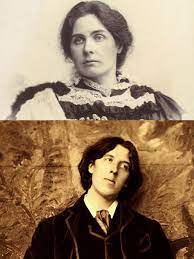

The Importance of Being Constance: Mrs. Oscar Wilde

The 17th century fictional Hester Prynne was forced to wear a scarlet letter for running afoul of Puritan Boston; her life closely paralleled the 19th-century nonfictional Irish writer, Oscar Wilde, who thumbed his nose at the rigid rules of British society before Queen Victoria’s un-amused eyes. In both cases, they were more sinned against than sinners. But there is one who was more sinned against than all: Oscar Wilde’s little-known wife.

No one was ever more suitably christened than Constance Lloyd, whose constancy would be tested through a seemingly masochistic fidelity to an irresponsible, brilliant literary husband. She was born in 1858 in Dublin in an upper-middle class family. Their house was elegantly appointed but her father, Horace, a Queen’s Counsel, was an absentee parent who had been arrested for exposing himself to nursemaids. () Family life further deteriorated when he passed away when Constance was sixteen, leaving her in the clutches of mother, Ada. Like the Queen in Snow White, Ada Lloyd bitterly resented her daughter’s beauty which had eclipsed her own. The girl’s life-preserver was brother Otho, who arranged for her to live with their paternal grandparents before he departed for Oxford.

Constance had the usual ladylike accomplishments-playing piano, painting, needlework, but she aspired higher: reading Dante in Italian and taking a university class on Shelley in an era when women were not allowed to earn degrees. Soon the bohemian-dressed beauty was attracting admirers of all types. But she preferred artistic bad-boy types and fell passionately in love with the king of them all: Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde. They shared the commonalities of Dubliners, children of professional fathers who were arrested on sexual charges and Freudian Dream mothers.

Constance felt an instant connection when she discovered Oscar, a flamboyant man-about-town, had a deep admiration for Keats, and listened intently about his pilgrimage to the Protestant Cemetery in Rome where he had laid flowers on his idol’s grave. He ended the evening by whispering she was poetry incarnate; hearts have surrendered for far less. On the drive home he told Lady Wilde, “By the by, Mama, I think of marrying that girl.”

Unaware of his words, Constance worried he was either being flirtatious—as he was known as a ladies’ man, keeping company with beauties such as Sarah Bernhardt and Lillie Langtry—or still on the rebound from Florence Balcombe, who had ended their relationship when she married Bram Stoker, master of the undead, author of Dracula. After Oscar’s visit to the Lloyd home for tea, she wrote Otho, “O. W. came yesterday at about 5:50 (by which time I was shaking with fright,) and begged me to come and see his mother again soon. I can’t help liking him, because when he’s talking to me alone he’s never a bit affected, and speaks naturally, excepting that he uses better language than most people.”

Their courtship was curtailed when Wilde left to the States on a lecture tour which made him famous on both sides of the Atlantic and allowed him to deliver his bon mot in the New York City Customs, “I have nothing to declare but my genius.” It also allowed him to indulge in his favorite pastimes of talking to captive audiences and meeting celebrities: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendall Holmes, and Walt Whitman, (the latter of whom declared Oscar ‘a great, big splendid boy.’) Two years later Constance wrote Otho, “Prepare yourself for an astonishing piece of news. I’m engaged to Oscar Wilde and perfectly and insanely happy.” Otho sent his Irish version of mazel tov by the next post, “If Constance makes as good a wife as she has been a good sister to me, your happiness is certain. She is staunch and true.” On May 29th, 1884, at 2:30 P.M. Constance and Oscar, wearing matching bands designed by the groom, exchanged vows at St. James’ Church, Sussex Gardens.

Their Cloud Nine continued with a Parisian honeymoon in a flower-filled hotel suite overlooking the Tuileries. Upon their return, they leased a property on 16 Tite Street in the artistic neighborhood of Chelsea: residents included Carlyle, Rossetti, Whistler, and Stoker. The Wildes lavished attention on each avant-garde detail till Oscar deemed their temple to aestheticism “The House Beautiful.” Invitations to their dinner parties, (dubbed “At Homes,”) were coveted and the famous gathered in their salon to revel in the company of history’s most brilliant conversationalist. At gallery openings Mr. and Mrs. Oscar, (name bestowed by the press,) proved stiff competition to Lillie Langtry as the main magnet for celebrity watchers.

During this golden era Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray and fairy tale, The Happy Prince, dedicated to his spouse who he addressed as ‘the great lamp of a cathedral shrine,’ and The Selfish Giant, a story of Christian redemption. Constance, not wanting to be her husband’s ornament such as his omniscient green carnation, tried her hand at writing as well. Although her talent did not match Oscar’s, (whose did?) published a book of children’s tales entitled There Once Was. An ardent feminist, she was a member of the Rational Dress Society which likened corsets to binding women’s’ feet and advocated the fairer sex should not be expected to don undergarments weighing upward of seven pounds (although they stopped short of burning bras). She was also a patron of Dorothy’s Restaurant where women could dine and, more shockingly, smoke alone. Most evenings found the couple together and when Oscar left on business to Scotland he wrote, “I feel your fingers in my hair and your cheeks brushing mine. The air is full of the music of your voice, my soul and body seem no longer mine, but mingled in some exquisite ecstasy with yours.”

