Mother Courage (1920)

“We are coming down from our pedestals and up from the laundry room.”

No domestic goddess of today could hold a candle to the 1950s Happy Days sitcom mom, Mrs. Cunningham, whose advice could slay any crisis. She would have been appalled with the 1980s Roseanne Barr who boasted, “As a housewife, I feel that if the kids are still alive when my husband gets home from work, then hey, I’ve done my job.” Bella Abzug was more Roseanne than Mrs. C. as she blazed a fiery trail.

Émile Zola once gave his reason for living as, “I came to live out loud.” Bella could have amended his sentiment to, “I came to live out louder.” The activist with chutzpah started life as Bella Savitzky from the Bronx, the younger sister of Helene, to Jewish immigrants from Russia. Her father, Emmanuel, who his daughter later described as a “humanist butcher,” owned the Live and Let Live Meat Market on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. For Bella, a cherished childhood memory was attending synagogue with her grandfather, Wolf Tanklefsky, though she chafed that women had to sit behind a curtain to separate them from the men. Levi Soshuk, her Hebrew schoolteacher, recruited her to a Zionist group that raised money for a Jewish homeland. Her first speech, at age twelve, was in a New York subway where she solicited donations.

Her father’s passing when she was thirteen planted the seed from which sprung her fiery feminism. Her earliest act of rebellion concerned the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, a ritual reserved for males. In her autobiography, Bella on Bella, she wrote, “In retrospect, I describe that as one of the early blows for the liberation of Jewish women. But in fact, no one could have stopped me from performing the duty traditionally reserved for a son, from honoring the man who had taught me to love peace, who had educated me in Jewish values. So it was lucky that no one ever tried.” Her advice, “Be bold, be brazen.”

After Hunter College, where Bella was the student body president, adroit at the art of the argument, she set her sights on becoming a lawyer, her childhood aspiration. Outraged that Harvard rejected her on the basis of her sex, she enrolled in Columbia University on a scholarship, and she became the editor of the Law Review. During this time, she discovered two passions: poker and romance. While visiting relatives in Miami, she met fellow New Yorker Martin Abzug on a bus, also headed for a Yehudi Menuhin concert for Russian War Relief. Although they shared a love of music, while politics was an essential part of Bella’s DNA, Martin was apolitical. Despite their differences, marriage followed after Martin assured her she could pursue her career despite the societal stigma against working mothers. They moved to a house in Mount Vernon, New York, where they raised daughters, Liz and Eve. Nanny Alice Williams helped with the girls as Bella’s duties pulled her in several directions away from home. Bella received her degree in 1947; two percent of the graduates were women.

In private practice after World War II, Bella fought for the defense of the defenseless, such as victims of Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch-hunts; she also drafted legislation for the 1954 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. A rebel with many causes, she led demonstrations in Washington on behalf of nuclear test bans.

A case that garnered international coverage was her defense of Willie McGee, a young, black man from Mississippi who an all-white jury sentenced to death after deliberating less than three minutes for the rape of a white woman. White supremacist groups reacted with hostility to the Jewish, female lawyer from the North. The hotel where she had planned to stay refused her accommodation. Bella, eight months pregnant, spent the night on a bench in a bus station. Local newspapers wrote of lynching McGee and his “white, lady lawyer.” She pursued the case through two appeals and numerous death threats before Willie’s life ended in the electric chair. Martin said of his wife, “That woman has more guts than the whole damn Army.”

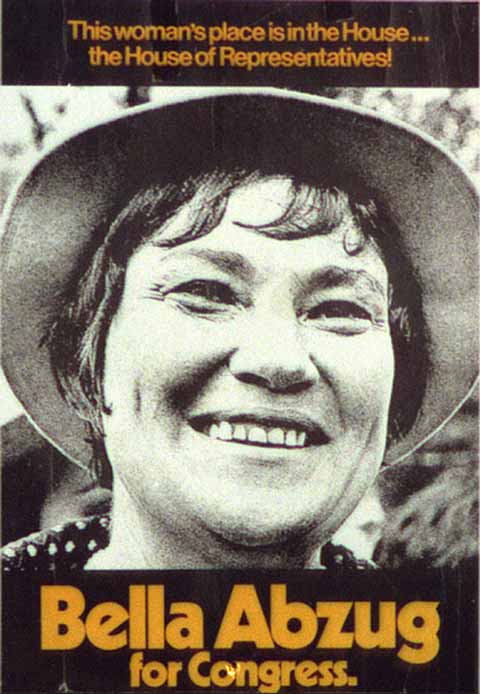

At age fifty, Bella stepped into national prominence when she became the first Jewish Congress woman. There were only ten female U.S. representatives at the time, and she canvassed with the slogan, “This woman belongs in the House.” The rank sexism of the system manifested itself when New York Mayor John Lindsay, asked by a TV reporter why there were so few women in his administration, replied, “Honey, whatever women do, they do best after dark.” In that era, men felt no compunction to make fun of a woman’s looks, and Bella’s weight served as a target. The all-male New York press club Inner Circle featured a well-padded Abzug impersonator in its 1971 show, who danced around singing, “I guess I’ve never been the high-fashioned kind/Mother Nature gave me a big behind.”

