Nevermore

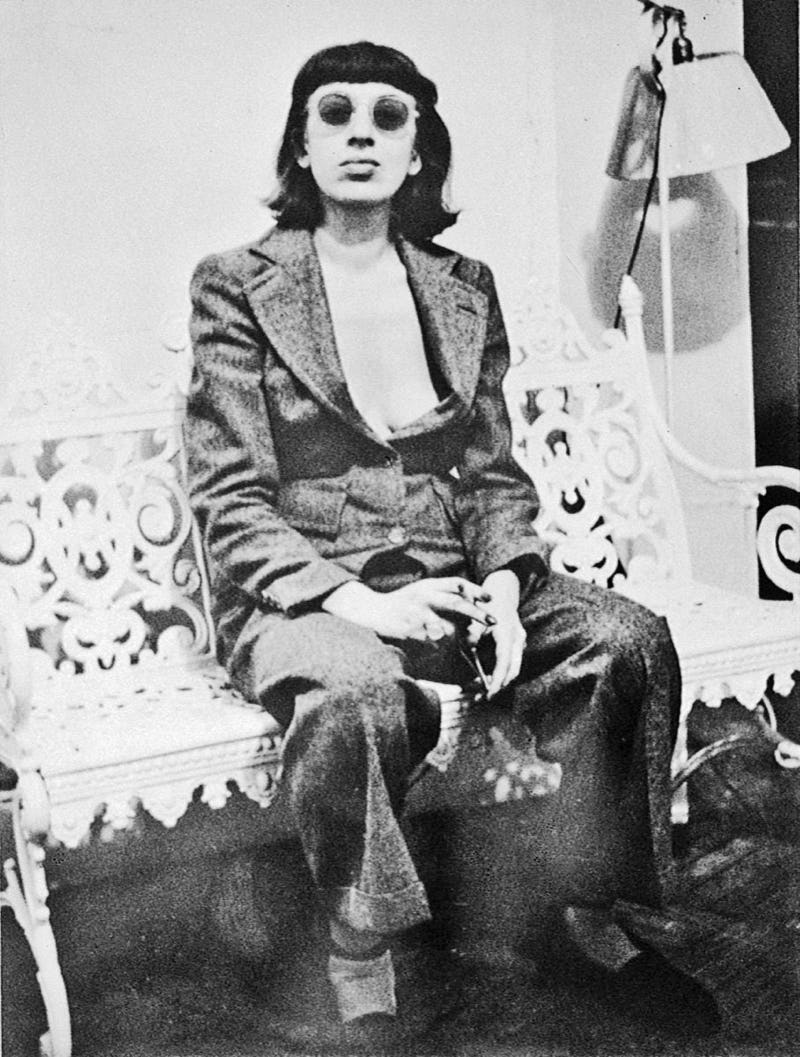

Lee Krasner

“I don’t feel I sacrificed myself.”—Lee Krasner

The Pollock-Krasner House (opened 1988)

A well-known trope postulates, “Behind every great man is a great woman.” History tends to forget these ladies, as great men can be reluctant to provide spousal credit. Ultimately, the artist formerly known as Mrs. Pollock became Lee Krasner. To experience Lee’s paint-bedecked studio, follow the turpentine fumes to The Pollock-Krasner House.

If anyone did not seem destined to make her mark in the avant-garde art world, it was the Brooklyn-born Lena Krasner, one of seven children. Her parents were Orthodox Jews from a Russian shtetl who had fled after the 1903 Kishinev pogrom. She changed her name from Lena to Lenore because of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven,” which portrays a man tormented by the loss of his beloved. Poe described the man’s angst: “Vainly I had sought to borrow / From my books surcease of sorrow-sorrow for the lost Lenore”. The rebel settled on the American, androgynous Lee, and removed an ‘s’ from her surname. Family drama transpired when Rose, her older sister, died, leaving her husband, William Stein, and two young daughters. In keeping with Jewish tradition, as the next oldest daughter, her parents expected Lee to marry William, a movie-projector operator. Upon her refusal, the responsibly fell to her sixteen-year-old sister, Ruth. As a result, the siblings’ relationship suffered.

The Girls High School expelled Lee for refusing to sing religious Christmas carols, something she objected to as a Jew. At age thirteen, Lee attended Washington Irving High, the only school in New York to permit females in art classes. Postgraduation, she enrolled in the National Academy of Design which she described as a place of “congealed mediocrity.” During the Great Depression, Lee painted murals for the WPA artists’ project where she met Willem de Kooning. A scholarship allowed her to study with Hans Hofmann, a German émigré abstract expressionist painter who had known Matisse, Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Picasso. He commented on her canvas, “This is so good, you would never know it was done by a woman.” Until he ended the relationship, Lee lived with a Russian art student, Igor Pantuhoff.

