The Last Word (1501)

Kings are subject to grand gestures, sometimes of a romantic nature. Legend holds that when Queen Amytis grew homesick for the lush landscape of her native Media, her husband, King Nebuchadnezzar II, commissioned the Hanging Gardens of Babylon in his desert kingdom. When Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to their fourteenth child, Shah Jahan immortalized his wife with the world’s most magnificent mausoleum. King Edward VIII, urged to give up his mistress, Wallis Simpson, instead relinquished the British throne. Another crowned head changed his country’s religion to legalize his obsession.

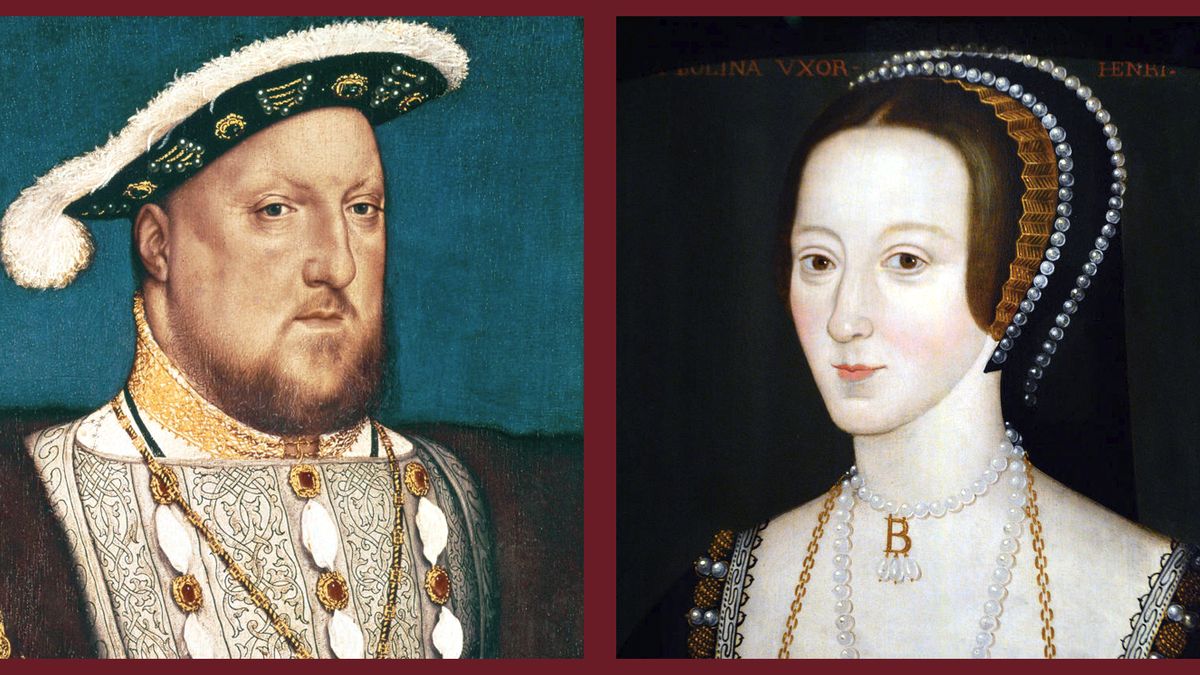

The most colorful and controversial of Henry VIII’s six wives was the daughter of Sir Thomas Boleyn, a prominent courier, and his highborn wife, Lady Elizabeth Howard. Along with her sister, Mary, and brother, George, Anne grew up in the imposing Hever Castle in Kent. George and Anne were exceedingly close while the sisters’ relationship was marked by rivalry. The ever-ambitious Thomas used his diplomatic connections to secure his daughters’ appointments in the French court presided over by Henry’s sister who briefly occupied its throne. When Mary returned to England, she served as a maid of honor to Henry’s Spanish-born wife, Catherine of Aragon. In her off-hours, Mary also became Henry’s mistress; rumor had it she bore him a son. As the merry monarch’s romantic relationships came with an expiration date, he pawned her off to William Carey, a younger son without fortune or land.

Another reason Henry severed their sexual strings was because he had become infatuated with Anne who he eyed as a future lover. In order to facilitate this end, he sabotaged Anne’s romance with Henry Percy, the heir to the vast Northumberland earldom. Although not conventionally attractive, Anne exuded sexuality in spades, a trait for which scepters have been tossed aside. The object of his lust had a swarthy complexion, long nose, and her bosom was “not much raised.” In addition, she had a large “wen,” (mole) on her neck-the reason she favored necklaces- and a sixth finger on her hand. Determined not to become another abandoned Boleyn, Anne retreated to Hever Castle where Henry sent her lovesick letters. He wrote he was “Wishing myself (especially of an evening) in my sweetheart’s arms whose pretty duckies I trust shortly to kiss.” The swain signed off, “Your loyal servant.” The first missive came with a gold bracelet that held a picture of the king. Anne’s refusal to embark on an affair fanned the flame of Henry’s passion. By sticking to her virginal gun, Anne triggered one of the most monumental events in British history.

