Of Their Number

“Afflictions are the steps to heaven.”

–Mother Elizabeth Ann Seton

The National Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton (opened 1965)

Emmitsburg, Maryland

A Negro spiritual, popularized by Louis Armstrong, begins with the lyrics, “Oh, when the saints go marching in, oh, when the saints go marching in…” To learn about the woman who traversed the road from socialite to saint, head to Emmitsburg, Maryland, the site of the National Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton.

In 2015, when Pope Francis visited America, he transformed to a septuagenarian superstar. Time placed the Bishop of Rome on its cover thereby beating out Syrian President Bashar-al-Assad, whistle blower Edward Snowden, pop star Miley Cyrus. Popemania illustrated how far the United States had come from its historic roots where Protestantism ruled the roost. In 1960, John F. Kennedy made his plea, “I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democrat’s Party’s candidate for president, who happens to be a Catholic.” Anti-Roman Catholicism was a cross Mother Seton bore.

Born into the colony of New York in 1774, Elizabeth Ann was the second daughter of Catherine and Dr. Richard Bayley, socially prominent Episcopalians. Dr. Bayley served as New York’s first public health official, as well as the first professor of anatomy at King’s College, currently Columbia University. When Elizabeth was two years old, Catherine died giving birth to Kit who passed away a year later. Dr. Bayley’s second wife, Amelia Charlotte Barclay, was a granddaughter of Jacobus Roosevelt, founder of the Hyde Park branch of the political dynasty. Maria and Elizabeth never warmed up to their stepmother who they addressed as Mrs. Bayley. To ease family tensions, Richard sent his two eldest children to live with their Uncle William and Aunt Sarah in New Rochelle, a city the girls’ forbears had founded. An indelible childhood memory for the fourteen-year-old Elizabeth was standing on Wall Street amidst the celebration for George Washington’s appointment as the nation’s first president.

When Elizabeth met William Magee, heir to a Manhattan mercantile fortune–he called her Eliza, and, like Eliza Doolittle, she could have danced all night. Nineteen-year-old Elizabeth married William in the social event of the 1794 season officiated by the Right Reverend Samuel Provost, the first Protestant Episcopal Bishop of New York. The bride’s adornment was a family keepsake, a gold filigree brooch. The Setons moved into a Wall Street house where their neighbors were Alexander and Elizabeth Hamilton. The Setons’ residence echoed to the strains of Elizabeth’s piano and William’s violin that he had purchased in Cremona, Italy, the first known Stradivarius in America. The instrument remained an heirloom until a grandson left it on a train. In pride of place was a silver tea set that bore the image of a fire-breathing dragon and the motto, “At Whatever Risk, Yet Go Forward.” In 1797, William, in powdered wig and brocade coat, hosted a ball for President Washington’s sixty-fifth birthday. His wife wore cream satin, monogrammed shoes. Guests included Roosevelts, Hamiltons, and Astors.

Life was wonderful until the Setons encountered the period of “these are the times that try men’s souls.” By 1800, William’s shipping business went bankrupt due to piracy and conflict in Europe. The Setons lost their home and most of their valuables. The financial blow was made more dire considering William was supporting his immediate family as well as his six younger stepsiblings. Further heartbreak followed: Dr. Bayley passed away from yellow fever; William came down with tuberculosis.

Praying Italy’s warmer climate would provide a cure, William and Elizabeth set sail on The Shepherdess to Leghorn, Pisa, with their oldest daughter Anna. Officials assumed William suffered from yellow fever and ordered the family into the lazaretto, a dungeon-like quarantine center. William passed away in 1803, age thirty-five; his widow arranged his burial in the graveyard at St. John’s Anglican Church. Elizabeth dressed in traditional Italian widow’s garb–a black dress with a ruffled cap–that she wore all the days of her life. While waiting for a return passage, mother and daughter stayed with Antonio and Amabilia Filicchi with whom they toured Florence. Visiting the city’s ancient churches, Elizabeth underwent the epiphany: Roman Catholicism “was the one, true Church.”

