Till I Die (1847)

John Muir, the naturalist who was most at home sleeping outdoors on a bed of pine needles, called the sequoias the “noblest of God’s trees.” The wooden sentries were in their infancy when the Coliseum hosted its gladiator games; their tallest branches would dwarf Lady Liberty’s crown. The spiritual groundskeeper of the Sierra Nevada’s sacred forest: Sequoyah.

Ironically, the trees that bear the name of a Native American from the East never laid eyes on nature’s superlative. Sequoya was born in 1760, present day Tennessee, the son of Nathaniel Gist, a white commissioned officer in the Continental Army. General George Washington sent Gist to the Cherokees to recruit men to fight the British. In this capacity Gist met Wurteh, a sister of Old Tassei, the head chief of the Cherokee nation. Gist never acknowledged his son and Wurteh raised him on her own. Either because of a birth defect or subsequent injury, his tribe referred to him as Sequoyah, which translates to “pig’s foot.” Despite his mixed heritage, Sequoyah faithfully clung to his tribe’s clothes, religion, and language.

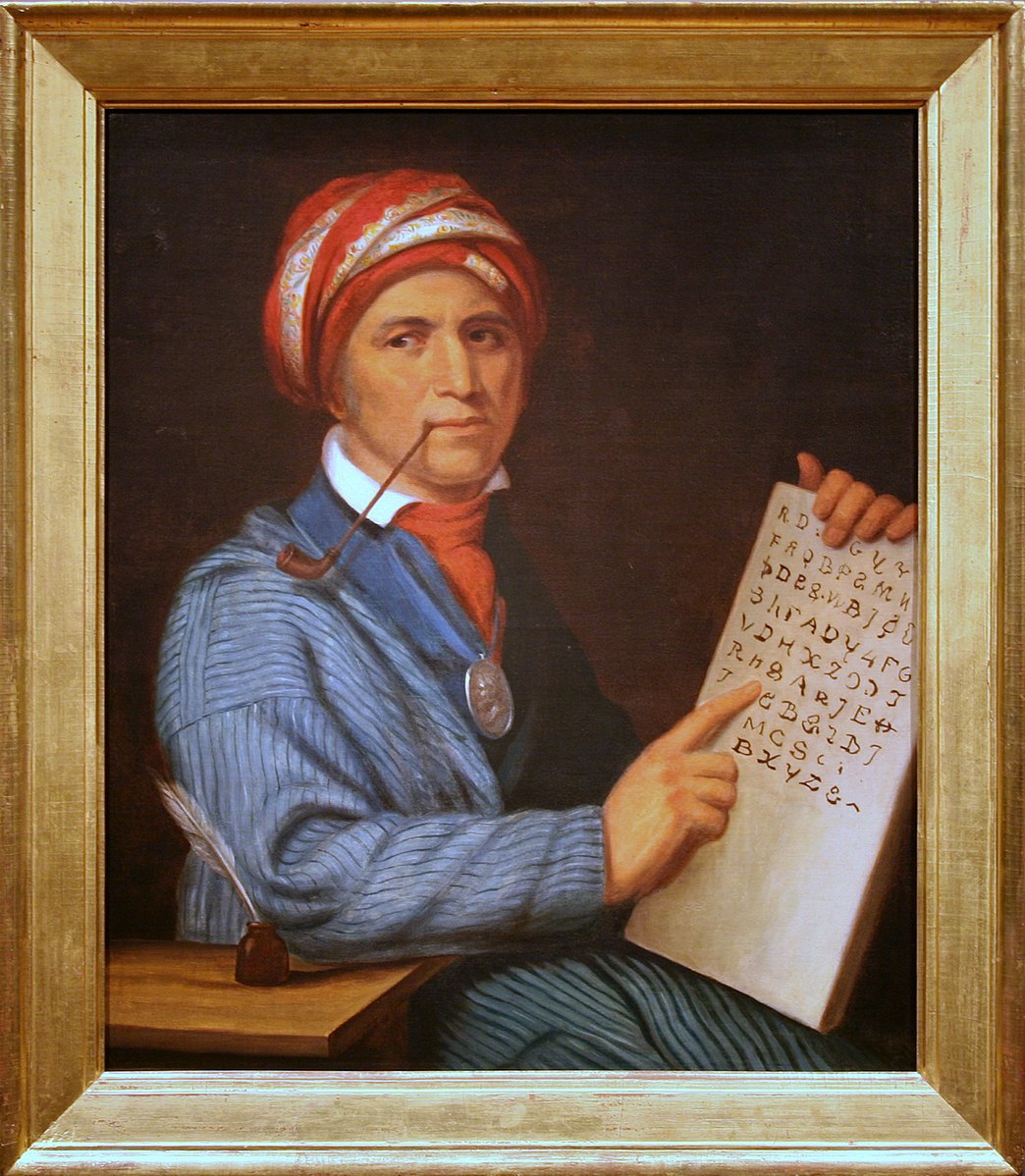

Fiercely against assimilation, Sequoyah nevertheless admired the white people’s practice of “talking leaves,” what the Native Americans referred to as written language, something foreign to Cherokee culture. Although Sequoyah had no knowledge of reading or writing, he felt that the betterment of his people lay in unlocking the secret of ink-stained markings on paper. He said of his challenge, “The white man is no magician.” For twelve years he labored to create an alphabet that would allow his people to preserve their past, communicate with exiled tribal members, and serve as an organizational tool. His fellow tribesmen-as well as his wife-felt he was practicing black magic that would tempt the wrath of the gods. Undaunted, Sequoyah taught his system to his six-year-old daughter, Ayokeh.

Brought to trial before a chief, Sequoyah communicated with Ayokeh through his invention. Sensing the tool’s potency, the chief ordered that the system be spread throughout his nation. Within a few years, the Cherokee became adept in the new art and enjoyed widespread literacy. In 1828, The Cherokee Phoenix became the first Native American newspaper in the United States.

In the 1852, Augustus T. Dowd, a hunter in charge of supplying food to the Gold Rush miners, chased a wounded bear into the woods and stumbled upon trees that seemed to belong in the garden of a giant. Men cut down a tree and after counting the rings, a newspaper reporter declared, “It must have been a little plant when Samson was slaying the Philistines.” The news spread rapidly, and the area transformed into a tourist attraction. A leading British botanist proposed the superlative species bear the name Wellingtonia gigantea in honor of the Duke of Wellington who had defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. However, the final christening lay with Stephan L. Endlicher, a renowned 19th century botanist who served as the curator of the Vienna Museum of Natural History. He dubbed the recently discovered genus of giant Californian trees Sequoiadendron Giganteum after the Native American creator of the Cherokee writing system. Endlicher ended up a victim of suicide; however, his namesake lives on in nonpareil splendor.

In 1842, Sequayah left his log cabin at Skin Bayou to locate a lost band of Cherokee. He reconnected with them in Northern Mexico where he died a year later from natural causes. His son laid him to rest in a nearby cave. In 1971, the Raiders released a song that could well have come from the mouth of Sequoyah, “They took the whole Indian nation/Locked us on a reservation/Though I wear a shirt and tie/I’m still part redman till I die.”