Love Trumped Haight (1892)

In Dr. Seuss’ first book, Marco observes a horse- drawn cart that he imagines into a zebra- drawn chariot. The story’s refrain, “And that is a story that no one can beat/When I say that I saw it on Mulberry Street.” Had Marco experienced San Francisco’s infamous thoroughfare he would not have needed to resort to fantasy. The intersection of Haight and Ashbury is world- famous though its allusion-to Henry Huntly Haight- has receded into historical amnesia.

Place names are evocative of history: London’s Abbey Road of the Beatles’ crossing, Paris’ Avenue des Champs-Élysées of the iconic Arc de Triomphe, Jerusalem’s Via Dolorosa of Christ’s final walk. And “the Haight” is entrenched with the spirit of the 1960s counterculture though its namesake was far from its spirit of brotherhood.

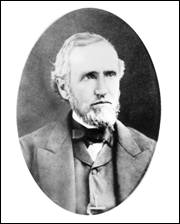

The bearer of the triple alliterative name, Henry Huntly Hunt, was born in Rochester, New York, in 1867. After graduating from Yale University, he joined his father, Fletcher Matthews Haight, law firm. The lure of the Gold Rush proved an irresistible draw and in 1849 Henry departed for San Francisco. In the west, Henry mined the world of politics and led Abraham Lincoln’s campaign for presidency, a decision he later regretted. As the tenth governor of California, Henry claimed that Congress’s policy put white Americans “under the heel of negroes” He referred to Asians as a “servile, effeminate and inferior race” and claimed giving them the vote desecrated the democratic heritage. On a more uplifting note, his tenure oversaw the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the establishment of the Golden Gate Park, the founding of the University of California. In tribute, Ordinance No.189 named Haight Avenue after their governor. Henry’s wife, Anna, praised him, “Truly him was a tree that bore good fruit.”

Haight and Ashbury were the Mecca of the hippie counterculture, lightyears away from the violence of Vietnam. The neighborhood shimmered with psychedelic colors, drugs, and rock music. The Haight (as the locals call the neighborhood) was the oasis for the dropped-out generation where marijuana fumes mingled with the scent of burning draft cards, where “make love not war” signs proliferated. In that Summer of Love 100,000 people converged to overthrow the establishment, to voice their solidarity with the Civil Rights Movement. The dramatics persona were musicians: the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin; record stores sold their records as well as hallucinogens. The balladeers were Allen Ginsburg, Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady. Timothy Leary, the ex-Harvard professor turned LSD guru, preached the gospel of drugs. Resident Hunter S. Thompson christened Haight ‘Hashbury.’ Amongst the flower power generation, the area also housed the psychopath, Charles Manson, and the Hells Angels.

The era provided high times until the day the music died. The Haight, as the case with its once youthful pilgrims, succumbed to the effects of age. Overcrowding, homelessness, crime, and drug addiction took its toll. Eventually, the altar of consumerism sacrificed youthful idealism. While Scott McKenzie had sung, “When you come to San Francisco/Be sure to wear flowers in your hair,” tourists now need to bring credit cards. The arrival of the tech titans brought gentrification; free love now equates with Tinder; “the sound of “ka-ching” has dethroned the blues. In 2022, a three-bedroom, two bath condo on Haight Street sold for $2,600,000-far-out of reach for its former denizens.

At the legendary crossroad is a two-faced clock, hands frozen at 4:20, a wink to weed. The timepiece is a fitting metaphor for an era when love trumped “haight.”