In 1940 Manhattan’s McMillen Gallery was putting on an exhibit featuring Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Georges Braque, and invited an equal number of unknown American artists: Willem de Kooning, Paul Jackson Pollock, and Lee Krasner. As Jackson lived a block away, Lee dropped by, although Willem had described Jackson as looking like “some guy who works at a service station pumping gas.” She recognized him as the man she had met four years earlier at an Artists’ Union loft party and had refused to go out with him because he was a “lousy dancer.” Then she saw his paintings and recalled, “I almost died.” Falling for the artist as well as his art, lousy dancing no longer mattered. Lee moved in.

Weeks after V-J Day, after they were married in Marbel Collegiate Church in Manhattan, they visited Springs, East Hampton, Long Island, and swooned under its spell. For five thousand dollars they purchased a nineteenth-century farmhouse on the Accabonac Creek, replete with a barn and five acres. Heiress Peggy Guggenheim provided the two thousand-dollar down payment; she adored Jackson, though she never cared for Lee. Peggy was equipped with a sex drive as huge as a Pollock canvass. She tried to seduce Jackson, but he later remarked, “You would have to put a towel over Peggy Guggenheim’s head to have sex with her.” Other men were not as discerning. When asked by an interviewer how many husbands she had, Peggy replied, “Mine or other people’s?” The home lacked heat, hot water, and an indoor bathroom, but it provided—if not Poe’s raven—a crow they named Caw-Caw. In their isolated sanctuary, the couple dug for clams, rode their bikes to the beach (they did not own a car), and painted. A Hampton Mother Hubbard, Jackson traded art for food with the proprietor of the nearby Springs General Store; it displays a reproduction of the Pollock painting that the store obtained in the deal of deals. Local lore holds that the Jackson Pollock canvass sat behind the couch of the store’s owner for years as he did not know what to make of the paint-splashed painting. Lee harbored the hope their rural retreat would distance her husband from the siren call of the Greenwich Village bars. As the first of the post–World War II artists to settle in the Hamptons, the Pollocks were the founders of its legendary art colony.

Initially Jackson painted in their bedroom; however, requiring more space, he turned their barn into his studio whose open space allowed him to lay a giant canvas on the floor, resulting in his breakthrough “drip method.” Life magazine declared Pollock was the greatest living artist in the U.S. During their hungry days, they would have been astounded that a Lee Krasner painting would be sold for $11.6 million, a Jackson Pollock for $200 million.

The paradigm in their marriage was while he was the one with the fame, she was the watchdog of his reputation. She recalled, “There were the artists and then there were the ‘dames.’ I was considered a ‘dame’ even if I was a painter too.”

As Jackson’s success skyrocketed, he proved he was not only adept with his paintbrush. When Lee learned of her husband’s infidelity, she again, though in a different way—felt “I wanted to die.” While intoxicated, he could also make her the target of his verbal grenades: “Imagine being married to that face.” Deeply hurt at his cruelty, womanizing, and drinking, Lee commuted to Manhattan to consult with her psychiatrist. Still, she sacrificed at his alter and only denied him a child. As she explained, she “married him to become an artist, not a mother.” In addition, her plate was overflowing from dealing with her mercurial husband: she was his promoter, cheerleader, and secretary. Her mission became to save Jackson from Jackson. With his oversize ego and gargantuan neediness, Jackson sucked all the air from their farmhouse. How different life would have been had Lee married William Stein.

By 1954 Jackson had begun to drink more and more, paint less and less. Compounding the Krasner-Pollock marriage, physical adultery morphed into an emotional one when he fell for the twenty-six-year-old Ruth Kligman, who saw herself as the Jersey-Jewish Elizabeth Taylor. After catching them together, Lee sailed for Europe. On August 11, 1956, Jackson possessed enough self-awareness to defend his wife to his mistress with the admission, “I’d be dead without her.” Highly intoxicated, that evening Jackson crashed his Oldsmobile into an oak tree on Firestone Place Road. The forty-four-year-old Jackson and Ruth’s friend Edith Metzger died at the scene; an injured Ruth survived. Capitalizing on their relationship, she published Love Affair: A Memoir of Jackson Pollock. Lee remarked that the book should have been called, “My Five F**** with Jackson Pollock—because that’s all there were!” A big-game hunter of artists, Ruth went on to have an affair with Willem de Kooning. Willem said of Ruth, “She really puts the lead in my pencil.” Upon hearing of her husband’s death, Lee returned from France and found Ruth’s clothes in her closet, her painting Prophecy turned against a wall. Although she never got over the loss of her great, flawed husband, she returned to painting. Her room of her own was the barn studio where she came into her own as an artist, a time when she was not merely Mrs. Jackson Pollock. Lee said, “I painted before Pollock, during Pollock, after Pollock.” She never remarried and remained the dragon at the gate of the Pollock legacy. As she had once been dismissed as the great artist’s wife, she fought against being viewed as the great artist’s widow.

