Called Home

“The Riddle we can guess/We speedily despise-” Emily Dickinson

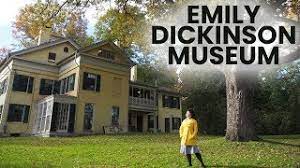

The Emily Dickinson Museum (opened in 2003)

280 Main Street, Amherst, Massachusetts

“Because I could not stop for Death-He kindly stopped for me-The Carriage held but just Ourselves-And Immortality.” Emily’s immortality rests on her poetry, her legacy enshrined by The Emily Dickinson Museum.

The reclusive woman in white is as interwoven with The Homestead in Amherst as Emily Bronte was with the Bronte Parsonage in Haworth. The yellow brick house was where Emily was born in 1830, wrote her poetry, and died in 1886. While many can relate interesting family stories, few can claim theirs established a university. The poet’s grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, founded Amherst College; in 1813, he built the Homestead on Main Street. Her father, Edward, was a Calvinist lawyer and politician who gave his family material comforts yet proved stingy with affection. His daughter Emily confessed, “I am not very well acquainted with father.” Before marriage, he warned his fiancée, “I do not expect or wish for a life of pleasure.” What counteracted emotionally frigid parents was Emily’s bond with older brother, Austin, and younger sister, Lavinia. In her youth, Emily entertained a vision of her future, “I am growing handsome very fast indeed! I expect I shall be the belle of Amherst when I reach my 17th year. I don’t doubt that I will have crowds of admirers at that age.” Although she never wed, evidence shows George H. Gould, a graduate of Amherst College, proposed.

At age seventeen, Emily spent a year-the longest she was ever away from the place she always referred to as “her father’s house-” at Holyoke Female Seminary, later Mount Holyoke College. As a student, she formed strong female friendships, though her unconventionality caused administrative pursing of lips. When headmistress Mary Lyon pressured her students to be “saved” everyone acquiesced- except for Ms. Dickinson. Miss Lyons consigned her wayward pupil to the lowest of three categories- “the saved, the hopeful and the no hopers.” The “no hoper” wrote, “Faith” is a fine invention/When Gentlemen can see-But microscopes are prudent/In an Emergency.” English teacher, Margaret Mann’s, assessment, “She was somebody who walked on the diagonal while everybody else was keeping to the square.” Letters to her brother reveal Emily’s mounting sense of alienation, “What makes a few of us so different from others? It’s a question I often ask myself.”

Although she had written poetry in college, the portrait of the artist as a young woman took shape during the Civil War. (Austin paid for his replacement in the army). Her disgust with the conflict is hinted at in her lines, “How martial is this place! /had I a mighty gun/ I think I’d shoot the human race/And then to glory run!” By age thirty-five, Emily had penned more than 1,100 lyrics that plumed the depths of grief, pain, love, nature, art, and death. She recorded 800 of her works in small, handmade booklets (fascicles) mostly earmarked for her eyes only. Considering publication, however, she contacted Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an advocate for abolition and women’s rights. He rejected her poems with the pronouncement they were too odd. He visited her twice in the early 1970s and reported to his wife, “I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much.”

Unlike their strait-laced parents, the Dickinson siblings were creatures of emotion rather than models of Puritan propriety. Lavinia was so hell-bent on marrying Yale student Joseph Lyman that she coiled her long hair around his neck. He resisted being reeled in and retreated to New Orleans. Her low-cut dresses distressed Edward who snapped, “Lavinia, put on a shawl!” Austin proposed to Susan Huntington, (Emily’s long-time friend,) who was loath to accept. He then offered a “mariage blanc”-a union devoid of sexual intimacy. After she became Mrs. Dickinson, the couple resided in The Evergreens, an Italianate mansion, a wedding present from Edward, separated by hedges from The Homestead. Emily doted on their children, Ned, Martha, and Gilbert. An eminent visitor to The Evergreens was Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Misgivings over marrying Austin may have stemmed from Susan was beloved by both brother and sister. At age twenty, Emily longed to hold her “in my arms.” In a letter to Susan, (who she addressed in correspondence as “Darling Sue,”) she wrote, “Susan knows/she is a Siren-/and that at a/word from her, /Emily would/forfeit Righteousness-.” Correspondence with Susan outnumbered those with anyone else. Regardless of the nature of their relationship, Susan served as Emily’s “primary reader,” influenced her literary output, and claimed they merited publication. Near the end of her life, Emily acknowledged Susan’s influence, “With the Exception of Shakespeare, you have told me of more knowledge than any one living-To say that sincerely is strange praise-”