Oscar, who adored all experiences novel, added another to his life’s résumé, fatherhood, with the arrival of sons Cyril and Vyvyan. The proud new papa could not stop urging his male friends to wed, and told Constance, “I feel incomplete without you.” The Wildes dwelled in their Tite Street Eden until Lilith, Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed Bosie, entered their garden. He was a beautiful aristocrat, (he had coined the phrase ‘the love that dare not speak its name,’) who could twist Oscar around his bejeweled finger- and quickly did.. Douglas was also a practicing homosexual and he chose to practice with Wilde, who proved to be quite open to the opportunity. Post Bosie, Oscar’s two hit plays, The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband, took on ironic overtones.

Wilde felt he was a rope in a tug-of-war-between his wife and lover, and it was the narcissistic Lord Douglas who proved victor. On one occasion, after spending nights in a hotel room (claiming he needed solitude to work), he returned home to spend time with his children and found an opportunity to pull the wool over Constance’s eyes. After reading them a story, he admonished his sons about naughty boys who make their mothers cry; Vyvyan asked what happens to absent fathers who make their mothers cry. For once Oscar was bereft of words..

Libido triumphed guilt and Wilde continued his affair. His quip, “In married life three is company and two is none,” had chillingly transformed into truth. Bosie brought out all of Oscar’s worst qualities, especially his selfishness and narcissism, which his wife had tempered. Besotted, he spent wildly on his young lover, buying costly cigarette cases and taking him to dine at the Café Royale and suites at the Savoy Hotel. As with everything else, he indulged in a lavish mid-life crisis. Constance, eventually forced from denial, confided to a friend, “I know that the one I am jealous of fills a place I cannot fill,” and determined to continue her marriage; although it was devoid of sex, it still possessed love.

The turning point in the ménage a trios occurred when the Marques of Queensbury, Bosie’s father, left a calling card-replete with misspelling- at Wilde’s club: “For Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite.” Bosie convinced Oscar to press a charge of libel against his despised father. The problem? Oscar was guilty of the accusation and in London’s high society it was an open secret. The trial was sensational, involving the peerage, the celebrity playwright, and rent boys (male prostitutes). However, lost in the shadows was Constance who faithfully appeared each day at court. What added to her mortification of being the spouse of Europe’s most infamous homosexual was extreme physical anguish: she had tripped on a loose carpet on her stairs at the House Beautiful and had tumbled to the bottom, seriously injuring her spine.

It was hubris which caused Oscar to stay and face trial, believing his wit and charm would sway the jury. When asked by the prosecution if he had kissed a certain boy, Oscar answered with his celebratory wit, “Oh, dear, no. He was unfortunately extremely ugly.” While Constance’s former rival Florence’s husband was lauded as the author of Dracula, Constance’s own husband was now viewed as the real thing.

The result was Wilde not only lost his suit against Queensbury but was in turn tried and convicted for “acts of gross indecency” (homosexuality). He was sentenced to two years of hard labor at Reading Prison. Constance’s voiced her compassion, “He is such a poor, poor fellow. What a tragedy for him who is so gifted.” Post-trial, the once enviable life of Constance became akin to the Walls of Jericho: the egg thrown on her husband landed on her. The trial had drained their financial resources, her two sons were targets of bullying, and she could only walk with great difficulty. Constance, along with her husband, was equally victimized by the hypocrisy of Victorian society.

Her brother Otho, once again a lifesaver, arranged for her to leave England and relocate to the Continent where she changed her surname to Holland, a family name which was also Otho’s middle one. Nevertheless, she did not seek a divorce; although she had married the wrong man she loved him just the same. In addition, though she dreaded returning to England, she did so to deliver the heart-breaking news to her husband that his beloved mother had passed away. She could not wrap her arms around Oscar as she was separated from him by bars which forced them to remain three feet apart. During the brief time permitted, he poured out his grief to his wife for the pain of losing his mother and his hatred of his nonfictional Dorian Gray ( Bosie) who he swore he would kill if he saw again. He related how someone had spat in his face and how, each day at the same hour, he wept, remembering the indignity. Post -visit she poured out her own grief in a letter to her friend, “He is very repentant and minds most of all what he has brought on myself and the boys. It seems to me that by sticking to him now, I may save him from even worse.”

When Oscar, broken in body and spirit from his incarceration, was released, Constance informed him she would provide an annual stipend from her trust fund and invited her prodigal husband to rejoin his family in Genoa. He was making plans to do so when he instead decided to meet up with Bosie (who Constance referred to as ‘that appalling individual,’) in Naples. Preferring his Judas to his wife led even Constance to her breaking point; she declared Oscar was “weak as water,” and at long last, the marriage of the Wildes’ ended sadly, madly, badly. Oscar lost his parental rights; he was never to see wife or sons again. But again, even though their marriage ended their love never did. In her last letter Constance wrote to Otho of Oscar’s final literary work, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” “I was frightfully upset by this wonderful poem…it is tragic and makes one cry.” Its line which carried the most personal resonance , “Each man kills the thing he loves.”

Constance underwent an operation and passed away on April 7th, 1898, with only a nurse in attendance. She was interred in the Campo Santo Cemetery in Genoa. The following year Oscar visited her grave site and broke down in tears. He wrote to his friend Ross, “It was very tragic seeing her name carved on a tomb-her surname, my name, not mentioned. I had a sense of the uselessness of all regrets. Life is a very terrible thing.” In 1963 her family added an addendum to her tombstone: wife of Oscar Wilde.

After life with her flamboyant and tortured genius, Constance deserves to recline and remember the time before Oscar wore his variation of Hester’s scarlet letter.