The Pollock-Krasner House

To visit the clapboard house in the Springs is to be transported into a home that encompasses a love story, the history of a Goliath of modern art, a midcentury artist’s retreat. Lee Krasner Pollock’s will led to the creation of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. The property is under the jurisdiction of the Stony Brook Foundation, a private, non-profit affiliate of Stony Brook University. The Pollock-Krasner house and Study Center Although initially a weather-beaten farmhouse, Jackson and Lee gave their house a face-lift so that it resembled a white-walled, Manhattan loft. The home, where it is 1948 forever, is so homey one can almost smell the scent of Jackson’s apple pies; he was a mean baker. The kitchen displays a pair of greasy oven gloves hanging on a hook. Above the refrigerator are china pots decorated with whimsical windmills, which held sugar, rice, pepper, and cloves. The windowsill displayed the couple’s garden tomatoes, waiting to ripen. Hanging over a kitchen cupboard is Pollock’s painting Untitled (Composition with Red Arc and Horses.) The image appears to be a ritual scene, possibly a sacrifice. The back of the canvass bears jackson’s signature and his address 46 East 8th Street.The phonograph conjures the image of a needle rotating on vinyl, the echo of jazz drowning out the wind. White shelves hold their extensive books. A fascinating piece is a rusty anchor the couple found on the beach and utilized as a walk decor. Lee’s bedroom window retains her shell collection, the bed holds her plum-colored silk robe, and a rack displays her necklaces. By the mirror is a white sleeveless dress with a silver pattern. On the bedside table is a white rotary phone, vintage radio, jumble of pills, sewing kit, and a pack of cigarettes. Lee’s portrait, sketched by her college boyfriend, gazes upon her former domain. Two vintage suitcases, one printed with the letters J.P. and the other with L.K., souvenirs of husband wife travels, before Lilith-liquor and other women-encroached on their Eden.

While the holy grail of the Vatican is the Sistine Chapel, the sacred relic of The Pollock- Krasner House is the floor on which visitors can only walk with fabric booties, which still allow for the feel of congealed paint. After Jackson became an art world icon, the artist winterized the studio, and covered his floor with pressed wood squares. After Lee’s passing, when the Foundation undertook renovations, workers unearthed the original flooring that preserved the artist’s footprints on its paint-spattered surface. The discovery was a visual diary of Jackson at the peak of his creativity, and one can see remnants of Jackson’s most famous poured paintings: “Autumn Rhythm: Number 30” (the property of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), and “Lavender Mist: Number 1,” (National Gallery, Washington D.C.). Walking on the sacred graffiti, one can summon Jackson crouched over his canvass, wearing a black T-shirt, cigarette dangling from his mouth. Standing on the perimeter, Lee watched her husband with a mixture of love and loathing. Off to the side are her weathered boots.

The final resting place of the couple is in Springs’ Green River Cemetery. Their headstones are made of locally quarried granite; Lee’s is substantially smaller.

Perhaps Jackson’s final bender occurred because he felt he had lost his Lenore, a sentiment echoed in the closing line of “The Raven,” where Poe wrote, “And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor / Shall be lifted-nevermore.”

A View from Her Window

The view was of the Accabonac Creek where blue heron waded.

Nearby Attraction: Grey Gardens

The 1897 property became infamous as the residence of Little Edie and her mother, Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale, the first cousin and aunt of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

If anyone did not seem destined to make her mark in the avant-garde art world, it was the Brooklyn-born Lena Krasner, one of seven children. Her parents were Orthodox Jews from a Russian shtetl who had fled after the 1903 Kishinev pogrom. She changed her name from Lena to Lenore because of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven,” which portrays a man tormented by the loss of his beloved. Poe described the man’s angst: “Vainly I had sought to borrow / From my books surcease of sorrow-sorrow for the lost Lenore”. The rebel settled on the American, androgynous Lee, and removed an ‘s’ from her surname. Family drama transpired when Rose, her older sister, died, leaving her husband, William Stein, and two young daughters. In keeping with Jewish tradition, as the next oldest daughter, her parents expected Lee to marry William, a movie-projector operator. Upon her refusal, the responsibly fell to her sixteen-year-old sister, Ruth. As a result, the siblings’ relationship suffered.