The impediment to legitimizing their relationship was Henry’s twenty-four-year marriage to Catherine for whom he no longer felt an attraction. Equally damning, he felt she was to blame for failing to produce the male heir to perpetuate the Tudor dynasty, (Henry felt women did not capable rulers make). Henry’s plot to extricate himself from his starter wife led to a series of events dubbed the “King’s Great Matter.” His justification to dissolve his marriage was his Spanish consort had been his brother Arthur’s widow, and therefore, the marriage flew in the face of Leviticus that forbid the bedding or wedding of a brother’s spouse. The king’s men, the medieval dream-team: Cardinal Wolsey, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, and Sir Thomas More- badgered Pope Clement VII to grant an annulment. Had it not been for the Pope’s refusal, Britons would be eating fish on Fridays and would be birthing far more children. In a nod to what Henry wants Henry gets, in a time-honored move, he replaced his menopausal spouse with a fertile one; however, in this instance, doing so meant breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church. He converted England to the Protestant religion and gave himself the titles of the Supreme Head of the Church of England and Defender of the Faith. By negating his marriage, his daughter, Mary, bore the brunt of illegitimacy. The king’s act set the stage for years of bloodshed between the two warring religions.

Free of Catherine, Henry married Anne and showered his ladylove with jewelry such as gold and diamond bracelets, pendants with their intertwined initials, and blood-red rubies. Henry also bestowed upon Anne the title of Marquess of Pembroke, an honor that made her the most prestigious non-royal woman of his realm. His father-in-law became the Earl of Wiltshire, and he appointed her brother to the Royal Privy Chamber. The coronation of the new queen proved the pinnacle of pageantry in which fifty barges, adorned with flowers, streamers, and flags escorted the newly minted royal along the Thames River to the Tower of London where she awaited the official ceremony. Carried aloft on a litter of gold and white, adorned in a crimson gown encrusted with precious stones, in Westminster Hall Anne walked over a blue cloth to the Archbishop of Canterbury to receive the crown. If all the splendor was not heady enough, Anne was five months pregnant. The Tudors were gravely disappointed with the arrival of Elizabeth rather than the longed-for male heir.

The Brits did not view Anne as the people’s princess; rather, they considered her a harlot who had usurped the rightful queen, and whispers abounded over the “goggle-eyed whore.” They also detested her for her role in the country’s break from Rome that reduced the United Kingdom to a state of civil war. Anxious to stifle hostility against the woman he loved, Henry warned that there was “no head so fine that he would not make it fly.” Further trouble infiltrated the castle when Anne suffered miscarriages (one occurred on the day of Catherine’s funeral at Peterborough Abbey when the queen gave birth to a stillborn son). Fights between the royal couple erupted, and Henry despaired of ever taming his shrew. With the waning of their sexual and interpersonal chemistry, Henry’s wandering eye wandered to a lady-in waiting. By marrying her lover, Anne had created a vacancy for a new mistress.

Henry and Anne’s relationship had commenced with a jewel, and its demise ended with another. Lore holds that Jane Seymour, literally and figuratively a lady-in-waiting, hovered in the wings to supplant Anne. The queen discovered her husband’s new flame when she saw Jane wearing a locket with a picture of Henry inside. Once again Henry kept his relationships in the family; just as he had bedded the Boleyn siblings, Jane was related to Anne through their shared great-grandmother. The rivals possessed very different personalities: Anne was outspoken and volatile; Jane was docile and anxious to please. Their different temperaments were apparent from the mottoes they adopted when they wore a crown. Anne chose the phrase, “Ainsi sera, groigne qui groigne,” (That’s how it’s going to be, however much people might grumble). Jane chose, “Bound to Obey and Serve.” The possessor of a sadistic streak, to torment her rival she took to opening and closing the locket, a move calculated to enrage the queen.

In a nod to King Henry II’s words regarding Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” Henry decided it was time again to discard an inconvenient wife. Henry charged his wife with adultery with five men, incest with her brother, as unable to control her “carnal lusts,” and treason against the king. Her large mole and sixth finger were used as signs of witchcraft. Anne ended up in the Tower of London, this time to wait her execution rather than her crowning. The trial, in which guilt was a foregone conclusion, resulted in the death sentence of the queen, accused of seducing Henry through sorcery, along with her lovers. While Anne had been the object of Henry’s desires for several years, her reign lasted for three years that led to her moniker: Anne of the Thousand Days.

One can only image the horror Anne endured in the Tower, separated from her only child, Elizabeth, who would be deemed illegitimate and mocked as the daughter of a witch, shorn of her once magnificent possessions, facing execution at the hands of her husband. She said of Henry, “The king has been very good to me. He promoted me from a simple maid to a marchioness. Then he raised me to be a queen. Now he will raise me to be a martyr.”

The method of death by burning or beheading was at Henry’s discretion, and he chose what he felt was the most humane execution. He sent for “the Hangman of Calais” whose swordsmanship ensured it would take only one blow to sever the neck while an axe often took several. On hearing her fate, Anne remarked, “I have heard say the executioner was very good, and I have a little neck.” While Henry’s decision might seem to have been the most compassionate alternative, it was probably more of a bid at self-aggrandizement. Henry often claimed he was a descendent of King Arthur, and thus the sword was a nod to Excalibur, the symbol of sovereignty in Camelot. Or, perhaps, Henry still harbored feelings for the wife for whom he had undergone papal excommunication.

On the date of the execution, in the Tower Green, guards opened the gates and a crowd of a thousand, (Henry was not present), gathered to watch the dispatching of their former queen who still wore a royal garb of black damask over white ermine. On the scaffold, Anne did not protest her innocence, did not rail against the man who had split Christian Europe apart to make her his bride, who had condemned to death her hapless brother. Her praise for the architect of her murder was a final ploy to her protect her young daughter, “For a gentler nor a more merciful prince was there never: and he was ever a good, a gentle and sovereign lord.”

After the Hangman of Calais finished his historic gesture, Anne’s eyes and lips still moved as her head landed on the straw. True to form, Anne had the last word.