While Elizabeth’s conscience was at peace with her decision, her circle was incensed. A Quaker friend, assuming she only sought a change, told her, “Betsey, I tell thee, thee had better come with us.” Elizabeth received the sacrament of Confirmation from the Bishop of Baltimore, the Right Reverend John Carroll-the only Catholic bishop in the country. She wrote to Amabilia, “God is mine and I am all His.”

After a year in Baltimore–as Maryland was the state most receptive to Catholics–in a covered wagon, Elizabeth travelled to Emmitsburg, ten miles south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Home was a residence she and her sisters dubbed Stone House–that was stone cold as drifts of snow entered from the decrepit structure. Sixteen women slept in four rooms. Her next residence, dubbed the White House, provided far better accommodation. In Emmitsburg, Elizabeth founded St. Joseph’s, America’s first Catholic school. She also established the first American order of nuns, the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s. Elizabeth was devastated at the loss of two daughters from tuberculosis: Anna, at age sixteen, Rebecca, at age fourteen. She interred them under the oaks in a cemetery she christened God’s Little Acre.

Intrepid to the end, in 1821, as Elizabeth lay dying from the dreaded disease that had stalked her family, she wrote her friend, “I see Death grinning in the pot every morning…and I grin back.” Her passing saved her from her son Richard’s death at sea, two years later.

A century and a half after Elizabeth’s death, Pope Paul VI announced the canonization of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton. Among the 100,000 onlookers were Carl Kalin and Ann O’Neil Hooe, both who had recovered from life-threatening illnesses after prayers to Mother Seton. The church deemed their cures as miracles. Post ceremony, the words “American saint” were no longer an oxymoron. Another first was the Sistine choir included Americans such as members of the Emmitsburg Community Chorus. The seventy-seven-year-old Pope spoke “ex cathedra” which means “from the chair” who proclaimed in English that Blessed Elizabeth Ann Seton to be Saint Elizabeth Ann, forever afterwards to be hailed as “a citizen of Heaven and worthy of veneration by the Universal Church.” The ceremony took place against the backdrop of the world’s largest church that displayed a six-yard-long tapestry of Saint Seton in her black habit, standing on a cloud over a globe with North American bathed in sunlight. The canonization represented a century of effort by American Catholics who had lobbied for Elizabeth’s sainthood. After her beautification, Catholic Churches could display her statue, could bear her name, both of which transpired in the National Shrine of Elizabeth Ann Seton.

When visiting the museum-shrine, on its grounds lies Elizabeth’s Stone House whose period furnishings transport one back to the early 1800s. In 2015, President Barack Obama presented Pope Francis with the original key to Elizabeth’s first Emmitsburg home. The White House holds a piano, the room where Elizabeth taught French and catechism. A room still displays students’ slates, maps, and rows of little chairs. In the roped-off corner is the area where Elizabeth passed away.

