy Grail. Red wanted to turn the fowl into a savory meal; others believed money or drugs were hidden in its cavity. The chicken held metaphorical significance: it is a female, confined creature, unable to fly from its enclosure. Eventually, the chicken assumed legendary proportions as a talisman of what was the only good thing in Pandora’s Box-Hope.

Despite the bleakness one of the ways the jumpsuit-clad women survive is through female friendship. Orange puts the mate in inmate. Although often at each other’s throats, they also have each other’s backs. The gal pals share a coveted Mac N Cheese, go after enemies with makeshift shivs, use cockroaches to carry contraband to one another’s cell. Take that Laverne and Shirley!

As with other great television, Orange both entertains and delivers important societal commentary. While incarceration is not supposed to resemble a walk in the park, it nevertheless should not be designed to crush inmates’ souls. The original name of prison was rehabilitation centers-and yet they have transformed into instruments of retribution.

The flashbacks humanized the woman, and helped viewers understand the realization, “There but for the grace of God goest I.” Would we be on the other side of bars had we not been born to supportive families, money, and therapy? Would we have ended up Litchfield if we had lacked impulse control, or had made a disastrous youthful decision? The overriding message of Orange is that prisons should be restorative, not punitive. As Jenji put it, “You are not your crime.” After concluding its seventh season, Jenji stated, “It’s time to be released from prison. I will miss all the badass ladies of Litchfield. My heart is orange but fade to black.”

The creative force-and force of nature behind Orange has hair, if not orange, has many other hues such as blue, green, pink and purple, and multi-colored. Her mother, Rhea, claimed the name Jenji came to her in a vision as a derivative of Jennifer. Jenji grew up in a Jewish family in Beverley Hills; her father, Buz, was a writer for the Carol Burnett Show. Rhea, employed parenting gems such as, “I’ll buy you those expensive jeans when you’re thinner.” As a teenager, Rhea dragged her to several plastic surgeons, but Jenji refused their services. She attended Columbia, and worked creating script for the NBC sitcom, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. As one of only two female writers, and the only white woman, her nickname was White Devil Jew Bitch.

Jenji’s charmed life took a beating when her twenty-year marriage to Christopher Noxon-whose sister Marti was the creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer- ended in divorce. In 2020, while Christopher was on a vacation with their three children, their twenty-year-old son, Charlie, died in a New Year Eve’s ski accident.