At age twenty-three, Emily began to retreat into her Homestead shell as evidenced when she declined an invitation from her friend, “I’m so old-fashioned, Darling, that all your friends would stare.” By age forty, communication was through partially closed doors, and her “attendance” at family events was observance from the top of the stairs. When she needed a new dress, the seamstress fitted it on Lavinia. During illness, her doctor made a diagnosis as he walked past her door. Her reclusiveness may have been a shield against a society that wanted her to conform to the roles of wife and mother. Domesticity held little appeal, “House is being cleaned. I prefer pestilence.” Expressing her desire to divest herself from the outside world she wrote, “The Soul selects her own Society-Than-shuts the Door-” The town took to referring to the mysterious recluse-who dressed only in white after her father’s passing- as “The Myth.”

The affair that greatly impacted her later life was not her own. Amor in Amherst ignited in 1881 when the fifty-four-year-old Austin fell in love with the twenty-six-year-old Mabel, the wife of David Peck Todd, an assistant professor of astronomy at Amherst College. (The twenty-year-old Ned was the first to fall for her charms.) Austin noted the event in his diary with one word: Rubicon. David was compliant with his wife’s adultery as he also side-stepped his marital vows. The wife scorned fury never abated. The couple’s assignation was the Homestead where Austin and Mabel made love on its dining-room horsehair sofa. The woman in white was upset with the affair that caused Susan pain, and made Austin, a pillar of Amherst society, the object of gossip. Emily referred to Mabel as the “Lady Macbeth of Amherst.” The affair lasted until Austin’s death thirteen years later. Another source of grief was she had to commit Todd to a mental institution due to his increasingly erratic behavior.

At age fifty-six, the poet who “dwelt in possibility” passed away, ostensibly from Bright’s Disease. Susan dressed Emily in white satin and penned her obituary. After her sister’s internment, Lavinia discovered roughly 1,100 poems locked in a chest of drawers. She asked Susan to help with the publication of Emily’s poems; frustrated with her slow progress, she turned the task over to Mabel.

Emily’s spirit hovers in The Homestead where thousands of fans undergo a sacred pilgrimage. The downstairs library displays copies of The Springfield Daily Republican that published Dickinson poems anonymously in her lifetime; the newspapers sit on a table as if she had just put them down. Throughout the rooms are fragments of verse penned on envelopes, scraps of paper, and candy wrappers. The only incongruent element is the museum placed pinecones on chairs to discourage unwelcome seating.

Emily’s bedroom bears rose-patterned wallpaper, a Franklin stove, and a cradle-an odd addition in a spinster’s space. A plexiglass case displays a headless dressmaker’s dummy draped in a facsimile of one of Emily’s white dresses, seemingly a size eight. Across her sleigh bed is a brightly patterned shawl. A reproduction of her writing desk, (the original resides in Harvard,) conjures Amherst’s writer, quill in hand. On the windowsill is a basket with an attached cord that Emily filled with baked goods and lowered to her nephews and niece. The tour concludes with visitors descending the stairs that leads to the back door through which Emily at last left The Homestead in her white coffin headed for burial in the nearby West Cemetery. The inscription on her gravestone consists of her own words: “Called back.”

A View from Her Window:

The windows of The Homestead provided Emily a glimpse of a world from which she had retreated. Through the glass panes she could see the town’s main thoroughfare that led to Boston, a road used for funeral processions on their way to Amherst’s cemetery. Glimpses of nature infused her poetry, “A Drop fell on the Apple Tree-Another-on the Roof-A Half a Dozen kissed the Eaves-And made the Gables laugh-”

NEARBY ATTRACTION: The Boston Tea Party Ships and Museums

Visitors can stand on a ship and enact the historical event when the colonists threw tyranny and tea into the Boston Harbor. After departing the vessel, guests enter the Tea party museum where they can view the Robinson Half Chest, one of only two known tea chests still in existence from the event that marks the protest that helped fuel the American Revolution.