Hike! (1936)

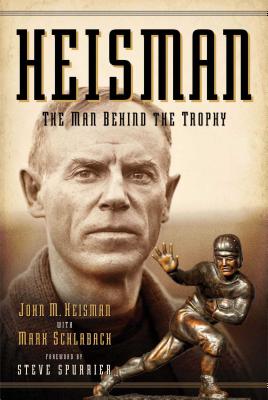

The poet, A. E. Housman wrote, “In the spring a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love.” In the world of football, a young man’s fancy turns to thoughts of the Heisman Trophy, the most prestigious in college sports. But what even the most fanatic of fans may not know is the namesake of the award: Coach John Heisman, (nicknamed Doc.)

The iconic prize could have been christened the von Bogart Trophy. The German Baron von Bogart disinherited his son, Michael, for marrying Sarah Lehr Heissman, a lower-class girl from Alsace-Lorraine. To distance himself from his father, the couple moved to America where they settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where Michael adopted his wife’s maiden name, minus an ‘s.’ Their son, Johann, (John,) Wilhelm was born in 1869, two weeks before the first American foot game took place between Princeton and Rutgers in New Jersey. (Currently, his childhood home is a designated historical landmark.) At Brown University, John played football and baseball before he transferred to the University of Pennsylvania. During a game at Madison Square Gardens, the stadium’s antiquated battery lights damaged his eyes that resulted in him changing his career path from law to sports. He became a coaching Johnny Appleseed who took positions in Ohio, Alabama, South Carolina, Texas, and Georgia. Using his experience as an actor in Shakespearean summer stock plays, he delivered melodramatic locker-room oratory, “Better to have died as a small boy than to fumble this football.” In 1903, John married fellow thespian, Evelyn McCollum Cox; the marriage ended in divorce. He oversaw the greatest victory in the history of sport: Georgia Tech 222, Cumberland 0. He benched players for poor grades, and at times left practice early to attend the opera. Professors were infuriated that his $9,000 annual salary surpassed their own. The coach wore his sport on his face: he had a flattened nose he received in 1890 while blocking a punt against Penn State.

In 1922, John wrote Principles of Coaching where he wrote that a coach should be “little short of a czar,” admit his mistakes, and never use profanity. In a chapter on healthy training, John railed against smoking and coffee during the season, and alcohol at any time. Ice cream was fine, though not more than a few times a week, a dessert he felt to his poodle, Woo. Heisman served as the game’s conscience; when coaching Washington & Jefferson in 1923, he refused to play a game when the Virginia school demanded that a black player be removed. At Georgia Tech, he counselled a Jewish player who had been a victim of anti-Semitism. One of his many innovations was the erection of a scoreboard.

After a thirty-six-year coaching career, John and his second wife, Edith retired to Manhattan where he owned a sporting goods company. The newly opened Downtown Athletic Club recruited him as its director where, five years later, it came up with the idea of granting an annual reward for the best college football player. The DAC wanted to name its trophy after John, an honor he declined as he felt it wrong to honor a single player in a team game. The first recipient was Jay Berwanger, a halfback who played on the same university of Chicago site where physicist Enrico Fermi later split atoms in the race to create the hydrogen bomb.

After a thirty-six-year coaching career, John and his second wife, Edith retired to Manhattan where he owned a sporting goods company. The newly opened Downtown Athletic Club recruited him as its director where, five years later, it came up with the idea of granting an annual reward for the best college football player. The DAC wanted to name its trophy after John, an honor he declined as he felt it wrong to honor a single player in a team game. The first recipient was Jay Berwanger, a halfback who played on the same university of Chicago site where physicist Enrico Fermi later split atoms in the race to create the hydrogen bomb.

A few days before his 67th birthday, John passed away from pneumonia. The Yankee defeat of the Giants in their first World Series with Joe DiMaggio overshadowed the coach’s passing. His internment was the Forest Home Cemetery in Rhinelander, Wisconsin, his wife’s hometown. Two months later, the DAC renamed the award after the trailblazer.

The sexton said few come to pay tribute. However, for those with a superstitious bent, on the date of the December award ceremony, the ghosts of his former players surround his grave, and call out the signal their coach instituted, “HIKE!”