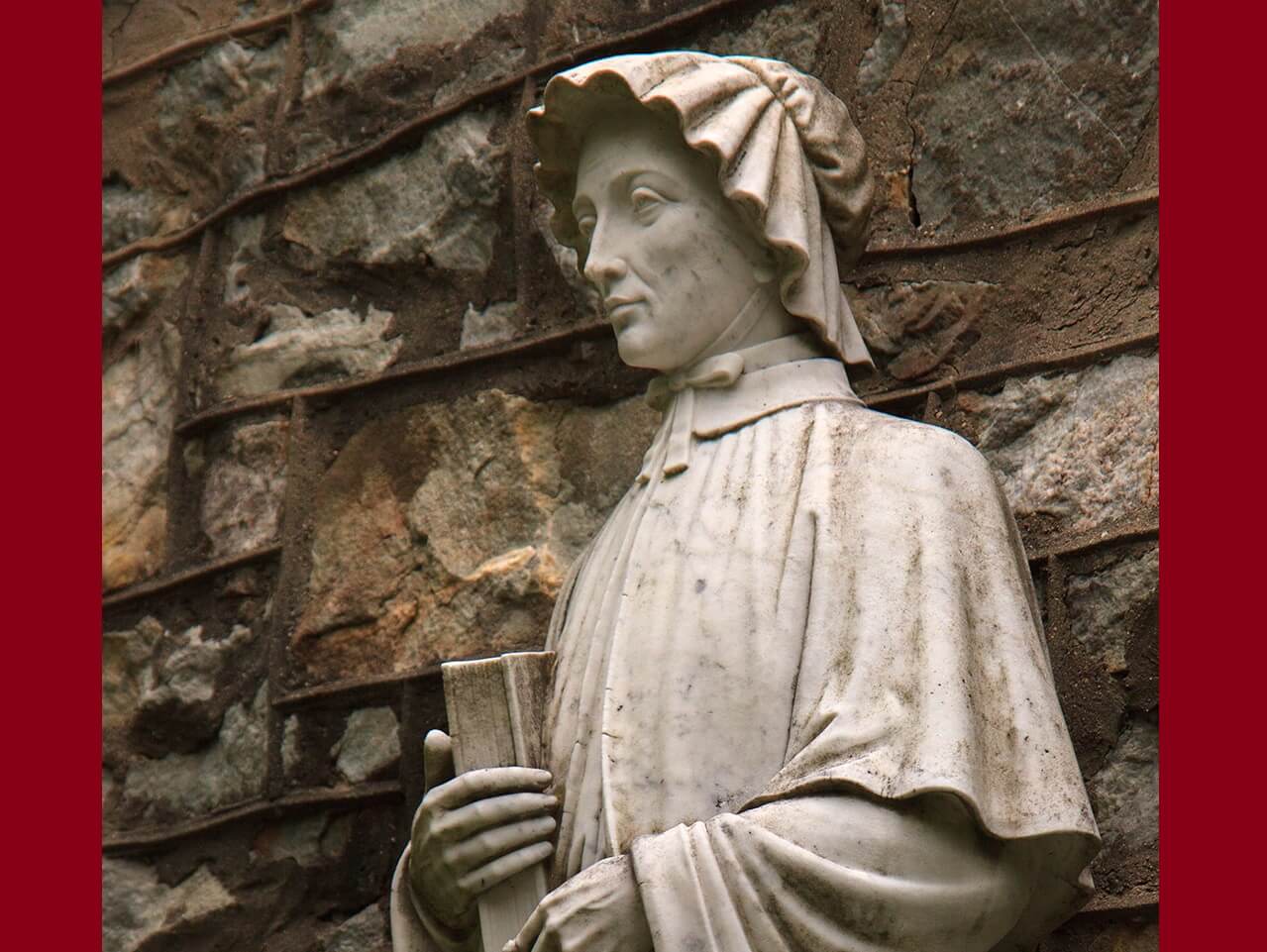

The Seton Shrine Museum, refurbished for $4,000,000, is a structure of marble and mosaics, stained glass windows and cathedral ceilings. The vestibule features an enormous painting of St. Seton floating above the Earth, as well as her white statue that had originated in Italy. The Basilica, with its monumental dome, includes the Altar of Relics where the patron saint’s remains rest in a copper casket.

Through her personal belongings, Elizabeth is resurrected. The museum houses her collection of leather and gold-covered books, as well as the “little red book” that served as a message of motherly wisdom to Catherine. Sentimental objects are the hand-painted wedding porcelain miniatures that depict Elizabeth and her husband. On the back of her portrait lies strands of her hair; the back of her husband’s displays his initials. Another bridal memento is her gold filigree bridal brooch and cream-colored shoes. Elizabeth’s black cap with ruffled frill is especially moving. Other family mementoes are Catherine’s christening gown, locks from her daughters’ hair, her father’s tea chest–that still holds enough for a cuppa or two–and photo albums. The religious relics of yesteryear: her black glass bead rosary and crucifix that bears skull and crossbones. For over two centuries, a large woodcarving featuring the scene from Cavalry hung over the fireplace on the White House wall. The artifact is now in the Servant Gallery of the National Shrine, likely a gift from the Filicchi family.

For a life of selfless devotion, when the saints went marching in to heaven, Mother Seton was of their number.

The View from Her Window: If Mother Seton could have gazed from Stone House to the National Shrine of Elizabeth Ann Seton, the New Testament quotation could have come to mind, “God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform.”