Her headquarters located next to the Lion’s Head, a writer’s bar in Greenwich Village, doubled as a day-care center for her legions of female volunteers. Nevertheless, her wrecking-ball persona proved an irritant. A campaign worker repaired to the Lion’s Head one night, clutching his side, swearing never to work for Abzug again as she had punched him during a quarrel over scheduling. The next day, Bella proved contrite, “Michael, I called to apologize. How’s your kidney?” Abzug became one of the most outspoken members of Congress that earned her the moniker “Battling Bella.” She denounced her white, male colleagues, arguing they were part of a privileged elite and were out of touch with America. Upon her election, Abzug fought against sex discrimination, and she introduced the first gay rights bill.

When people used derogative adjectives against Representative Abzug, she responded that if she had been a man they would have substituted the word abrasive for courageous, strident for forceful. In her autobiography, Bella! Ms. Azburg Goes to Washington, she wrote, “There are those who say I’m impatient, impetuous, uppity, rude, profane, brash and overbearing. Whether I’m any of these things, or all of them, you can decide for yourself. But whatever I am-I am a very serious woman.”

The desire to be taken seriously was behind Bella’s trademark floppy hats which she initially wore so clients would realize she was the attorney, not a secretary. Soon she was collecting hats the way Imelda Marcos would later collect shoes. The fashion statement made her easily recognizable, especially in contrast to the fourteen women in the 435 male House dressed as conservatively as possible so as to not draw attention. Moreover, her booming Bronx voice was a foghorn that writer Arthur Miller stated, “could boil the fat off a taxicab driver’s neck.” Truck-drivers and construction workers needed no translation of her oft used invectives. She upped her style when her purple hat matched her purple suit, a gold brimmed number coordinated with a gold-checked suit. When she became a member of Congress, she realized fellow politicians disapproved of her flamboyant fashion, which cemented her choice of apparel. The chapeaus became a foil for comediennes; one quipped that one day Abzug threw one into the air, and it landed on Carl Albert, completely covering the pint-sized Representative from Oklahoma. The only man who was able to compel her to go bareheaded: William “Fishbait” Miller, who made the demand when Abzug was about to step out on the House floor for the first time. She told him to perform an impossible sex act, but she removed the offending hat.

She badgered President Nixon as well; a visit to the White House prompted her to write in her journal, “Who wants to listen to his pious idiocies?” In the receiving line, she announced to the Chief Executive that her constituents demanded a withdrawal from Vietnam. At a later date, she employed a procedural tactic to force the Nixon administration to surrender the Pentagon Papers and was the first member of Congress to call for impeachment. Gerald Ford, in hot water for his pardon of Nixon, agreed to testify before a congressional committee as long as there was a time limit “and no questions from Bella Abzug.” In 1975, a Gallup poll announced she was one of the twenty most influential women in the world. So prominent had Bella from the Bronx become that in 1977 Andy Warhol was on his way to paint a portrait of Abzug for Rolling Stone that would celebrate her run for the mayor of New York. After Elvis died, the magazine postponed the cover until a future edition at which time she had lost her bid.

Bella never stopped jousting. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter fired her from a voluntary position on a Labor Department advisory committee on women after she criticized his decision to cut funding for women’s programs. The majority of the committee’s members resigned in solidarity. She tossed off her dismissal, “I’ve got to find myself another big, nonpaying job.” In 1996, she campaigned for Clinton’s reelection “because the Republicans are advancing a pre-fascist state.” As one who did not care about treading on toes, she collected enemies as other women did charms on a bracelet. In the mountains of hate mail she regularly received, one Democrat wrote, “You have made a Republican out of me.” Fellow feminist Betty Friedan threatened to throw a plate of spaghetti at Abzug who was wearing a white suit. Frances Cash, a former secretary told the Washington Post, quit to become a flagman on a construction site as she figured it was easier on her nerves than “listening to Bella screaming.” Former President George Bush, on a private visit to China that coincided with the Beijing Conference where Abzug was a speaker, addressed a meeting of food production executives, “I feel somewhat sorry for the Chinese, having Bella Abzug running around. Bella Abzug is one who has always represented the extremes of the women’s movement.” Upon hearing Bush’s remark, Ms. Abzug, 75 and in a wheelchair, retorted, “He was addressing a fertilizer group? That’s appropriate.”

In contrast, her husband, Martin, was always in Camp Bella, and weekends were reserved for him. Naturally, being married to a force of nature was to undergo an existence of shock-and-awe. Bella, empathetic to the gay cause, especially after her daughter Liz came out as a lesbian, locked horns with Baptist singer Anita Bryant who fought to repeal homosexual nondiscrimination laws. In response, a crowd of 400 gay men held a candle-lit vigil outside the Abzug home.

During Bella’s last campaign in 1986, for a house seat in Westchester County, Martin passed away after forty-two years of conjugal devotion. Nine years later she admitted, “I haven’t been entirely the same since.” Her pain was apparent in an article she wrote in his tribute entitled, “Martin, What Should I Do Now?” During the next decade, Ms. Abzug suffered from ill-health, including breast cancer, but she continued to practice law and to work for women.

Bella said she was born yelling and countless realms of ink were employed in describing the force of nature. The most apt of the adjectives: Mother Courage.