The Girls High School expelled Lee for refusing to sing religious Christmas carols, something she objected to as a Jew. At age thirteen, Lee attended Washington Irving High, the only school in New York to permit females in art classes. Postgraduation, she enrolled in the National Academy of Design which she described as a place of “congealed mediocrity.” During the Great Depression, Lee painted murals for the WPA artists’ project where she met Willem de Kooning. A scholarship allowed her to study with Hans Hofmann, a German émigré abstract expressionist painter who had known Matisse, Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Picasso. He commented on her canvas, “This is so good, you would never know it was done by a woman.” Until he ended the relationship, Lee lived with a Russian art student, Igor Pantuhoff.

In 1940 Manhattan’s McMillen Gallery was putting on an exhibit featuring Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Georges Braque, and invited an equal number of unknown American artists: Willem de Kooning, Paul Jackson Pollock, and Lee Krasner. As Jackson lived a block away, Lee dropped by, although Willem had described Jackson as looking like “some guy who works at a service station pumping gas.” She recognized him as the man she had met four years earlier at an Artists’ Union loft party and had refused to go out with him because he was a “lousy dancer.” Then she saw his paintings and recalled, “I almost died.” Falling for the artist as well as his art, lousy dancing no longer mattered. Lee moved in.

Weeks after V-J Day, after they were married in Marbel Collegiate Church in Manhattan, they visited Springs, East Hampton, Long Island, and swooned under its spell. For five thousand dollars they purchased a nineteenth-century farmhouse on the Accabonac Creek, replete with a barn and five acres. Heiress Peggy Guggenheim provided the two thousand-dollar down payment; she adored Jackson, though she never cared for Lee. Peggy was equipped with a sex drive as huge as a Pollock canvass. She tried to seduce Jackson, but he later remarked, “You would have to put a towel over Peggy Guggenheim’s head to have sex with her.” Other men were not as discerning. When asked by an interviewer how many husbands she had, Peggy replied, “Mine or other people’s?” The home lacked heat, hot water, and an indoor bathroom, but it provided—if not Poe’s raven—a crow they named Caw-Caw. In their isolated sanctuary, the couple dug for clams, rode their bikes to the beach (they did not own a car), and painted. A Hampton Mother Hubbard, Jackson traded art for food with the proprietor of the nearby Springs General Store; it displays a reproduction of the Pollock painting that the store obtained in the deal of deals. Local lore holds that the Jackson Pollock canvass sat behind the couch of the store’s owner for years as he did not know what to make of the paint-splashed painting. Lee harbored the hope their rural retreat would distance her husband from the siren call of the Greenwich Village bars. As the first of the post–World War II artists to settle in the Hamptons, the Pollocks were the founders of its legendary art colony.

Initially Jackson painted in their bedroom; however, requiring more space, he turned their barn into his studio whose open space allowed him to lay a giant canvas on the floor, resulting in his breakthrough “drip method.” Life magazine declared Pollock was the greatest living artist in the U.S. During their hungry days, they would have been astounded that a Lee Krasner painting would be sold for $11.6 million, a Jackson Pollock for $200 million.

The paradigm in their marriage was while he was the one with the fame, she was the watchdog of his reputation. She recalled, “There were the artists and then there were the ‘dames.’ I was considered a ‘dame’ even if I was a painter too.”

As Jackson’s success skyrocketed, he proved he was not only adept with his paintbrush. When Lee learned of her husband’s infidelity, she again, though in a different way—felt “I wanted to die.” While intoxicated, he could also make her the target of his verbal grenades: “Imagine being married to that face.” Deeply hurt at his cruelty, womanizing, and drinking, Lee commuted to Manhattan to consult with her psychiatrist. Still, she sacrificed at his alter and only denied him a child. As she explained, she “married him to become an artist, not a mother.” In addition, her plate was overflowing from dealing with her mercurial husband: she was his promoter, cheerleader, and secretary. Her mission became to save Jackson from Jackson. With his oversize ego and gargantuan neediness, Jackson sucked all the air from their farmhouse. How different life would have been had Lee married William Stein.

By 1954 Jackson had begun to drink more and more, paint less and less. Compounding the Krasner-Pollock marriage, physical adultery morphed into an emotional one when he fell for the twenty-six-year-old Ruth Kligman, who saw herself as the Jersey-Jewish Elizabeth Taylor. After catching them together, Lee sailed for Europe. On August 11, 1956, Jackson possessed enough self-awareness to defend his wife to his mistress with the admission, “I’d be dead without her.” Highly intoxicated, that evening Jackson crashed his Oldsmobile into an oak tree on Firestone Place Road. The forty-four-year-old Jackson and Ruth’s friend Edith Metzger died at the scene; an injured Ruth survived. Capitalizing on their relationship, she published Love Affair: A Memoir of Jackson Pollock. Lee remarked that the book should have been called, “My Five F**** with Jackson Pollock—because that’s all there were!” A big-game hunter of artists, Ruth went on to have an affair with Willem de Kooning. Willem said of Ruth, “She really puts the lead in my pencil.” Upon hearing of her husband’s death, Lee returned from France and found Ruth’s clothes in her closet, her painting Prophecy turned against a wall. Although she never got over the loss of her great, flawed husband, she returned to painting. Her room of her own was the barn studio where she came into her own as an artist, a time when she was not merely Mrs. Jackson Pollock. Lee said, “I painted before Pollock, during Pollock, after Pollock.” She never remarried and remained the dragon at the gate of the Pollock legacy. As she had once been dismissed as the great artist’s wife, she fought against being viewed as the great artist’s widow.

The Pollock-Krasner House

To visit the clapboard house in the Springs is to be transported into a home that encompasses a love story, the history of a Goliath of modern art, a midcentury artist’s retreat. Lee Krasner Pollock’s will led to the creation of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. The property is under the jurisdiction of the Stony Brook Foundation, a private, non-profit affiliate of Stony Brook University. The Pollock-Krasner house and Study Center Although initially a weather-beaten farmhouse, Jackson and Lee gave their house a face-lift so that it resembled a white-walled, Manhattan loft. The home, where it is 1948 forever, is so homey one can almost smell the scent of Jackson’s apple pies; he was a mean baker. The kitchen displays a pair of greasy oven gloves hanging on a hook. Above the refrigerator are china pots decorated with whimsical windmills, which held sugar, rice, pepper, and cloves. The windowsill displayed the couple’s garden tomatoes, waiting to ripen. Hanging over a kitchen cupboard is Pollock’s painting Untitled (Composition with Red Arc and Horses.) The image appears to be a ritual scene, possibly a sacrifice. The back of the canvass bears jackson’s signature and his address 46 East 8th Street.The phonograph conjures the image of a needle rotating on vinyl, the echo of jazz drowning out the wind. White shelves hold their extensive books. A fascinating piece is a rusty anchor the couple found on the beach and utilized as a walk decor. Lee’s bedroom window retains her shell collection, the bed holds her plum-colored silk robe, and a rack displays her necklaces. By the mirror is a white sleeveless dress with a silver pattern. On the bedside table is a white rotary phone, vintage radio, jumble of pills, sewing kit, and a pack of cigarettes. Lee’s portrait, sketched by her college boyfriend, gazes upon her former domain. Two vintage suitcases, one printed with the letters J.P. and the other with L.K., souvenirs of husband wife travels, before Lilith-liquor and other women-encroached on their Eden.

While the holy grail of the Vatican is the Sistine Chapel, the sacred relic of The Pollock- Krasner House is the floor on which visitors can only walk with fabric booties, which still allow for the feel of congealed paint. After Jackson became an art world icon, the artist winterized the studio, and covered his floor with pressed wood squares. After Lee’s passing, when the Foundation undertook renovations, workers unearthed the original flooring that preserved the artist’s footprints on its paint-spattered surface. The discovery was a visual diary of Jackson at the peak of his creativity, and one can see remnants of Jackson’s most famous poured paintings: “Autumn Rhythm: Number 30” (the property of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), and “Lavender Mist: Number 1,” (National Gallery, Washington D.C.). Walking on the sacred graffiti, one can summon Jackson crouched over his canvass, wearing a black T-shirt, cigarette dangling from his mouth. Standing on the perimeter, Lee watched her husband with a mixture of love and loathing. Off to the side are her weathered boots.

The final resting place of the couple is in Springs’ Green River Cemetery. Their headstones are made of locally quarried granite; Lee’s is substantially smaller.

Perhaps Jackson’s final bender occurred because he felt he had lost his Lenore, a sentiment echoed in the closing line of “The Raven,” where Poe wrote, “And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor / Shall be lifted-nevermore.”

A View from Her Window

The view was of the Accabonac Creek where blue heron waded.

Nearby Attraction: Grey Gardens

The 1897 property became infamous as the residence of Little Edie and her mother, Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale, the first cousin and aunt of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.